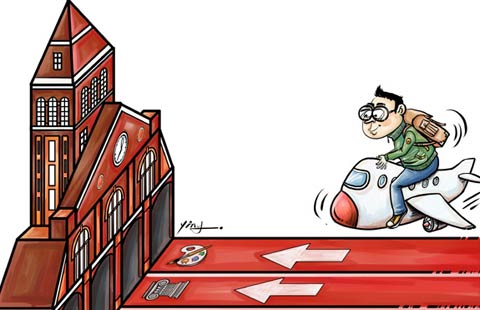

Rural students can feel a class apart

By Wang Hongyi (China Daily) Updated: 2011-08-29 07:57Liu Yuchen enjoys strolling in Fudan University's campus and spending time with classmates. "It's really good to study here, and students get on very well with each other," he said. "But I also want some guys who talk the same language."

|

|

New students start to register, making Peking University in Beijing a busy campus over the weekend. Many students from comparatively poor families find it's getting harder for them to qualify for China's top universities. [Photo/ China Daily] |

This is not a matter of Mandarin versus English or a local dialect. It's the language of familiar experience.

"Most of my classmates are from big and affluent cities It's hard to find someone who has a family and educational background like mine."

Among 100 or so chemistry majors, Liu is one of a handful from small or remote areas.

Nor is it a matter of occasional loneliness. Students from poor, or even just rural areas, are at a distinct disadvantage in their schooling when compared to urban students or those at provincial "super-schools".

"To some extent, where people are born largely determines their chances of educational success," sociologist Gu Jun said. "Education holds the key to improving social mobility, tackling poverty and extending opportunity for all."

And that key is out of reach for many Chinese students.

Liu was born 21 years ago in Wuqiao, in North China's Hebei province, a county known for little besides being the cradle of acrobatics. He knows he was lucky to get into one of the country's top universities, but he made some of that luck happen.

"After I finished my high school entrance exam, I knew that a key high school in the provincial capital organized an independent exam to enroll the best students provincewide. So I took and passed the exam," he said.

Then Liu walked out of the county where he had lived for 15 years, and spent three years at Shijiazhuang No 2 High School. The school is known for its education quality and high admission rate into top universities via the national college entrance exam.

"In 2008, when I graduated, about half of the 2,300 students in my school entered first-tier universities. This is a very high proportion compared with schools in my county," Liu said.

There, only about 80 of more than 500 graduates got into first-tier schools.

"If I hadn't had the chance to take the exam and study in the province's high school, I most likely would not have made it into Fudan University. My life would be the same as those who stayed in county or countryside schools."

Equity locally

How different are the schools? "At Shijiazhuang No 2 High School, I saw a lot of things that I couldn't see in my county - creative education concepts and methods as well as advanced education equipment. It was the first time I knew what true multimedia education is," Liu said.

|

|

"In the past, study was mainly based on textbooks," he said. "Now it depends more on the resources that can be used. Urban students can take courses online and can download education materials easily, while students from the countryside have less access to the Internet and know little about the outside world."

Almost every province has one or two superschools like the one Liu attended, usually in the capital or developed cities, that dominate local education resources. They receive regular funding and other support from local government, and they absorb the best teachers and students by a wide margin, shortchanging other schools.

In Hebei province, for example, Hengshui High School is known nationally for its militarized management and high admission rate at key universities. Last year, about 85 percent of its 2,400 graduates entered first-tier universities, and 84 of them were accepted by top-ranked Peking and Tsinghua universities and the University of Hong Kong.

In addition, more than 40 students were sent to the country's top universities by recommendation, an option generally reserved for superschools. It allows students with good grades and particular talent to be recommended to top universities without taking the national exam.

"Students like us have to be outstanding enough to be enrolled into such superschools and get the higher standard of education," Liu said. "If not, we have to stay at a county-level high school, which means little chance to enter top universities, even if we work harder."

As it turned out, Liu won first prize in a chemistry exam for high school students and was recommended to Fudan's chemistry department. He did not have to take the national college exam.

