People's memories of the Olympics quite often

consist of the excitement of athletes competing or standing on podiums accepting

gold medals while their nation's flag is hoisted into the Olympic air. But when

you step into a school deep in a Beijing backstreet, you will discover a

different side of the Olympics.

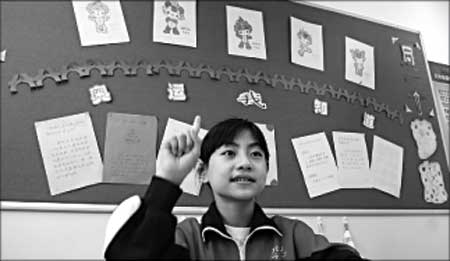

Yang Yuwei, a

11-year-old girl with hearing impairment, expresses "One World, One Dream"

in sign language during an Olympic education course at the Special

Education School of Dongcheng District. [China

Daily]

|

Visitors might find strange the silence in the school. Located in downtown

Beijing, it is home to nearly 200 children aged from four to 18 years old, half

of whom are hard of hearing and the rest are mentally retarded and have

difficulty speaking.

But the youth are by no means locked into a life without sound, and sport is

a major channel for them to learn about the outside world and communicate with

others.

At the gate of the Special Education School in Dongcheng District, there is a

board that marks the countdown to three Games the Summer Olympic Games, the

Paralympic Games and the Special Games.

"Sport is a human right. It can not only help with the physical

rehabilitation of our students, but also teach them how to be real men," said

Headmaster Zhou Ye, who introduced Olympic education into school curriculum in

2003.

The school was named an Olympic Education Model School by the Beijing Olympic

organizers and education authorities in May this year.

"The Olympics is much more than a showcase of athletic excellence," Zhou

said. "The very word also means peace, freedom, equality and progress. And these

are what we want our students to grasp through Olympic education."

The headmaster, an elegant 43-year-old woman, has been teaching

hearing-impaired students for around 20 years. She is also the famous sign

language host of a popular China Central Television (CCTV) news programme,

China's largest television station.

Zhou said children with disabilities usually depend a lot on others. "When

they encounter a difficulty, even a minor one, they know their parents will run

to help them immediately, and that their teachers would also offer a hand

immediately. So the children are prone to give up and wait for help when they

are in trouble. Such a dependent mentality is not good as they grow-up."

But sports can help the disabled build a sense of independence and

self-consciousness, Zhou said. Her school has developed a set of rhythmic

gymnastics, which all the students, including those in wheelchairs, come down to

the playground to perform every day in the morning.

Unlike normal school students, who stand neatly in lines and rows when doing

exercises, the students here are divided messily into different groups. Some can

perform well with the music, including those with hearing impairments; some can

fulfil most part of the gymnastics; some can just do a small part; and some

cannot stand steadily at all.

But all the kids exercise carefully and full of passion. In the last group,

each student is helped by a teacher to stand still and then take a step forward.

Whether they succeed or fail, the teachers will give them warm praise and

encouragement in a way they can understand.

"We want to let the students know that they can make it when they believe,"

Zhou said. "It is a way to let the disabled learn to respect life and respect

themselves. Only when they respect themselves, can they respect others and earn

others' respect. Only when they are mentally independent will they feel the real

freedom and equality that the Olympics brings to them."

Apart from gymnastics, the school has also developed various physical

activities that are suitable for the kids, such as basketball, football, ground

ball and golf.

"I can feel the excitement of the students when they make a good goal. Sports

give them a chance to prove themselves and helps them become more confident,"

Zhou said. "I am always touched by their amazing willpower," she added.

Li Nian, a 10-year-old boy who suffers from brain paralysis, used to not be

able to walk or hold a pencil due to constant convulsions. But he won the gold

medal in the 50-metre race at the Beijing Municipal Special Olympics last year.

"He has kept on doing exercises every day for many years. It is a triumph of the

human spirit," Zhou said.

The special education school also holds its mini-Special Olympics every

spring. "The mentally retarded children are the athletes, and the hearing

impaired students serve as volunteers," Zhou said. "The world of sport

emphasizes rights and freedoms, and it also underlines the concept of

obligations towards others. This is what I want the hearing impaired to learn

from serving as volunteers, and they really did a good job."

Fan Bo, 14, vividly remembered when she helped for her schoolmates in the

mini-Special Olympics early this year. "I accompanied one boy in Class Five,

guiding him to the right place on the playground, and helped him finish

roll-call," Fan said excitedly in sign language. "I knew I was needed, and such

a feeling is terrific."

The school also organizes exchange activities with normal school students.

"We want our students play with their counterparts who are physically-healthy,

and learn how to interact with society," Zhou said.

She recalled an Olympic knowledge contest between her school and a normal

secondary school. "I was much moved to see that our students were even more

active in answering questions than those from the secondary school, and their

answers were correct."

"Integrating Olympic education into our curriculum ensures awareness of the

Olympic movement and spirit and also motivates our youth to participate in the

Olympic experience in any way they can," Zhou said. "I was excited with the

achievements they have made, and each of the students here is our pride."