Living wills enliven debate about death

A growing number of people believe that quality of life is more important than longevity. Liu Zhihua reports.

Attitudes to death are changing in China. Once, the subject was taboo - the number four, si in Chinese, is still deemed unlucky because it sounds uncomfortably like the word for death - and traditionally, people have been reluctant to discuss the end of life or challenge treatment plans presented by physicians or close relatives.

The situation is now changing, partly because of greater contact with the outside world and partly thanks to the advent of "living wills".

The wills offer people the opportunity to specify how they want to spend their final days, and provide a guarantee that their wishes will be acted upon in the event that illness means they are unable to communicate, consent or disagree.

The wills are not legally binding and the testator is allowed to withdraw the document, but for the first time people are being offered a chance to state the treatment and life-support measures they would be willing to accept as death draws near, ranging from being fed by a tube, to having invasive ventilation, dialysis and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

According to the Beijing Living Will Promotion Association, the first organization on the mainland to provide living wills online, more than 20,000 people have signed up via its website, which has been visited by tens of thousands keen to learn more about the process.

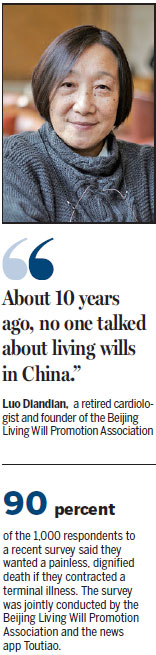

According to Luo Diandian, who founded the association in 2013, the idea is catching on outside the capital, and the association has been contacted by people in Guangzhou and Shenzhen, Guangdong province, and Xi'an, Shaanxi province, who are considering establishing similar projects.

"About 10 years ago, no one talked about living wills in China. When I tried to convince people of the necessity of making one, they immediately thought I was talking about euthanasia (which is illegal in China), and rebuffed any further attempts at conversation," the retired cardiologist said.

"Now, living wills and palliative care are often the topics of government conferences and forums and no matter whether people see the necessity for them or not, at least they know about them."

Maternal influence

In 2013, when Beijing resident Cui Di (not her real name) heard about Luo's website, she didn't hesitate to make a living will. The 60-something retiree said her decision had been influenced by her mother, who died from colorectal cancer.

Although Cui's mother told the family about her illness in January, 2002, she refused to be hospitalized. A few weeks later, during Spring Festival, she asked Cui to take her to the hospital, where she rejected all treatment except pain relief. She died two months later.

"Mother was very insightful. She knew that medical treatment could only delay her death at best, but she would have to live in pain. She was very brave and decided not to cling to such a painful life," Cui said, adding that she and her husband, also a retiree, have decided to refuse life-prolonging measures if they contract a terminal illness.

For Shao Hua, a resident of Nanchang in Jiangxi province, living wills make things easier for families.

The 62-year-old cited the example of her husband, who had a stroke in May. He is now recovering, despite complications, including loss of speech. However, if his condition had been more acute, Shao would have struggled to decide whether to abandon life-support measures, despite the fact that she and her husband had already agreed that living in vegetative state would be worse than death.

"If he had been brain dead, I would have allowed him to die with dignity, rather than feeding him via a tube, but I could never be 100 percent sure that he would have agreed with my decision. If he had made a living will, I would have known his thoughts," she said.

Shao has now made her own living will, and will discuss the matter with her husband when his condition has improved further.

Painless and dignified

The results of a survey jointly conducted by the association and the news app Toutiao in September showed that 85 percent of the 1,000 respondents believed they were the best person to make important decisions about their treatment. Meanwhile, more than 90 percent said they would want a painless, dignified death in the event of contracting a terminal illness, and about 83 percent said they would make the same decision on behalf of family members.

For Zhang Xiaoxi, a civil servant in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, a peaceful, painless, dignified death would be the most desirable exit from the world. The 50-year-old civil servant, who said she has been contemplating death since the age of 30, made a living will earlier this year, after hearing about the association in Beijing.

There is no comparable organization in Hangzhou, but people in the city are becoming increasingly open-minded about discussing death and living wills, Zhang said.

She noted that a few years ago, a doctor in the city attracted national attention after it emerged that he had allowed his father, who had advanced cancer, to live out the last months of his life quietly in the countryside, instead of insisting on time-consuming, painful chemotherapy in the hospital.

Instead of criticizing the son, most people showed sympathy and understanding, even though his behavior would have been regarded as unfilial in days gone by, she said.

However, the association's Luo said there is still a long way to go before the idea is widely accepted.

She believes that a key step would be for the health authorities to include living wills in patients' official medical records, so their physicians will know exactly what treatment they would be willing to undergo as their life draws to a close.

Quality of life

Song Yuetao, assistant to the president of the Beijing Geriatric Hospital, said people are increasingly aware that quality of life is more important than longevity.

In the past, it was difficult to talk about death with dying patients, and the phrase "living wills" - which translates as "requests before death" in Chinese - was shunned because it sounded ominous.

The hospital's own version of the living will - which allows testators to "reject invasive rescue and treatments" - has been welcomed by patients and their families.

"Chinese people often say that it's better to live in misery than to die, but nowadays people are more prepared to question those traditional ideas," Song said.

Contact the writer at liuzhihua@chinadaily.com.cn

| A patient in the oncology and hematology department of the Beijing Haidian Hospital makes paper lanterns in the company of volunteers from the Beijing Living Will Promotion Association.Ting Ting / For China Daily |

| A patient walks with the help of a wheeled walking frame at the Beijing Songtang Hospice, which offers care services for terminally ill patients.Photos By Zhang Yu / Xinhua |

| An elderly man chats with a nurse at the hospice.Photos By Zhang Yu / Xinhua |

(China Daily USA 11/03/2016 page6)