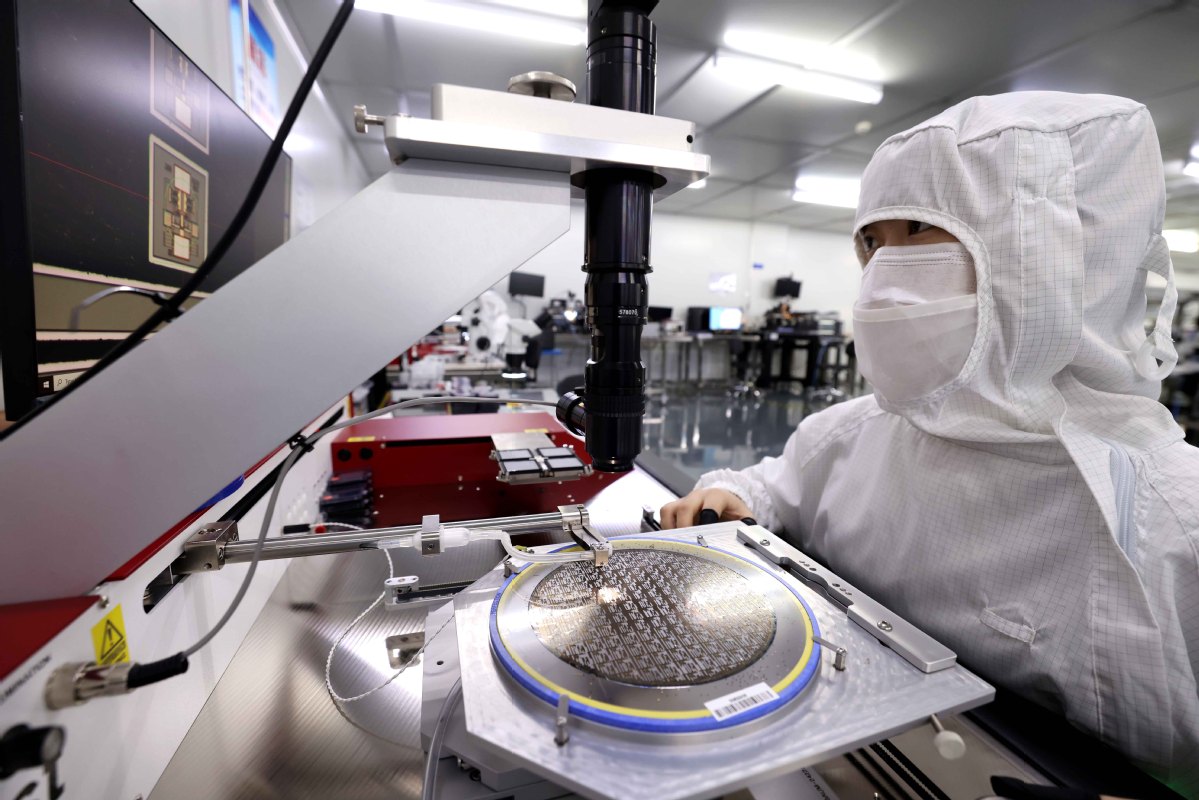

US cannot chip away at China's tech capabilities

By LIA ZHU in San Francisco | China Daily | Updated: 2023-02-08 07:19

Washington's export controls leading to parallel ecosystem, experts say

The United States government's chip export controls to limit China's access to cutting-edge technology is only a temporary hurdle and may eventually enable China to develop its own capabilities, thus weakening the US' domestic competitive advantage, industry experts said.

"There's the objective of us wanting to run faster, and then slowing down China's capabilities.... But in the long term, it might enable China to gain access to those capabilities on its own," Edlyn Levine, chief science officer and co-founder of America's Frontier Fund, said at a recent conference on US-China relations hosted by Asia Society Northern California.

"What you'll end up seeing is (China's) technology development and a parallel ecosystem," she said. Washington's policies on export controls are accelerating this potential parallel ecosystem, she emphasized, adding that the semiconductor industry will end up having fewer benefits from global exchanges.

Last year, the US government announced sweeping export controls, including a measure to cut China off from certain chips made with US equipment, regardless of where they were made.

Washington's policy objective to decelerate China's development certainly works in the short term, as blocking direct access to an advanced technology will slow advance, which is often referred to as a "technology choke point", Levine said.

"My perspective as a scientist is that a technology choke point is a temporal bound. You can undo it if you're sufficiently resourced, and China certainly has put a lot of resources toward its engineers, scientists, tech companies and universities to achieve that," she said.

Using the advanced technology of ultraviolet lithography as an example, Levine said that it might take decades to catch up with such technology, but if adequate resources and talents are involved — and if it is a technology that has been demonstrated before — the export controls are going to be only temporarily limiting.

Kirti Gupta, vice-president and chief economist at Qualcomm, agreed. "The objective is to be able to run faster and it helps in the short term. But in the meantime, the power of the tool (export controls) can also devastate US companies," she said.

" (That is) because foreign competitors can step in to take away the market share, further weakening our domestic competitive advantage. We've seen that again and again in other industries, and also in semiconductors," Gupta added.

Levine said the biggest unintended consequence that the export controls might result in is the impact on US companies from their lack of access to the China market. "If you look at what has happened historically with export controls in the United States, the unintended consequence has been to hurt the market share of the US industry," she said.

A glaring example is the impact of the Export Administration Act of 1979 on the US semiconductor industry. "US capital equipment suppliers — the companies that supply the tools used in fabs (fabrication plants) to make semiconductor equipment — had about a 90 percent global market share at that time," Levine said.

"Ten years later, they had lost about half of their market share, as they were essentially seen as vendors of last resort because of the need to get approvals to sell into foreign markets," she said.

US chipmaking equipment and services company Lam Research Corp has warned of a $2 billion to $2.5 billion revenue hit in 2023 following US export controls on high-end technology to China in October.

Export controls are part of the broader trade policies, including tariffs and subsidies, that the US is using to counter China's development to help boost its own domestic chip manufacturing.

These policies are accelerating a potential rift in the global semiconductor industry, Levine said. "We're facing this acutely now. It is something that is affecting our world in the investment community. It's affecting the corporate world. It's affecting the education research world. All of us are trying to react and to figure out this rather potentially volatile space," she said.