Soul mates, sisters, and soldiers

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2014-06-23 14:13

|

|

Chen Baochen, 89, pictured alongside a statue of herself. The statue was erected last year at the site of a 1943 battle in Tengchong, Yunnan province, in which Chen participated. Provided to China Daily |

Testing as life at the academy could be, it was during the post-Whampoa days that the reality of war, filled with group sacrifices and personal loss, was fully brought to bear on the young women. Chen Baochen entered Whampoa in 1941, directly after graduation from a teacher training college in Yunnan province in the southwest of China. The only thing she ever wrote from the frontline was her will, addressed to her mother and penned on the eve of a fierce battle against the Japanese in July 1943. During the charge on the enemy-occupied highlands the day after she had written her will, Chen was shot in her right arm. Despite bleeding profusely, she lived to tell the tale.

"She had seen too many deaths to lament her own," said Su Shaolong, a 26-year-old university student who has joined an increasing number of volunteers across China who seek out the country's remaining World War II veterans to listen to, and record, their stories and ensure that their final days are lived in love and respect. "Even at age 89, she can still recall with great accuracy the scene that confronted her when she first entered a secret Japanese bunker after the Chinese victory. There, on the blood-soaked ground, were more than 60 'pairs' of dead Chinese and Japanese soldiers, all grappling together in the final act of killing."

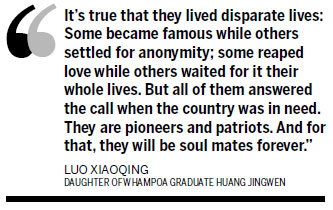

Some female alumni became martyrs, including, most famously, Zhao Yiman, Huang's classmate, who was captured, tortured and executed by the Japanese at the age of 31 in 1936, before the official start of China's eight-year struggle against the invaders. Zhao's last letter to her only son, written in prison shortly before her execution, struck a deep chord with a generation of Chinese who followed in her footsteps.

According to Wang Yi, a high-school teacher turned amateur historian, many of the female Whampoa graduates worked at field hospitals, where they nursed the injured while contending with the daily reality of death. "All field hospitals were severely understaffed, and the soldiers who'd had their limbs blasted away often died in agony. As a result, the doctors and nurses were quite literally enveloped by a sea of endless groaning and imminent death," Wang said.

The 55-year-old has maintained close contact with two of the Whampoa graduates, Zhou Yuyun and Zheng Miao, who both served as field nurses during WWII. "They told me their job was to heal the soul as well as the body, and to console the inconsolable, those who had been crippled in the war and had no idea where their futures lay," she said. "Sometimes, illiterate soldiers asked the nurses to write letters home, and they readily obliged. Both recounted their experiences of throwing themselves across the bodies of the wounded during an enemy air raid."

If anything, the tragedy and chaos that engulfed China between the 1920s and 1940s only makes Hu Lanqi's story all the more exceptional. An early Whampoa graduate, Hu was a staunch revolutionary and a bold beauty who, to use her own words, "was always riding the crest of a wave, despite being repeatedly thrown onto the hard rocks". A Communist, who was promoted to the rank of major general by the Nationalist Government in the early 1940s, Hu was a lover - and many believe the lifelong love - of Chen Yi, one of the 10 marshals of the People's Republic. In December 1932, Hu made a speech at an anti-Nazi rally in Berlin, which led to a three-month prison sentence and in turn gave rise to her best-selling book In a German Women's Prison. A close friend of Maxim Gorky, Hu helped to carry the Russian writer's coffin at his funeral in 1936.

"It's true that some of these women belonged to the social elite and were indeed legendary," said Chen Yu, the Whampoa historian and a prolific writer. "But the true legend of the Whampoa women goes far deeper than that, in their unyielding spirit which lived on, probably more vigorously, in the latter half of their lives," he said, adding that the overwhelming majority of the women who enrolled at Whampoa in the 1930s and 40s had fought under the Nationalist flag. However, when World War II ended, the civil war began, and ending in victory for the Communists and the founding of the People's Republic of China in October 1949. "For the next three decades, those who had been affiliated with the Nationalist Party were put through a really hard time," Chen Yu said.

- Courts in China to look out for lawyers

- China to accelerate development of insurance sector

- Electric-car buyers to get

tax exemption - China's progress on health reform 'remarkable'

- China's next kungfu masters

- Mermaids splash coolness to Nanjing summer

- Li: Govt will boost input for healthcare

- Colleges to retest athletes who got gaokao bonuses

- Top court to raise judges' pay

- JV to pay maximum fine for polluting air