A war of words

By Peng Yining (China Daily) Updated: 2015-08-31 07:49

|

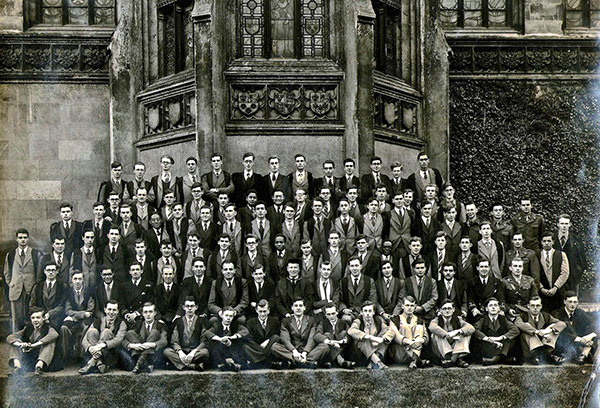

Ye(seventh from left, second row from back) with classmates at King's College, Cambridge, in 1945. Photo Provided to China Daily |

Bridging cultures

"Ye was a geographical bridge between China and the West in both directions," said Professor Alan Macfarlane, curator of the exhibition and a fellow of anthropological sciences, at the opening ceremony, which was attended by Liu Xiaoming, China's ambassador to the United Kingdom, members of Ye's family and Leszek Borysiewicz, the vice-chancellor of the university.

In an introduction to the exhibition, Macfarlane wrote that Ye brought news of China to the West, and on his return, his fluency in 12 languages, including French, Spanish, Danish and English, enabled him to take the West to China through his translations of European literary classics.

"My father never had a gun in his hands, and never stepped onto a real battlefield, but he experienced the bombings carried out by both the German and Japanese fascists and fought his battle with a pen and his words," said Ye Nianlun, Ye Junjian's son.

Ye was one of the few Chinese scholars at the time who was fluent in English, and his linguistic skills led to him being selected to tour Britain by the UK Ministry of Information.

Although he had a comfortable job teaching European literature at a university in Chongqing, the wartime capital, he packed his bags and traveled for two months, by mail boat and military plane, through Southeast Asia, India and North Africa before finally arriving in Britain.

After a week of rest, Ye began touring the UK to make speeches. His first audience was a group of volunteer firefighters and the theme of the lecture was "The life of the Chinese people at war."

Shortly after he arrived in the UK, Ye's hotel was hit by a "Doodlebug", a German V1 missile. "A loud sound woke me in the night. A corner of my hotel had collapsed," Ye wrote in his memoir. "I went back to sleep. I had no time to be scared. There was a lot of work to do the next day."

He traveled across Britain and Northern Ireland, delivering two speeches a day on average and often at different locations. He lectured at middle schools, farms, military camps, workers' associations, businesses, juvenile correction facilities, chapels and US military camps, and his audiences came from all walks of life.

Ye wrote that the British authorities didn't censor the content of his lectures, so he chose five themes: the life of the Chinese people at war; how the Chinese army overpowered the Japanese; the war efforts of intellectuals; why China would definitely win the war; and the Chinese people's hopes for the future.

"My aim was to work with the staff at the information department to encourage the British people in the fight against the fascists. To boost the confidence of the British people," he wrote in his memoir. "An impoverished country like China was still able to pin down the modernized Japanese army, so with the joint efforts of Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union, we could defeat the fascists."

Although the British people knew the basic facts about China's fight against the Japanese, Ye's lectures put flesh on the bones as he described people's living conditions, the agonies and humiliations they suffered and their hopes for the future.

- Delegation salutes Tibet anniversary

- Officials are told to act as anti-graft watchdogs

- Great Wall safeguarded in united action

- Vice minister pledges more efforts to improve air quality

- Beijing’s efforts to control air pollution start to pay off

- China's military committed to reform

- Netizens rip singer over baby photos

- Central govt's growing support for Tibet

- Monument to be built on Tianjin blast site

- China and Russia seal raft of energy deals