Schools build the mind, not body

By Tang Yue in Tianjin and Yang Wanli in Beijing (China Daily) Updated: 2011-12-05 07:28Chinese students forced to sacrifice sport, exercise for extra time in classrooms, report Tang Yue in Tianjin and Yang Wanli in Beijing.

The Chinese-language teacher "borrowed" the time allocated for physical education. Again. Instead of 45 minutes of running and playing, there was a quiz on reading and writing.

"We're used to it. We knew she would never pay (the time) back," Rong Yiyang, a third-grader, said as he blinked behind his glasses.

Losing a sports lesson that Tuesday morning pained him more than ever. The 9-year-old boy had just quit the school's basketball team because practice was conflicting with his after-school English class.

Here comes the unwritten rule for Rong and most other Chinese students: Exercise is not bad, but study takes priority - despite a nationwide requirement that schools get kids moving regularly.

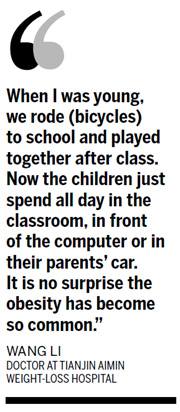

With "highly dedicated" teachers of major subjects, and "tiger mothers" and "wolf fathers", Chinese children become better at solving complex mathematics problems and speaking a foreign language, but they pay the price in excess weight and decreased physical ability.

Strength, endurance, explosive force and flexibility have all diminished since 1985, when the Ministry of Education began nationwide testing of students ages 7-22 every five years. Running 1,000 meters, for example, serves as an index of endurance. Today's 12-year-old boys take one minute longer to finish the run than those in 1985.

Many factors contribute to the phenomenon, including longer hours in front of the computer and more McDonald's and KFC, experts say. But the lack of exercise - due to the heavy burden of study and parents' failure to grasp the importance of exercise - is mainly to blame.

'His happiest moment'

Yiyang studies at one of the best primary schools in Tianjin. He gets up 6:50 in the morning on school days, and his father drives him to school. They have to arrive before 7:40, when the morning reading starts. A student who is tardy three times must write a paper of self-criticism.

He gets home at 4 in the afternoon and starts doing homework. After dinner, he gets back to his schoolwork for some English reading and listening until about 8:30. And then it's bedtime.

The kids at his school are scheduled for four lessons of physical education a week, but that's not always how it turns out. On weekends, Yiyang's schedule includes an eye checkup at the hospital every two weeks, homework, mathematics class and sleeping. Exercise hardly squeezes in.

Posted on the living room wall for the nanny is a highly detailed, hand-written guide to looking after the boy, including one that reads, "Use the blue quilt when the indoor temperature reaches 23 degrees Celsius." There is no room for exercise among the note's 23 points.

"I love sports very much," Yiyang said. "I can play basketball, tennis, pool and badminton. But I have to wait until summer vacation."

He actually plays basketball sometimes after school or with his father, but his mother worries that he'll catch cold, as he has in the past.

"I can tell he enjoys playing on the court very much. It is his happiest moment in life," said his mother, Yang Hua, 45.

"But in the winter he always coughs and has a running nose. Sick leave means more homework and more to catch up when he goes back to school. Then it leads to a heavier mental burden for the child and makes him more vulnerable to disease. I really don't know what to do."

An extravagance

Students always find their leisure time shrinks as they approach the entrance examination to the next level of study.

And those in provinces with big populations have much more demanding schedules. Unlike students in municipalities such as Tianjin, they have a slimmer chance of enrolling in the top universities under the existing college entrance examination system.

It has been five years since Bi Nan graduated from senior high school. But the 23-year-old from Henan, the country's third most populous province with nearly 100 million people, clearly remembers the hellish days.

All the students were seated in the classroom by 5:30 am and stayed there, except for mealtime, until 9:30 pm. Some would go to bed then, while others would study in the restroom or with a flashlight in bed.

Sports education lessons once a week in the first five semesters fell to zero in the sixth. Time was so precious that even eating and getting sick were "a waste of time", Bi said.

"We ran to the dining hall every day and ran back to the classroom as soon as we finished the meal. So it was not surprising that a lot of us had stomach problems at that time.

"I felt really tired and always caught cold," she said, "but there was really no time for sick leave. You just took medicine and conquered it."

Playing sports was considered extravagant back then, Bi said. Soon after she started college at Nankai University in Tianjin, she picked up the badminton racket again and fell in love with Latin dance.

"It makes me feel energetic again," she said with a big smile.

Everyone exercises

According to research conducted by the National Institute of Education Sciences, 20 percent of Japanese students exercise for at least two hours every day. In China, the figure is 6.3 percent. South Korean students also work out more regularly.

"We also have high pressure from the exams but physical education won't be replaced by other subjects," said Choi Kwang-won from South Korea, a junior English major at Nankai University. "Teachers and parents supported me to get some exercise after school, even when the test was coming."

Ji Ming feels the difference. The 18-year-old studied at local primary and junior high schools in Cangzhou, Hebei province, and then his parents sent him to Australia three years ago for high school. (Ji is not his real name. He said he didn't want to be identified.)

"In theory, I should be busier in senior high school, but it turned out to be much more relaxing." Ji said he played basketball for about two hours every day in Sydney.

"Almost every student there can master a few sports, be it ball games, swimming or even cross-country. It is impossible in my hometown."

- Seven villagers murdered in N China

- China steps up tobacco control efforts

- Five jailed for separatism in Xinjiang

- Letter asks for leniency in poisoning case

- Antibiotics in surface water pose 'indirect health risk'

- Tianjin airport opens up transit link to Beijing

- High levels of antibiotics in China's major rivers

- China to dig tunnel for Asian rail system

- Bering strait line to US possible, experts say

- China: Stop oil rig harassment