Learning the lessons of history

By He Na (China Daily) Updated: 2014-07-04 08:44Documents unveiled by the Provincial Archives in Jilin province have cast fresh light on atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army during the occupation of China, as He Na reports from Changchun.

In the same week Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced that his cabinet had endorsed the "reinterpretation" of a constitutional clause that outlaws Japan's use of armed force in all but the most serious situations, further evidence has emerged of atrocities committed by Japanese troops during the occupation of China before and during World War II.

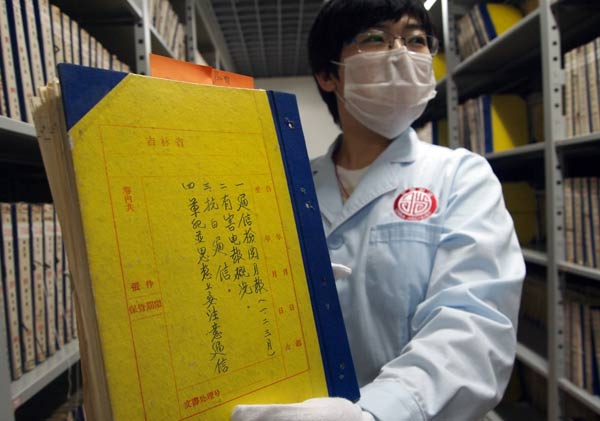

On Tuesday, the Jilin Provincial Archives released a batch of 450 recently translated files culled from confidential Japanese wartime archives in Changchun, the capital of the northeastern province. According to experts, the archives contain rare, firsthand information that sheds fresh light on the activities of Japanese soldiers during the occupation.

The files, which constitute a fragment of the 45,000 documents detailing monthly reviews and censorship of reports, letters, telegrams and other communications, were discovered at the former headquarters of the Kwantung Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, in Changchun.

The communications, written in Japanese by officers and regular soldiers, span the period 1937 to 1945. They were subject to monthly reviews in which the Kempeitai attempted to prevent evidence of atrocities and brutality from reaching the eyes and ears of the general public in Japan and elsewhere.

Mu Zhanyi, vice-director of the Jilin Provincial Archives, said that during the occupation of China and other countries, the Japanese authorities sought to prevent leaks of confidential military information, and descriptions of arson, looting and murder committed by the Japanese military. The Japanese government set up a strict inspection system for military and civilian communication within the countries it occupied. The scope of inspection included Japanese immigrants to China, people living in the countries colonized by Japan, and foreigners, especially missionaries.

"Kempeitai in various locations compiled the 'Monthly Postal Review' which reported to the Kwantung Kempeitai Headquarters, and was circulated between the Kempeitai and troops that had been sent to the front. The 'prohibited content' in the letters and telegrams truthfully reflect the crimes committed by the Japanese military," Mu said.

According to Mu, the documents, designated "confidential", contain vivid, detailed descriptions of almost every aspect of Japan's invasion of China and other countries, including atrocities committed against civilians and troops, colonization strategies, bacteriological experiments conducted by the mysterious Unit 731, and even a growing sense of war weariness among the Japanese military.

Discovery

The archives were discovered during the 1950s during construction work in a yard behind the offices of the Jilin provincial government, which were used as the headquarters of the Kwantung Kempeitai during the Japanese occupation. Historians and researchers have been painstakingly poring over the documents since the 1980s.

The records were discarded during the Japanese army's hasty retreat from Changchun, which was called Hsingking at the time and was the capital of the puppet Manchurian State established by the Japanese, after the country's surrender on Aug 15, 1945. Although many of the archives were burned, the rapid advance of the Soviet army left the occupiers little option but to bury huge numbers of documents.

"Nothing can be more convincing than these postal review archives. The Japanese recorded what they experienced and saw, so the files contain firsthand information. The letters have the names of the senders and addressees, where they were from and which units they belonged to," said Jiang Lifeng, a research fellow at the Institute of Japanese Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who has called for contact with the offspring of those who wrote the communications so the authenticity of the archives can be proved beyond doubt.

Atrocities

Yi Baozhong, a professor at Jilin University's Northeast Asian Studies College, was part of the team that collated and researched the material. He said the archives are of great historical value because the frank depictions of atrocities they contain undermine the case of right-wingers in Japan who deny that war crimes were committed.

"Since January, I've read so many of these documents that it feels as though my office has been moved to the Jilin Provincial Archives. The more I read and researched these files, the more I understood just how important they are. I'm sure even more evidence will emerge soon," Yi said.

The file for January 1938 notes that a Japanese soldier wrote two letters to a friend in Muroran-shi, Japan, in which he recorded the way the troops killed civilians. In the first letter, the soldier described how civilians were ordered to stand next to a pool, and then shot. The corpses were then thrown into the pool, "turning the water blood red".

In the second letter, the soldier told how he took a bound civilian to a riverbank: "I stabbed the bayonet into the man's belly twice, and suddenly blood dripped from his stomach. He fell down and I stabbed him once more in his chest, then I kicked him into the river. I felt very happy when I watched the corpse float away. I have killed two more people in the same way."

Similarly, the archive for July 1940 contains a letter written by a Japanese officer in Mudanjiang, Heilongjiang province, to a friend in Japan. According to the author of the letter, drunken Japanese soldiers poured onto the streets at weekends, harassing and assaulting unaccompanied women, and threatening civilians with bayonets.

|

| Special: China-Japan Relations |

Yi said: "The Monthly Postal Review was conducted and controlled by the Japanese Military Police. This archive material was all written by Japanese soldiers involved in the invasion of China, but the Japanese authorities thought the content of the letters was too cruel to be known by outsiders, so they impounded many letters."

The archives also record that Japan regarded Northeastern China as its lifeline, and hoped to use it as a base to conquer the far east of what was then the Soviet Union. To prevent a Soviet attack, the Japanese illegally forced hundreds of thousands of civilian laborers to construct defenses along China's borders with the Soviet Union and Mongolia. Most of the laborers were either killed when the work was completed, or died because of exhaustion and the harsh conditions, according to Jiang.

In the archives for September 1939, a Japanese officer in Hulin, Heilongjiang, wrote to a friend in Niigata in Japan and revealed that more than 50,000 civilians had been arrested and forced to build a railway. He added that a further 2,000 people would be "available" in October.

In May 1940, letters between two Japanese officers recorded the spread of typhoid in the region, and stated that treatment was denied to civilians with the disease. The authors noted that on May 20 alone, 24 Chinese laborers had died.

- New scare hits fast food chains

- New scare hits fast food chains

- Syndrome killing young workers in 'world's factory'

- Anti-smog gains marred by rising ozone levels

- Lawyers trained to help deal with transnational cases

- Man saved from suicide kills himself

- 17 dead, 5million affected by Rammasun

- Namtso no longer Tibet's largest lake: research

- Red Cross defends use of winter quilts in summer

- Meat supplier of McDonald's, KFC suspended