Equity at the top

Education scholar Yang Dongping, a professor at Beijing Institute of Technology, has looked into the equity of higher education in China and has found that students from the countryside are concentrated at ordinary universities or junior colleges.

In Hubei province from 2002 to 2005, for example, the proportion of such students at junior colleges rose from 39 to 62 percent, and at military and normal colleges went from 33 to 57 percent. In Hubei's top universities, Yang found there were 17 middle-class students whose parents were officials or civil servants for every one student from a rural or unemployed family.

Yang Liang, who teaches at Zhejiang University, has noticed the trend. He sees fewer rural students there, while more "come from substantial families, and their parents usually have decent jobs and respectable social status."

At Peking University, about 30 percent of students from 1978 to 1998 came from rural families. It was about 10 percent in 2005, according to research from the university's college of education.

At Tsinghua University, 17 percent of students last year were from rural families. Yet such students accounted for 62 percent of all who sat for the national college entrance exam in 2010.

The matter of paying for top-ranked education doesn't appear to be an issue. Scholarships, work-study and other financial aid programs are widely available, several universities said.

For decades, the exam was the only chance for Chinese high school graduates to receive higher education. For many students from the poor and remote countryside, it was the most direct and effective way, sometimes even the last resort, to shake off poverty.

New criteria

|

|

A student takes delivery of a laptop on Saturday. He is one of 39 new students from poor families who received a computer as part of a gift package from Peking University. [Photo/China Daily] |

Then, in 2003, a policy was introduced to expand university enrollment to encourage wider access to higher education.

Peking University and 21 other top universities were allowed to use their own criteria to independently select 5 percent of their students. The pilot program was hailed as a significant improvement from the national entrance examination system, which has been widely criticized as fostering exam-oriented education.

The independent exam focuses more on testing students' comprehensive ability, such as creativity, imagination and learning skills. Many education experts believed it to be conducive to better understanding where students' talents lie.

But rural students say such an exam has nothing to do with them.

"The focus of the independent exam is mainly on the range of knowledge and vision, which urban students are better at," said Geng Zhao-hua, 25, who came from a farm family in Jiaozuo, Henan province. He graduated from Fudan University and now teaches there.

"The test includes knowledge of arts, music and high-tech, which are far from the usual life of a child from an ordinary farmer family," Geng said. "Study is their main subject, and they have no time to develop outside interests like urban students.

"In my university, I found that many college mates had overseas travel experience, such as summer camp in middle school, which could help broaden their sights. This is impossible for students from farm families."

Likewise, students whose families are well-off can attend special classes or hire private tutors to improve their grades. Poor families cannot.

The independent exam program has since expanded to nearly 80 universities, which some think means that more opportunities are closed to rural students. He Yunfeng, director of the Research Institute of Knowledge and Value at Shanghai Normal University, is direct in his assessment: "The independent exam is partial to students from developed areas and rich families."

Social mobility

Experts said that the low participation in higher education by rural students - particularly in the top universities - is one of the main obstacles to social mobility. The solution, they say, is to improve the quality of education in rural areas, giving students from villages a level of primary and middle schooling equal to that of urban children.

In some programs, they say, a quota should be used to give preference to farmers' children.

"The gap in educational success between urban and rural areas of the country is widening, despite the government's continuous stress on educational equity," said Gu, the sociologist, who is a professor at Shanghai University.

"Educational equity is the assurance that all students, no matter where they are from, can receive impartial treatment and have access to all education resources and curriculum. But the reality is that students from farm families cannot access the same education resources as their urban peers."

Unless obstacles to quality education are removed, Gu said, "Children just retrace their parents' steps."

- Seven villagers murdered in N China

- China steps up tobacco control efforts

- Five jailed for separatism in Xinjiang

- Letter asks for leniency in poisoning case

- Antibiotics in surface water pose 'indirect health risk'

- Tianjin airport opens up transit link to Beijing

- High levels of antibiotics in China's major rivers

- China to dig tunnel for Asian rail system

- Bering strait line to US possible, experts say

- China: Stop oil rig harassment