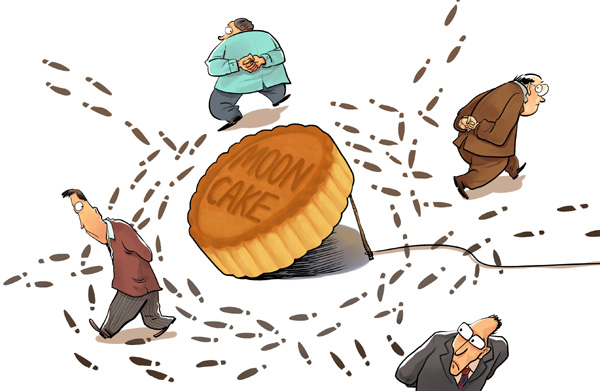

Mooncake sales wane

By An Baijie (China Daily) Updated: 2014-09-08 07:41

Mid-Autumn Festival gift-giving feels welcome effect of graft crackdown, reports An Baijie.

For civil servant Jin Bo, Mid-Autumn Festival used to be an exhausting affair. The official at a county in Dali, Yunnan province would be swamped sending and accepting gifts during the annual holiday. "I had to accept so many mooncakes as gifts that my family would have to eat them for breakfast for weeks," said Jin, who is not using his real name to protect his identity and keep his job.

|

Targeting 'elegant' bribes in crackdown The objects do not have fixed prices and the deals are often sealed privately. A painting at a gallery will not sport a price tag, bargaining is common at antique stores and at auctions, and bidders have only "high" or "low" estimates for reference. With these characteristics, works of art have long been viewed as a "grey area" opportunity for corruption - making it extremely difficult to identify precisely how much an art bribe is worth. Judicial prosecutors have recently been asked to brush up their knowledge of artworks and antiquities, so that they are better able to spot evidences of such yahui, or elegant bribery, in the behavior and activities of suspected corrupt officials. The far-reaching anti-corruption drive already seems to have hit yahui. Some auction houses have reported a drop in consignments from clients made up of government officials, retired and current. These boast rich collections of Chinese paintings and antiquities but dare not sell them at public auction for fear of being investigated, Chinese media reported. Beijing-based Art Market Monitor of Artron, an affiliation of Shenzhen printing company Artron, recently issued a report on the Chinese art auction market in the first half of the year. It predicted that unlike what had occurred in the past decade, the Chinese art market will experience minimal eruptions and rocketing prices in the coming five years, a response to the economic slowdown. The cooling down will be felt strongly in Chinese painting and not just because of economic factors, according to the report. The Chinese painting market has been increasingly criticized as a conduit for deals between money and power, and the central government has vowed to target yahui in its corruption crackdown. Art bribery dates back to hundreds of years and extremely corrupt officials such as Yan Song of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and He Shen of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) were among its most notorious examples. After the art market revived in the 1990s, works of art sold for up to several hundred yuan and appeared more as gifts centering on their aesthetic value. But as the market boomed and prices hit tens of millions of yuan, speculators looking for short-term gain flooded in the market. Works of art became a shortcut for cashing in, making it very convenient for yahui dealings. Some art market observers have questioned the extent that the anti-corruption drive can curb art bribery and whether a better way can be found to determine the true value of the bribes. Yahui-related pricing has disrupted the art market for years. There have been several cases of paintings in which investigators alleged involved bribes worth millions, only to find out the objects were deliberately overpriced. In other cases, officials sold a painting valued at several thousand yuan at auction only to have the bribers winning the bid by paying millions of yuan. These abnormalities cannot be eradicated if the market continues to function without a comprehensive pricing mechanism, analysts said. Some dealers and auctioneers have been fully involved in the "industry chain" of yahui. They help launder bribes and others consign a forged painting to dealers or auctioneers who then sell it to the bribers at the price of a genuine one. The practice of yahui reflects how bad the art market can be, when an independent authentication body has long been absent and cheating prevails without strict supervision, analysts said. |

The traditional mooncake gifts to mark the festival had gradually evolved into elaborately wrapped and expensive opportunities for people to present them to recipients whom they wished to build or maintain good relationships with.

That included businessmen trying to curry favor with officials like Jin.

Jin said that apart from accepting gifts, he also had to rack his brains to pick presents for his superiors during the festival - an "unwritten rule" among many government departments.

Some officials would also accept gifts from subordinates who used the gift-giving practice during the festival to try to get promoted, Jin said.

"In the past, there would always be some other luxurious products including imported wine, expensive seafood and even gold bars, packed into the boxes of mooncakes," he said, adding that he also got "surprises" in the gift packs for him.

He refused to disclose what kinds of gifts he had received in the mooncake boxes.

