Making inroads to a place where time stands still

By Hu Yongqi and Li Yingqing (China Daily) Updated: 2012-11-28 02:12

As dusk fell in Xiongdang village, deep in the shade of the Gaoligong Mountains in northwest Yunnan province, Li Songying's relatives and friends gathered around a fire pit fenced with bricks to protect the small, wooden house. The slices of pickled pork suspended above the flames swayed in the warm air and a chicken boiled slowly in a pot of rice wine, diffusing an appetizing smell.

Welcome to a party of the Derung ethnic group. After serving cooked taro and corn, Li Songying, 48, joined the fun and games. Losers in one game, where players attempt to correctly guess the number of fingers their opponent will hold up, have to perform a "forfeit" by quaffing a cup of the lethal "chicken soup".

The party ended at midnight, when the wine jars were finally empty, and the guests lay down to sleep on a piece of plastic sheeting next to the fire.

Next morning, as the first sunlight hit the village, the three hills hugging the contours of the Dulong River — rolling along like a blue ribbon unfolding in a stream of blue and white bubbles — resembled a beautiful landscape painting.

Li Wenshi, 73, one of the few remaining Derung women with facial tattoos, shares an amusing moment with her daughter Li Yuhua at their home in Yunnan province. Wang Jing / China Daily |

Xiongdang, deep in the hills that straddle the border with Myanmar, is the most isolated settlement in Dulongjiang township, located at the far end of the road that links the two. Even in good weather when the road is free from landslides in the rainy season, it takes three days to travel by bus from the provincial capital Kunming to the Gongshan Derung and Nu autonomous county and a further seven hours by car to the township.

Residents of Xianghong village, which has no road, face a seven-day trek if they need to visit the township government.

From November to June, the road is regularly rendered impassable by snow, which can lay 10 meters deep. Infrequent interaction with the outside world has sheltered the area from modernity, but it has also condemned the residents to a life of economic disadvantage.

The ethnic group was historically known as the Qiu people, but was renamed by former Premier Zhou Enlai in 1954 to Derung, meaning "single dragon" in Chinese.

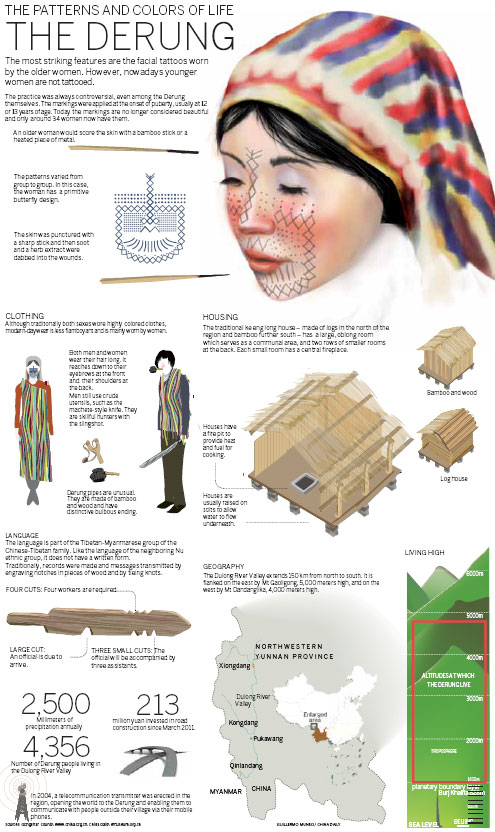

Roughly 60 percent of the Derung live along Dulong River. Once they were famous throughout China for the facial tattoos sported by the womenfolk, but the practice is fast disappearing.

Li Wenshi, 73, and Lian Zixian, 74, both have facial tattoos, but the seven other girls tattooed alongside them as teenagers have passed away.

"The girls were bound with rope and the mother would hold her daughter's face still," explained Li Wenshi. "The tattooist scratched the design into their flesh with a sharp, red-hot chisel and then filled in the scars with ink made of soot from the bottom of cooking pots. The bloody scars took a week to heal and the girls' faces were swollen for at least five days."

The practice was forbidden during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and has never restarted, leaving those still bearing the tattoos as living historical relics.

The Derung people were too weak militarily to resist invasion from, among others, slave drivers from Tibet. According to the most widely accepted account, this resulted in the elders deciding to make the girls "ugly", and thus undesirable to invaders, by tattooing their faces. The tradition stuck and the indelible markings came to represent courage and became a prerequisite for marriage.

Only 34 tattooed women are left in the township, according to records at the Dulongjiang Frontier Police Station, and the youngest is 56. Two or three die every year, meaning that within a decade all trace of the practice could be gone. A series of photographs, taken when the local police station compiled health dossiers on the women, will be the only reminder of the tattoos that were once commonplace in the area.

|