Brazil film records prosperity's clamor

Updated: 2012-08-26 08:00

By Larry Rohter(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

Barking dogs and a crying baby. Maids and housekeepers calling to each other through the air shaft of an apartment building. The echo of samba music on the radio and soccer matches on television. The faint murmur of the sea in the background, and in the foreground, the incessant clatter of construction.

That is the soundtrack of daily life in Brazil's big cities these days, the inevitable accompaniment of an economic boom. But that cacophony also served as inspiration for the director Kleber Mendonca Filho, who decided to give his first feature film, a winner of prizes at festivals in Europe and the United States, the title "Neighboring Sounds."

"We're at a very curious moment right now in Brazil," Mr. Mendonca said. "There's a lot of money, which means building things. And to build things in most cases means demolishing other things, which in turn stimulates my generation of directors and artists to say something about all of that."

"Neighboring Sounds," which opened August 24 in New York with a September release scheduled for the Netherlands, is set in the northern coastal city of Recife, in a middle-class enclave whose newly prospering residents are buying flat-screen televisions and Audis or arranging English and Chinese lessons for their children. But they worry about crime, and when a security firm comes knocking, they eagerly sign on.

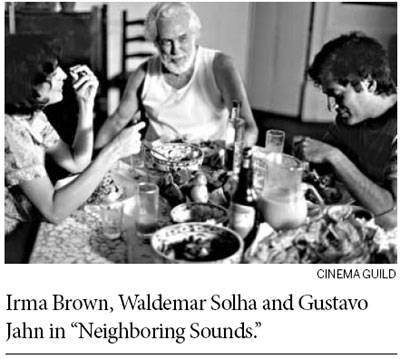

A single family with extensive landholdings dominates the neighborhood, though, and the patriarch, an autocrat named Francisco, played by the novelist and actor Waldemar Solha, doesn't want to cede control.

Mr. Mendonca said that the class tensions that underpin "Neighboring Sounds" came directly from his own job experience. "There we were, in a modern company, with computers and everything, but the mentality that made the place function, the generalized lack of respect, was like that of a plantation owner talking to his cane cutters," he said. "The film comes precisely from this union of the modern and the archaic."

Though "Neighboring Sounds" has a lush, vibrant look, in keeping with its tropical setting, it is in some ways literally a home movie. Not only did Mr. Mendonca shoot most of the scenes on the block where he lives, but one home in the movie is his own apartment.

Mr. Mendonca said that some of the credit for his questioning view of social niceties should go to the film's producer, Emilie Lesclaux, who also happens to be his wife. Ms. Lesclaux, 31, went to Brazil a decade ago to work in the cultural section of the French consulate in Recife, fell in love with Mr. Mendonca and the country at the same time, yet even now finds herself puzzled by some local customs.

"Being with her in ordinary life is really interesting, because she has non-Brazilian reactions to some aspects of Brazilian life, and that make me snap my fingers and say, 'This is interesting,'" he said.

One example, a theme that runs throughout the movie, is the unusually casual and seemingly affectionate relationship between servants, most of whom are black, and their employers, almost all of whom are white.

"When Kleber and I first came together and I met his housekeeper, who had cared for him when he was a child, I was wondering who exactly is this woman and what is their relationship?" Ms. Lesclaux recalled.

Over the last 18 years, Brazil has enjoyed a spurt of growth that has propelled tens of millions of people into the middle class. "Neighboring Sounds" may be the first major Brazilian film that directly deals with that transformation.

From the time of the Cinema Novo movement of the early 1960s, the Brazilian films that were best received abroad have focused on poverty, violence and racism.

Mr. Mendonca said that while he greatly admired Cinema Novo films, the time had arrived for a different approach, since the country has become predominantly middle class.

"Brazilian film has to break the mold," he said, adding that "99 percent of Brazilian filmmakers are middle class or upper middle class or bourgeois, as I am, yet most of the time they're making films about people they don't know that much about and subjects they haven't mastered. We need more films that don't take place in a favela or the backlands and aren't about some guy who is really poor and living beneath a bridge."

The New York Times

(China Daily 08/26/2012 page12)