Musical excellence, not 'Chineseness', is key to acceptance

The performance by Chinese classical guitarist Yang Xuefei at Wigmore Hall, London's celebrated classical music venue, turned out to be a very Western experience.

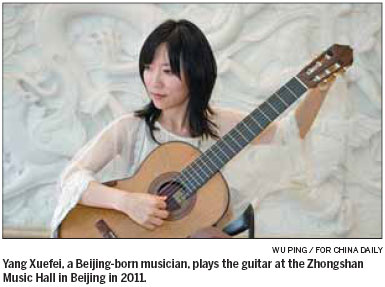

Contrary to my expectations, the 36-year-old Beijing-born musician played only two Chinese-influenced pieces during her 90-minute solo recital on Sunday. The rest of her program consisted of works by Western composers Franz Schubert, Claude Debussy, Benjamin Britten and Manuel de Falla.

Looking around, I noticed that the audience was mainly Western. They looked at the young Chinese woman in awe as she performed music from their own cultural heritage so well on both technical and emotional levels.

They listened in perfect silence, and when Yang finished, they clapped so enthusiastically that Yang had to play two encores.

Surrounded by this passionate applause, I suddenly realized that Chinese artists and musicians can win respect on the international stage by simply excelling at their art and music.

This may sound obvious, but too often our artists and musicians try to be unique by emphasizing their "Chineseness", which can marginalize them in the dominant Western art world.

Take, for example, the Chinese New Year celebration that occurs in London's Trafalgar Square, where Chinese musical instruments, such as the pipa and guqin, an elaborate dragon and lion dance and other sorts of Chinese cultural novelties are ushered onto the stage one after another.

Despite the fact that tens of thousands of members of the British public come to see this spectacular event each year, and despite all the praise British politicians heap on the celebration for adding to the country's "ethnic diversity", I feel that it doesn't help to cultivate a genuine respect for Chinese culture.

It projects an image of Chinese culture as exotic and new, which may attract interest and curiosity, but may not develop either sincere, heartfelt understanding or approval.

Over the years, I have also seen various works by prominent Chinese art groups in the UK, including the performing and visual arts group Chinatown Arts Space and the theater company Yellow Earth. But their works are only appreciated by local Chinese, and go largely unnoticed and unacknowledged by the wider art-loving British public.

I believe one issue with Chinese art in the West is artists' wilful branding of themselves and their work as "Chinese" and "ethnic minority". This may be associated with a need to seek grants from funding organizations such as the UK's Arts Councils, which often earmark funds to promote ethnic minority culture.

But over time, such a "Chinese" label restricts artists' creativity, forcing them to look into their "Chineseness" to such an extent that their artistic expression is contrived, unnatural and highly symbolic.

Instead, Yang's path to success offers an alternative. After graduating with a bachelor's degree in classical guitar in China, Yang came to London's Royal Academy of Music to study. During that time she learned from the world's best musicians and became one herself.

Her passion and hard work on the instrument have transformed her into a serious artist and someone who can leave her legacy on classical guitar music. In doing so, she has become mainstream.

But for Yang, to become mainstream is not at all to forget or hide her "Chineseness".

Indeed, the highlight of Yang's Wigmore concert was the world premiere of Shuo Chang, a piece by Chinese composer Chen Yi, the title of which literally means "speaking and singing". It uses the guitar to imitate the Chinese musical style of combining singing, reciting and drums with a small ensemble.

I asked Yang what made her want to play a Chinese piece when she had already become a respected artist by playing more conventional classical Western music. She replied that she is Chinese and that she wants to do so.

"Playing Chinese-influenced music is a result, but not the purpose," she said. "I want to play Chinese-influenced music, so I play it. I don't do it to make people think I'm unique on purpose. But after I finish playing, people tell me it's unique, and I think that's fine," she added.

Of course, Yang is not the only example of a serious Chinese artist entering the Western mainstream. The legendary cellist Yo-Yo Ma, 57, has received 15 Grammy Awards, and 96-year-old I.M. Pei has been hailed as the "last master of modern architecture".

A younger generation of renowned artists includes pianist Lang Lang, 31, who played at the Queen's Diamond Jubilee in 2012, and singer Gong Linna, 38, who performed at London's Cultural Olympiad that same year.

Common to all is their sincerity and dedication to music, and their courage to be true to their own styles, as opposed to giving in to Western society's expectations of "Chinese art".

As China rises on the world stage as an economic superpower, I believe more respected Chinese artists and musicians will emerge. It is through their work that a Western audience will truly come to respect Chinese art and music as equal, and eventually accept these Chinese art and musical influences into their treasured mainstream culture.

Contact the writer at cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 11/14/2013 page10)