But with the central government's ongoing crackdown on graft, Mid-Autumn Festival is no longer a burdensome affair for those like Jin.

For Jin, the situation started changing last year after the Communist Party of China laid out clean-governance rules that banned government officials from buying or sending gifts at public expense during festivals like Mid-Autumn.

To push forward the rules, the CPC Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, China's top anti-graft watchdog, last month also started asking the public to submit online whistleblowing posts to expose officials' misdeeds during the festival.

"The change has put me more at ease, because it has helped stopped unnecessary social activities," Jin said, who also welcomes the return of the mooncakes to their original role as a food to mark the festivities and celebrate Chinese values.

Amid the strict ban on luxurious gifts, most domestic supermarkets have also withdrawn expensive boxes of mooncakes from the shelves. A report by Nanfang Daily said on Aug 29 that moon cakes cheaper than 100 yuan ($16.30) a box are most popular.

The public has lauded the disciplinary authorities' ban on buying gifts with public money during the festival. A number of public figures have similarly praised the efforts.

Chinese writer Feng Jicai said on Aug 28 that the mooncake is a traditional festival food and should not become a tool for corrupt officials to accept bribes.

"By adding luxurious products to the mooncake packs, we have lost a virtue of our tradition. Such misbehavior has also had negative effects on society," Feng said during an online interview by the top anti-graft watchdog.

Officials punished

At least three government officials have been punished for buying mooncakes at public expense or selling homemade mooncakes to their subordinates, according to a statement released by the top anti-graft watchdog on Aug 10.

In one case, Wang Gang, former director of the commercial bureau of Baishan, Jilin province, received a serious warning for buying mooncakes at public expense and giving them to bureau staff members, said the statement.

The statement disclosed 154 cases in which government officials were punished for violating the "eight-point rules" amid the frugality campaign.

The rules, put forward by the CPC Central Committee in December 2012, require government officials to rid their work styles of undesirable qualities such as excessive bureaucracy, extravagance and hedonism.

Last year, disciplinary authorities punished 30,420 officials for violating the frugality rules, according to the the CPC Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

The campaign has also affected sales of luxurious commodities like Moutai liquor. China's two biggest liquor makers, Kweichow Moutai and Wuliangye, reported declines in profits in the first half of this year.

Wuliangye's net profits in the first half of the year totaled 4 billion yuan, down 31 percent year-on-year, according to the company's interim report released on Aug 28. Moutai saw 7.23 billion yuan in net profits in the first half, down 0.25 percent year-on-year, said the company's interim report released on Aug 29.

The star product of the "National Brand" Moutai -the 500 ml bottle - was first sold at about 300 yuan ($48.84) before climbing to more than 2,000 yuan in late 2012. That year, the average per capita disposable income for China's urban residents was 2,047 yuan a month.

Those at the top end of the hotel industry, which reported business declines in 2013, have also asked to be downgraded to appeal to the mass market after the government banned officials from using luxury hotels.

Fifty-six five-star hotels sought to downgrade their ratings to four stars in 2013, while many more lower-rated hotels suspended their applications for the top rating, according to the China Tourism Association.

Wang Qishan, head of the top anti-graft watchdog agency, said at a meeting on Aug 25 that if basic issues like buying mooncakes and postcards at public expense are not well handled, misunderstandings between the government and the people will worsen.

Anti-graft authorities will keep a closer eye on government officials' misbehavior and have no tolerance for various corrupt activities, Wang told political advisors at the meeting.

Still, under the tough clean-governance rules, many businesses have taken less visible means to sell expensive mooncakes.

China Daily found that some online shops are selling "gift cards", which buyers can use to get products including expensive mooncakes through express services.

By using the gift cards, government officials can accept expensive gifts "safely" without being noticed, said an owner of one of these online shops who did not want to be identified.

But some netizens had submitted posts to the website of the top anti-graft watchdog in late August, exposing such "hidden avenues" for selling expensive mooncakes.

Zhou Shuzhen, a professor of clean-governance with Renmin University of China, said that by implementing the frugality rules, the government is expected to regain the public's trust.

"What the top anti-graft watchdog banned is not just a small mooncake, but a type of corrupt behavior that is hated by the people," she said.

Contact the writer at anbaijie@chinadaily.com.cn

- Govt encourages people to work 4.5 days a week

- Action to be taken as HIV cases among students rise

- Debate grows over reproductive rights

- Country's first bishop ordained in 3 years

- China builds Tibetan Buddhism academy in Chengdu

- Authorities require reporting of HIV infections at schools

- Typhoon Soudelor kills 14 in East China

- Police crack down on overseas gambling site

- Debate over death penalty for child traffickers goes on

- Beijing to tighten mail security for war anniversary