Long arm of the law grabs its man

By He Na, Zhang Yan and Li Jing (China Daily) Updated: 2011-07-26 07:12As Flight AC29 arrived in Beijing on Saturday afternoon, Lai Changxing went from being the most-wanted fugitive to illustrating the country's resolution to punish crime.

|

|

Lai Changxing signs the arrest document upon his transfer from Canadian to Chinese police at Beijing International Airport on Saturday. Lai was accused in 1999 of smuggling 53 billion yuan in goods and bribing officials while he was chairman of the Yuanhua Group in Xiamen, Fujian province. He fled to Canada with his family. Zhang Jianxin / Xinhua |

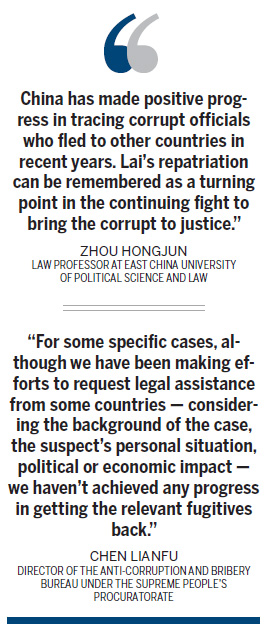

"China has made progress in tracing corrupt officials who fled to other countries in recent years," Zhou Hongjun, an international law professor at East China University of Political Science and Law, said.

"Lai's repatriation will be remembered as a turning point" in the continuing fight to bring the corrupt to trial, he said.

The transition at Beijing airport was routine: Canadian officers handed Lai over to Chinese police who announced his arrest.

The symbolism, however, was uncommon. Experts say the repatriation of Lai, whose legal odyssey in Canada began in 2000, is intended to deter criminals who think they can flee the country and remain free.

Lai was accused in 1999 of smuggling 53 billion yuan ($8.2 billion) worth of goods and of bribing officials while he was chairman of the Yuanhua Group in Xiamen, Fujian province.

The corruption scandal became one of the largest in modern Chinese history, with scores of high-level municipal and provincial officials sacked and imprisoned. In 2000, a Chinese court sentenced 14 people to death, 12 to life in prison and 58 to other prison terms for their involvement, Xinhua News Agency reported at the time.

China has worked to get Lai back since he was arrested in 2000 for immigration vio-lations in Canada, where he fled with his wife and three children via Hong Kong in August 1999. Canadian courts denied a 2006 request to deport Lai, with the judge saying he didn't believe China's pledge not to execute Lai. Canada does not have the death penalty.

The majority of corrupt officials who have skipped the country were engaged in construction engineering or finance sectors, said Chen Lianfu, director of the Anti-Corruption and Bribery Bureau under the Supreme People's Procuratorate.

"More than 90 percent of them were accused of corruption, bribery and embezzlement," he said, "and they transferred the illegal proceeds mainly through money laundering, illegal investment and underground financial institutions."

Those are among the eight money-transfer channels, used since the late 1980s, identified in a report last month by the China Anti-Money Laundering Monitoring and Analysis Center, which was set up by the People's Bank of China.

However, the exact amount of assets transferred remains a mystery.

The situation has persisted, although a government has intensified over the years.

From a criminal perspective, fleeing the country offers low risks and high rewards. Those on the other side of the law see it differently.

The ability of corrupt officials and business people to escape with impunity not only damages China's image internationally, but also undermines people's trust in the government, said Liu Qinglong, a sociology professor at Tsinghua University.

"Our country is still at the early stages" of tracking down such fugitives, he said. Some haven't been found yet; others are in countries without extradition treaties with China and "remain out of legal reach. The fight still has a long way to go."

Hurdles to jump

|

|

Yu Zhendong (middle) arrives in Beijing in 2004 on a repatriation flight from the United States. The former president of Bank of China's Kaiping branch, was accused of embezzling of 4 billion yuan. Yuan Man / for China Daily |

Chen said three major legal issues hamper China's efforts to bring fugitives back to China for trial - the absence of extradition treaties, differences in social and legal systems, and the slow pace of integrating international conventions into domestic laws.

China has signed extradition treaties with 37 countries, but not Canada and the United States. Many Chinese criminal suspects have fled to those countries as well as to Australia and some Southeast Asian nations because of their different political, ideological and legal systems, he said.

As in Lai's case, fear of the death penalty is one claim that some suspects use in fighting repatriation. Fear of torture is another.

Meng Qingfeng, director of the Public Security Ministry's economic investigation bureau, had this comment: "China will comply with the relevant international conventions to protect the human rights and other legitimate interests of them in line with Chinese laws and regulations.

"Our judicial authorities will treat them in a just and reasonable manner in strict accordance with Chinese laws."

Chen also said that China and other countries signed UN conventions against corruption and against transnational organized crime at different times, so integrating the international conventions into their domestic laws is proceeding at different speeds.

China also has entered into 106 legal assistance agreements with 68 countries and regions, according to Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Results have been mixed.

"For some specific cases, although we have been making efforts to request legal assistance from some countries - considering the background of the case, the suspect's personal situation, political or economic impact - we haven't achieved any progress in getting the relevant fugitives back," Chen said.

The problem was echoed by the Canadian side. George Prouse, team leader of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, told China Daily during an earlier interview, "Although I can't comment about some specific case... it can sometimes be a long and, at times, frustrating experience when you consider what is involved in the legal process. Especially for some special specific cases, delays are inevitable."

Sound mechanism

Experts say it is high time that the government reflect the reasons that official corruption continues, despite intensified anti-corruption efforts.

Hu Xingdou, an economics professor at Beijing Institute of Technology, said, "China's task of fighting corruption must be built on the establishment of a modern corruption-preventing system." Such a system, he said, would comprise disclosure by officials of their assets; the news media acting as watchdogs; and "the independent investigation of judicial departments."

Such a system, he said, would provide the transparency needed to discourage corruption by public officials.

Hu also said China needs to update its law on extradition. International circumstances and relations have changed dramatically since the law took effect in 2000, he said.

"Without the binding extradition contracts, the repatriation of a person from another country often lasts a long time in negotiation and involves high cost," said Sun Kui, a senior lawyer with Beijing Anheng Law Firm.

Chen, from the Anti-Corruption and Bribery Bureau, would like to see a more cooperative approach.

Countries of the world should rise above the differences in their political, economic and legal systems, he said. They should take a common principle and position, make joint efforts to create an environment against corruption, and allow no criminals to get away with impunity.

Yang Wanli and Zhang Yucheng contributed to this report.

- Seven villagers murdered in N China

- China steps up tobacco control efforts

- Five jailed for separatism in Xinjiang

- Letter asks for leniency in poisoning case

- Antibiotics in surface water pose 'indirect health risk'

- Tianjin airport opens up transit link to Beijing

- High levels of antibiotics in China's major rivers

- China to dig tunnel for Asian rail system

- Bering strait line to US possible, experts say

- China: Stop oil rig harassment