For Kwok brothers, it appears mum knows best

Mother knows best when it comes to running the world's second-largest real estate company.

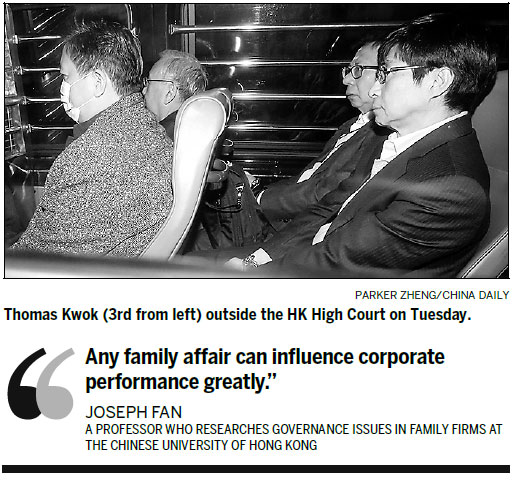

That's one conclusion from the graft trial of Hong Kong's billionaire Kwok brothers, which ended on Tuesday with Thomas Kwok jailed for five years for corrupting Rafael Hui, the city's chief secretary from 2005 to 2007. His younger brother Raymond Kwok, who was also a defendant in the case, was acquitted of all charges.

Thomas and Raymond wrested control of developer Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd from their eldest brother Walter in 2008 after their mother intervened, according to testimony heard in the trial which started seven months ago.

Even though the matriarch, Kwong Siu-hing, did not hold a position in the firm at the time of Walter's ouster, she called the shots by controlling the trust that holds the family's stake in the $42 billion company. Kwong, now 86, stepped in to lead the company's board in 2008 and stripped Walter from the family trust in 2010 before ceding chairmanship to her two younger sons in 2011.

The family had kept private that Walter had been acting erratically since he was kidnapped by a gangster in 1997, testimony revealed. His troubles were only disclosed to shareholders more than a decade later when he stepped back from running the company.

"Any family affair can influence corporate performance greatly," said Joseph Fan, a professor who researches governance issues in family firms at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. "Many Chinese families do not have family governance mechanisms in place, including the Kwok family."

The case speaks to broader corporate governance issues in Hong Kong, where family businesses dominate the economy. The six wealthiest men and their families build the majority of properties, dominate telecommunications and control bus routes and port access.

The court heard how Hui was hired as a HK$15 million ($1.94 million)-a-year adviser to Sun Hung Kai under a secret agreement, and how payments were hidden and salaries routed via personal bank accounts and intermediaries. At times, it appeared as if the conglomerate was run more like a mom-and-pop operation than the listed property giant it is.

"It just underlines it's a family company even though it's a big one," said David Webb, a Hong Kong-based investor and shareholder activist. "There's always some investment risk associated with the profile of owners of companies, whether they're government-controlled or family-controlled."

Sun Hung Kai has won a slew of corporate governance awards. It was named Asia's best-managed company for four straight years in an annual poll conducted by Euromoney magazine and it took the top award last year from Corporate Governance Asia, a Hong Kong-based publication.

"The board sets the company's strategies and ensures good governance, and the executive committee makes all major commercial decisions collectively," Sun Hung Kai said in a response to questions, while declining to comment on the trial. It is committed to the highest levels of governance, it said.

Fiona Wan, a spokeswoman for the Kwok's family trust, declined to comment about Kwong's control of the family fortunes.

Sun Hung Kai said recently the convictions of Thomas Kwok and executive director Thomas Chan have not affected its business and operations. Adam Kwok, Thomas's 31-year-old son, who had been appointed as an alternate director for his father when the latter was charged in 2012, was appointed as an executive director.

Shares rose the most in two and a half months on Tuesday when they resumed trading for the first time since the verdicts.

In cases where family members own a bulk of the company, outside shareholders are sometimes left out of the decisions.

Corporate governance norms are especially hard to attain at sensitive times such as the death of the patriarch or matriarch, and decisions are made behind closed doors, as heard in the trial of the Sun Hung Kai chairmen.

The Kwok family trust has the largest stake in Sun Hung Kai, co-founded in 1963 by the brothers' father, Kwok Tak-seng. Walter took over as chairman after his father's death until he was forced out in 2008 on the grounds of mental illness.

Walter said at the time he didn't have any such disorder and sued his siblings for libel, a case that was later dropped. He alleged that his brothers accused him of making unwise investment decisions and called him a liar, according to a court filing.

The defense of Thomas, 63, and Raymond, 61, against charges of corrupting Hui relied on their brother Walter's emotional and physical health.

Thomas Kwok said he struck an unwritten consultancy agreement with Hui in 2003 for HK$15 million, which was the highest ever paid to an adviser by the company. He testified the deal was concealed because Thomas promised his mother he wouldn't do anything to provoke Walter, who was opposed to hiring Hui at the time.

(China Daily USA 12/25/2014 page16)