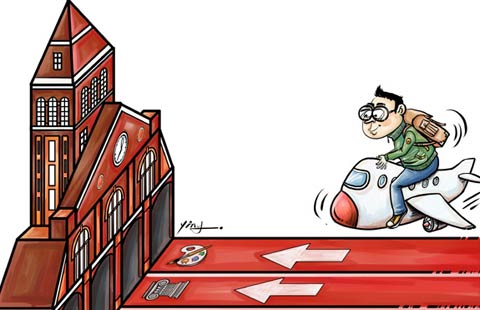

Fierce class battle leaves parents deeply frustrated

By Wu Yiyao (China Daily) Updated: 2011-10-13 08:14

One month after Shanghai kindergartens started the autumn term, Leslie Johnson's 3-year-old son has still not been offered a place in any classroom.

Johnson spent three months calling and visiting more than 20 kindergartens in the city, to no avail.

"I could not even get Richard on the waiting list at most kindergartens I contacted," Johnson, a US citizen, said. "The competition for a place at kindergarten is even fiercer than for college."

Full occupancy is not her only problem. So is the fee.

"I can't understand the costs," said Johnson, a market research project coordinator who is newly settled in Shanghai.

"My budget is $5,000 a year, including school bus and lunch, but I realized that it is far from being enough."

As a foreign national, her son cannot attend a publicly funded kindergarten. Private schools are the only choice, but most charge more than she can afford.

"I did consider the cheaper ones, but the catering and security are not satisfactory," she said.

Johnson also was upset when she learned that other parents had given red envelopes - traditional containers for cash gifts - to staff members at kindergartens, seeking enrollment favors.

"In the first place, I am reluctant to get involved in such bribes. I would find it difficult to explain to my boy why I would bribe a teacher or administrator at kindergarten.

"Even if I do some other tricks," she said, "I would be late, because many other parents have done the same, if not better ones, several months ahead of me."

Not enough room

In Shanghai, parents need to start trying to reserve a place at kindergarten one or two years before enrollment. There are too few schools for the number of children.

The Municipal Education Commission said that in 2010, Shanghai had about 400,000 kindergartners, nearly 70 percent of them with hukou, permanent residency permits. To keep pace, the commission said last year it had built more than 400 kindergartens over the previous five years.

Earlier this year, the city announced a new round of expansion, saying 100 more kindergartens would be built within three years. Meanwhile, private kindergartens are encouraged to supplement the public preschools.

Additional data come from a preschool education research team with the Shanghai Municipal People's Congress: At the end of 2010, Shanghai had 1,252 kindergartens, nearly 70 percent of them public. The number of kindergartners will reach 500,000 next year.

China's residence system is still the main barrier to public nurseries and schools for people without hukou. The city's education commission said last year it was considering easing the kindergarten admission policy, but neither conclusion nor timeline has been issued.

There are other factors beyond simple supply and demand that affect Chinese citizens and expatriates. Beijing, for example, has about 1,200 public kindergartens, but about 800 are designated for the children of government, military, university and civil organization employees.

Beijing has 18 international institutes that are approved for kindergarten education. Sixteen of them are allowed to enroll local pupils, cramping the space available for expatriates.

Zhang Lu, father of a 3-year-old girl in Beijing, said the most popular kindergartens in the city are European-style or international kindergartens for children of diplomats and expats. "But many Chinese parents are elbowing to get their kids in," he said.

- Seven villagers murdered in N China

- China steps up tobacco control efforts

- Five jailed for separatism in Xinjiang

- Letter asks for leniency in poisoning case

- Antibiotics in surface water pose 'indirect health risk'

- Tianjin airport opens up transit link to Beijing

- High levels of antibiotics in China's major rivers

- China to dig tunnel for Asian rail system

- Bering strait line to US possible, experts say

- China: Stop oil rig harassment