Waste collectors headed for the scrapheap

By Wang Yanfei (China Daily) Updated: 2016-01-13 08:22In December, the municipal environmental sanitation engineering group introduced community recycling banks where residents are encouraged to leave their unwanted items in return for vouchers that are redeemable at supermarkets. Those who register for an account on WeChat, a popular instant-messaging platform, will receive reward points they can swap for goods at a rate of 50 yuan for every 350 points. If they sort their garbage into specific categories, they are given cash. Next year, the system will be extended to another 350 residential communities, covering more than 1 million residents.

The program has attracted much attention, but some experts harbor doubts about its effectiveness. Song Guojun, a professor of environmental economics at the School of Environment and Natural Resources at Renmin University of China, said that although the new system seems easy to use, it will not alleviate the basic problem of waste recycling.

While Beijing is accelerating its urban development program, the city hasn't made enough preparations to deal with recyclable waste, according to Song.

"I don't think encouraging residents to classify their garbage or establishing garbage-collection centers are the ultimate solutions," he said. "There's a missing link - collection and sorting. Beijing has long relied on migrant workers to do the job; that's an undeniable fact."

Even if residents are willing to spend time sorting their garbage into appropriate categories, there will still be a need for people to collect the waste and undertake secondary sorting.

"Recyclable waste refers to materials that can be reused or turned into environmentally friendly items," Song said. "That requires manual sorting. For instance, we assume that residents know where to discard recyclable containers, but containers splattered with sauce need to be cleaned before they can be used again. Technology doesn't help. We need laborers to do this."

Environmental quandary

Beijing's unsorted waste presents an environmental problem, because it is either buried in landfills in neighboring provinces or burned, producing noxious, often toxic fumes. These pollutants, mainly sulfur and nitrogen oxides, can reach as much as 24 times the European Union's most-stringent daily limit of 50 milligrams per square meter, according to Chen Liwen, a former researcher with the Nature University, an environmental NGO in Beijing, who has studied the city's recycling industry since 2012.

"So far, at least, garbage classification promoted in pilot communities hasn't been promising," she said. "In Beijing, garbage is discarded in the wrong place in 90 percent of communities."

She suggested the government should strike a balance between development and related issues, such as the environmental and social impact.

"The government could either train more professionals to replace the migrant workers and sort the garbage, or hire experienced migrants who have been in the industry for years," she said. "I don't know how many years it will take for Beijing to solve the recycling problem. It largely depends upon whether the government will take the steps required to fill the gap."

Sun Yuan contributed to the story.

|

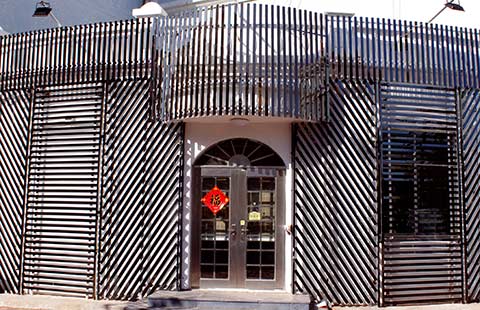

Above left: Gao, a waste collector, prepares lunch at her home in Dongxiaokou. The 48-year-old has been living in the village with her husband (right), also a waste collector, for nearly 20 years. Above right: Gao's husband disassembles old windows in front of the couple's house. |

- Premier calls for action on economic issues

- China plans gravitational wave project

- Temporary pet care poses some hitches

- Domestic violence shelter will be a refuge of safety

- New draft raises the standards for public restrooms

- Future stars will need English to shine

- Crowds flock to see Olympic venue

- Online platform facilitates legal work

- China plans more gravitational wave research

- Getting into overseas students' good books