Empty homes, broken families

By He Dan (China Daily) Updated: 2012-04-24 07:53Parents who have lost their only child are increasingly worried about how they will cope when they grow old. Our reporter, He Dan, traveled to Wuhan and Nanchang to hear their stories.

Mei Yunqing, 52, lay quietly on a couch at his home in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, wearing a striped sweater that once belonged to his dead son.

"I asked him to wear it. I hope our son in heaven will bless his sick father," said Mei's wife, 49-year-old Zhang Taomei.

In 2007, their son, a 16-year-old high school basketball star, died from head injuries he suffered in a bad fall on the court. A year later, Mei suffered a stroke that left him blind and unable to walk. "My husband didn't like to speak about the pain (caused by the loss of their son). Instead, he turned to alcohol and that has ruined his health," said Zhang, who had recently undergone surgery to treat thyroid cancer. She also suffers from acute insomnia, which she believes is the result of overwhelming grief and depression caused by her son's death.

Their monthly income of 1,900 yuan ($300) barely covers medical bills and living expenses. "I dare not think about our old age," admitted Zhang. "We have no savings, so we can't afford to hire a maid or live in a nursing home."

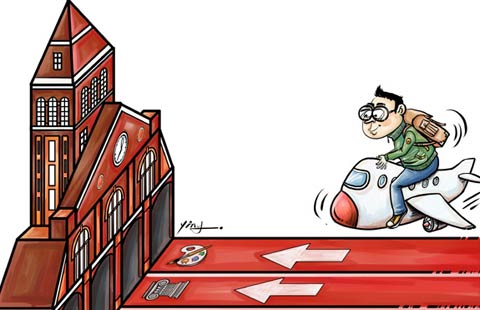

Many aging couples in China face this problem. Traditionally, children become the main providers for their elderly parents. However, if the only child predeceases the parents, they are often left in financial and social limbo. A population and family planning law enacted in 2001 said that local governments should provide "necessary help" to couples who have lost their only child, but are incapable of conceiving again or adopting a child.

In 2007, the National Population and Family Planning Commission started a project to provide help for such couples and urged the provision of a monthly subsidy of not less than 100 yuan to each parent. In Shanghai, the sum has been raised to 150 yuan, but it's still a drop in the ocean. "It's better than no subsidy at all, but it isn't enough to improve our quality of life," said Zheng Puli, a 61-year-old Shanghai resident, whose daughter died in 2007.

China launched its family planning policy in the late 1970s. It's estimated that there are 120 million households with one child on the mainland, accounting for about 30 percent of the national total, according to Zhai Zhenwu, a leading demographer from the School of Sociology and Population Studies at Beijing's Renmin University. He predicted that by 2020, at least 1 million couples who have complied with the policy will end up childless, because some of those children will inevitably die as a result of illness, traffic accidents or other factors.

- Seven villagers murdered in N China

- China steps up tobacco control efforts

- Five jailed for separatism in Xinjiang

- Letter asks for leniency in poisoning case

- Antibiotics in surface water pose 'indirect health risk'

- Tianjin airport opens up transit link to Beijing

- High levels of antibiotics in China's major rivers

- China to dig tunnel for Asian rail system

- Bering strait line to US possible, experts say

- China: Stop oil rig harassment