A century later, city still struggles with slaughter

Five-year-old George Monroe was enveloped by sheer terror.

"All of a sudden my mother was excited because she saw four men coming towards our house. All of them had torches, lighted torches on their side coming straight to our house," recalled Monroe in the mid-1990s. "When these four men came in, they walked right past the bed, straight to the curtains in the house and they set fire to the curtains. As a result, everything in and around was burning."

All the time, Monroe was hiding under the bed with his older sister, who threw her hand over his mouth to stop his screams from being heard when a rioter unknowingly stepped onto his finger.

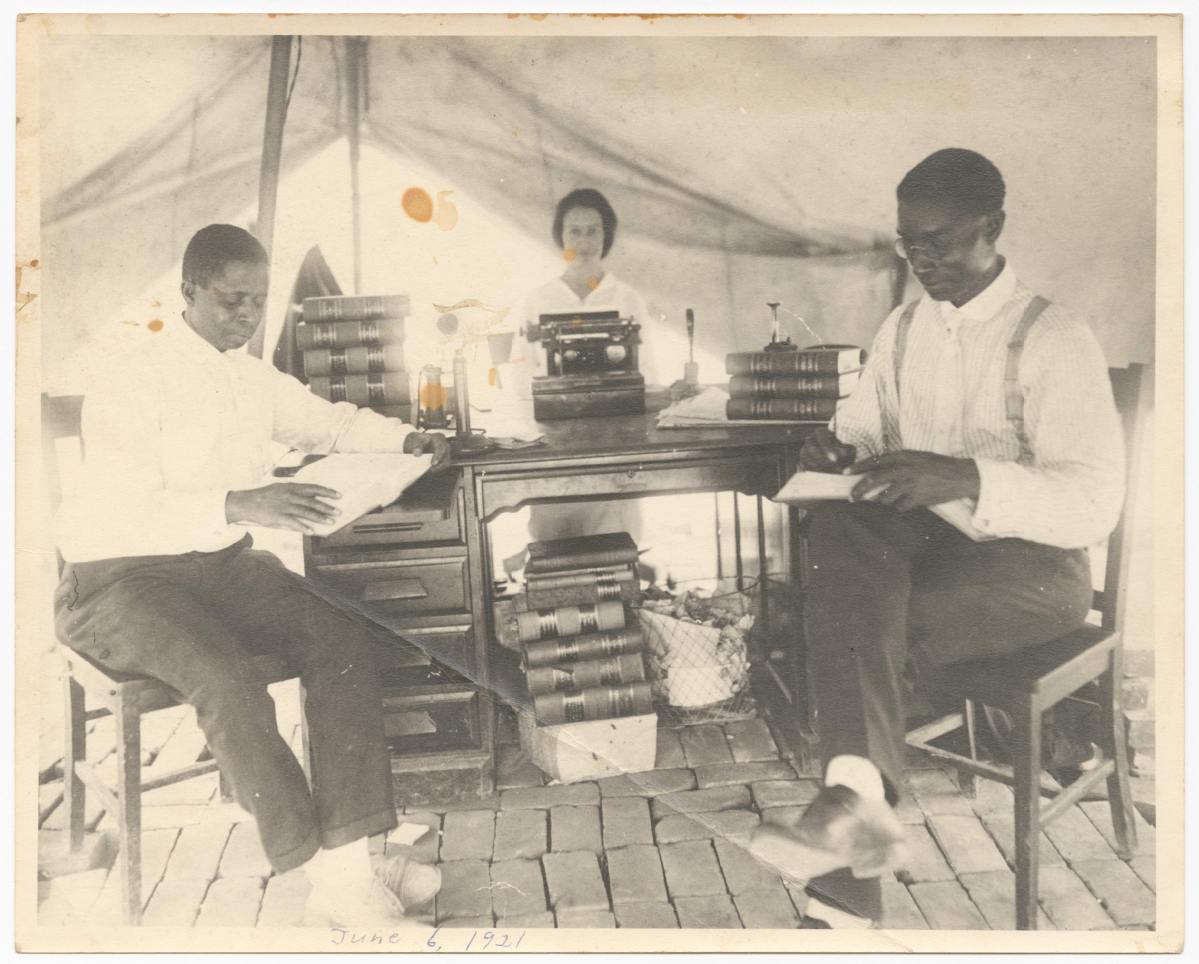

Monroe waited for 75 years to tell his story: in 1996, the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, a state-sanctioned task force, was set up to investigate the massacre, and Monroe was among the 108 survivors whom the commission ultimately located across the country.

Among other things, the commission concluded that the city had conspired with the white mob against its black citizens.

"We don't know of any approved incident where law enforcement officers were murdering people, but what we do know is that they deputized some people in the white mob and provided them with weapons," said Johnson. "The National Guard rounded up black people and put them in internment centers in the middle of the massacre. The stated purpose was to protect them, but we know from the survivors that what it did was to leave the Greenwood community largely defenseless."

However, in a report issued by the Tulsa City Commission two weeks after the massacre, Mayor T.D. Evans was unequivocal: "Let the blame or this negro uprising lie right where it belongs, on those armed negroes and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it."

A lawsuit was filed in September in Oklahoma state court against the City of Tulsa by attorneys for the massacre victims and their descendants, including Fletcher, Ellis and Randle, whose appearance before the congressional subcommittee constitute part of that quest for delayed justice.

In 2007, the US Supreme Court upheld lower court rulings that a federal lawsuit seeking damages was barred by the statute of limitations, effectively telling the victims and their descendants that they were too late for any remedy.

Behind the prolonged fight is what many see as "the greatest conspiracy of silence".

Immediately after the massacre, all original copies of that particular issue of the Tulsa Tribune that instigated the mob disappeared, apparently having been destroyed. The relevant page is even missing from the microfilm copy.

According to a newspaper report at the time, Sarah Page, who left the town immediately after the massacre, later wrote a letter to county prosecutor saying that she didn't want to press charges against Rowland.