The grapes of wrath

By Shao Wei and Qiu Bo (China Daily) Updated: 2011-12-12 07:44

|

|

|

Tang Jianbo, 26, a farmer in Alaer in Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, checks dried jujubes in his field before loading them onto a truck for delivery to Shanxi province. Shao Wei / China Daily |

Farmers at the mercy of market turmoil and the weather as prices for crops continue to fall, Shao Wei reports from Xinjiang and Qiu Bo from Beijing.

There's a saying in the West that you can make a small fortune in farming, provided you start with a large one. Chinese farmers would understand.

Price turmoil hit cotton, cabbage and potato crops this year and is leading jujube farmers to sell crops well below cost or store them over the winter, adding to their expenses.

|

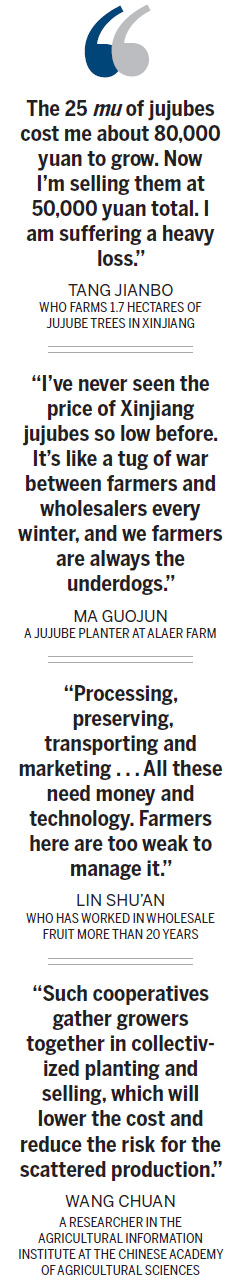

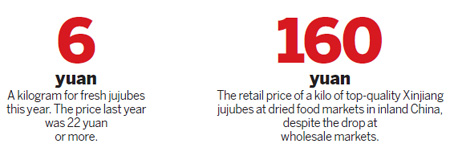

"We have to get rid of our jujubes before they start rotting," farmer Tang Jianbo said. "They are 6 yuan (95 US cents) per kilogram now, while last year they were 22 yuan at least!"

The price of ginger has also fluctuated wildly over the last five years and speculators last year fueled huge swings in garlic, apple and mung bean prices.

The government guarantees minimum prices each year for the critical wheat, rice and corn crops. But most farmers are at the mercy of the market. And the weather, which often affects prices. Greater knowledge of the market and better channels of information would help, some experts say. So might changes in the ways crops are sold.

Farmers seldom expect to get rich, but they'd like at least a little profit and consistency.

Jujubes are sweet fruit, similar to dates, that are sold fresh or dried. Chinese consider them antianemic and good for the skin, and the fruit is popular in inland China.

Tang, 26, farms 25 mu (1.7 hectares) of jujube trees at Alaer Farm in Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. On a recent Sunday, he was loading dried fruit from his field onto a truck heading to Shanxi province.

The orchard is in southern Xinjiang's Aksu prefecture, which is famous for its high-quality jujubes and melons. The farm, operated by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps in Alaer city, has about 21,300 hectares of jujube orchards. Output this year was 23,800 tons.

"The 25 mu of jujubes cost me about 80,000 yuan ($12,600) to grow. Now I'm selling them at 50,000 yuan total," Tang calculated. "I am suffering a heavy loss."

Even so, Tang considered himself lucky. Most of his neighbors, who couldn't bear the steady drop in wholesale price when jujubes ripened, dumped their fruit in late November for 4 to 5 yuan per kg.

Tang figured about 95 percent of jujube growers at the farm made no money this season.

It's not just fruit

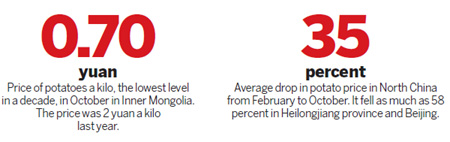

Potato prices hit their lowest level in a decade in October, at 0.70 yuan (10 US cents) a kg in North China's Inner Mongolia autonomous region. The price in Ulanqab, which calls itself the "potato capital" of China, last year was 2 yuan a kg.

Farmer Sun Guanbing said in October that he sold only a quarter of his yield. "I earned some 30,000 to 40,000 yuan last year," Sun said, "but I will probably suffer at least a 20,000 yuan loss this year.

Prices elsewhere in North China dropped an average of 35 percent from February to October, as much as 58 percent in Heilongjiang province and Beijing.

|

The garlic roller coaster ride began at the end of 2009 and peaked last year "when some opportunist speculators sought to jack up the price of garlic," said Wang Chuan, a researcher in the Agricultural Information Institute at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Speculators took advantage of the relationship between supply and demand, said one in Shandong who gave only his surname, Qin. When the price, which had been steady at 1 yuan a kilogram, slumped to 0.1 yuan, he said, speculators perked up.

Qin, a wholesaler, signed deals with garlic growers promising to buy their crop at the relatively high price of 3,000 to 4,000 yuan for every mu when it ripened. Then he sold his contracts, covering 97 mu, for more than 7,000 yuan a mu. And those buyers stored the garlic, selling it for much more. The retail price increased a hundredfold within two years, growing more expensive than meat.

|

|

- Seven villagers murdered in N China

- China steps up tobacco control efforts

- Five jailed for separatism in Xinjiang

- Letter asks for leniency in poisoning case

- Antibiotics in surface water pose 'indirect health risk'

- Tianjin airport opens up transit link to Beijing

- High levels of antibiotics in China's major rivers

- China to dig tunnel for Asian rail system

- Bering strait line to US possible, experts say

- China: Stop oil rig harassment