The man behind the throne

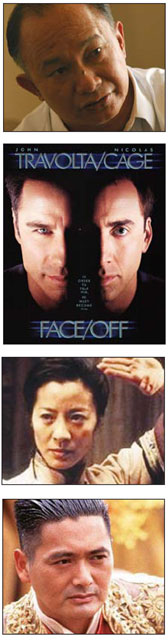

| Producer Terrence Chang has helped Chinese filmmakers enter Hollywood, such as John Woo (pictured below), director of Face/Off; and Hong Kong performers Michelle Yeoh and Chow Yun-fat. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

Movie

Terrence Chang is often known as "John Woo's producer" because he helped his old friend create Face/Off, Mission: Impossible 2 and the extravagant Red Cliff - but Chang is more than that.

Few individuals have expended so much effort as the 63-year-old to promote Chinese filmmakers overseas.

Before Woo sold his house and became the first Hong Kong director to direct Hollywood movies in 1993, Chang enabled Chow Yun-fat to find a US audience.

In 1991, Chang initiated a six-film retrospective of Chow's work in Chicago, Boston, New York and London.

The star of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was a household name in Hong Kong at that time, but he did not think he would have an audience in the United States, besides old people in the country's Chinatowns.

But Chang was more confident: "Chow was in his 30s, in his prime. I was determined to show American audiences that in Asia we also have good, versatile actors."

Thanks to his years at New York University's film school and many Hong Kong studios, Chang managed to invite journalists, critics and producers to the screening.

The smart initiative opened a door for Chow to enter Hollywood, where he starred in three films and later in the smash hit Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon by Ang Lee.

Chang was also behind Michelle Yeoh, the actress who played Aung San Suu Kyi in The Lady, when she started her Hollywood career.

Chang introduced Yeoh to producers of the James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies, who were "so impressed by how fun and smart she was" that they changed a male character into a female role for her.

"If you think Yeoh is as depressed as Yu Xiulian, her role in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, you are making a huge mistake," Chang says, laughing. "She is so energetic and fun. I always think she should do comedy."

To Chang's disappointment, both Chow and Yeoh did not further burnish their Hollywood careers despite promising beginnings.

Chow's English was not good enough, so he was offered mainly action films, but the genre is not his favorite or what he is good at. The best role he got in Hollywood, Chang believes, was the Thai emperor in Anna and the King, who does not have to speak perfect English and has an engaging personal story.

Yeoh speaks fluent English and got great offers, such as the role of Seraph in two sequels to The Matrix. But according to Chang, she refused all of them to protect her relationship with her boyfriend at that time.

"Asian actors are often stereotyped as just kungfu stars," Chang says. "But sometimes personal reasons, timing and luck matter, too."

Chang's most successful Hollywood adventure is his collaboration with John Woo, his buddy for 30 years.

In 1992, Woo had built his name through the "balletic violence" in films, such as A Better Tomorrow and The Killer, and in one week he would be offered 50 follow-up projects along the same lines. Instead, he wanted to try something new, such as a more Western approach to directing.

Chang found Woo an English teacher before they set off to Hollywood. For six months, Woo studied English for two hours a day, six days a week.

"He is the most hardworking director I have met," Chang says.

But English was not the only thing Woo had to learn. Prominent as he is in Asia, he was just another newcomer in Hollywood.

When directing Hard Target in 1993, he had no final say over the script and editing.

His clout as a director, according to Chang, was built gradually. The 1997 hit Face/Off, starring John Travolta and Nicolas Cage, was a turning point.

Woo wanted Travolta's role to adopt Cage's son at the end, but this was rejected, because the studio thought a hero shouldn't adopt a villain's child. In the test screenings, however, most viewers asked why Travolta did not adopt the boy. Finally, the studio kept Woo's ending for the final version.

After Face/Off, Woo had a mainstream commercial base in the US and had the final say over the script, casting and editing. However, Chang says he was never really into the country and its culture.

"He watched Chinese TV shows at his New York house," Chang says.

He was offered many scripts, but most were along the lines of Mission: Impossible or Face/Off. He didn't want to repeat himself.

Additionally, he was tired of the managerial and editorial concerns of major studios.

"Studio employees may have studied accounting or law at university, rather than movie making, but they wanted to have a say in order to justify the money they were earning," Chang says.

At the same time, Woo found such directors as Zhang Yimou and Ang Lee were making Chinese stories. He could not wait any longer to direct a Chinese story that had obsessed him for years - the tale of Three Kingdoms (AD 220-280).

Woo wanted to interpret the story in his own way, describing the brotherly love among heroes in a chaotic time. He tried to persuade Chang to go back to China to find investors.

But Chang did not like the story. He believes it is fake, because in reality they actually tried to kill one another.

Woo, however, knew how to get around his friend and invited him and another pal, who he asked to become his producer, to dinner.

"He tried to irritate me, because everyone knows I am his producer, there cannot be anyone else. I decided to do it anyway."

Chang flew to Beijing, where he "literally knew no one". He was frustrated until a friend introduced him to Dong Ping, CEO of Beijing Poly-huayi Media. Dong loves the Three Kingdoms' story and wanted to invest in the film.

Their efforts resulted in the war epic Red Cliff, the most expensive Chinese film then at $80 million, including $1 million of Woo's own money.

The film's two installments grossed $100 million domestically, but when released in North America as one film, it raked in just $620,000.

"Like it or not, kungfu is still the safest genre for Chinese cinema in terms of global distribution," Chang says. "So far, the highest-grossing Chinese films in North America are Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero."

The duo will not play the safe card next time, however. In March they will start filming a "Chinese Titanic", a love story set in 1949, the year Chang was born and the People's Republic of China was founded.

Based on a real incident, the story revolves around a ship called Taiping, which collided with another ship and sank shortly after it left Shanghai for Taiwan. Thousands of passengers lost their lives.

It will be a "love story of Chinese people", Chang says. Zhang Ziyi will be onboard.

Another blockbuster they are planning is about the Flying Tigers, the Chinese and US fighter pilots during World War II.

Chang does not agree with Woo on everything. He and another writer finished the script of the 1949 story and Woo is rewriting it for the 15th time.

And, as a producer, he actually prefers the Hollywood system, which makes it clear who will do what for how long and with how much money every day, while on the mainland and in Hong Kong, things are more flexible but can be more chaotic.

But they have worked shoulder-to-shoulder for decades in Hong Kong, Hollywood and Beijing.

"He is a good director. Otherwise, I wouldn't stay," Chang says.

China Daily