The best gift a child can receive

By Xinhua News Agency (China Daily) Updated: 2016-02-22 08:09|

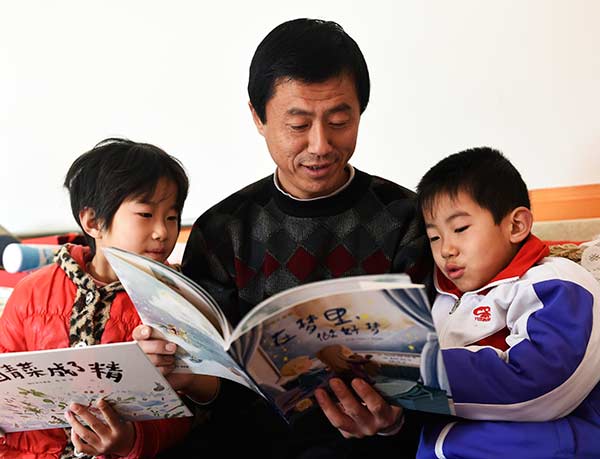

Zhao Wang reads a story to his children at their home in Shijia village, Shandong province, on Jan 27. Zhao returned home before Spring Festival for the first time in a year after working in a city far from home. Dong Naide / for China Daily |

Tragedies

In recent years, a number of tragedies have drawn attention to the plight of left-behind children.

Last year, four children, ages 5 to 13, committed suicide at their home in Bijie, Guizhou, after their parents moved away.

Bijie was also the scene of a horrific crime when a 15-year-old girl and her 13-year-old brother were killed in the family home while their parents were working in a distant province. The police discovered that the girl had been sexually assaulted before she was killed.

In 2014, 10 villagers were imprisoned for repeatedly raping and sexually assaulting a 13-year-old left-behind girl in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

Liu, from the poverty alleviation foundation, said although the cases attracted national headlines, they were quickly forgotten. "The tragedies attracted attention for a while, but became cold quickly. When the news faded, the fundamental problem still hadn't been eradicated," he said.

The scale of the problem has been underlined by surveys and reports compiled by social organizations. A report published in November by the nonprofit Lassock Care Fund of the China Social Welfare Foundation found that girls in rural areas are more vulnerable than their urban peers.

The report said left-behind girls in the country's central and western rural regions face many disadvantages, including inadequate nutrition, poor social development and mental health issues.

Nearly 10 percent live alone without guardians, while more than half stay with their grandparents. Nearly 50 percent of girls left at home have one absent parent, according to the report.

In April, a report on education, led by Zhang Liangxu, deputy director of the China Youth and Children Research Center, concluded that the structure of migrant families is likely to result in juvenile crime.

"There are important links between family factors and juvenile crime. Bad family structure, a lack of parental guidance and a poor economic and cultural environment are key factors that result in delinquent minors," the report said.

Zhang and his colleague Zhao Huijie also conducted a survey at a juvenile detention center.

They found that more than 9 percent of juvenile criminals were left-behind children, while 9 percent were children from migrant families who lived in with their parents in cities.

"The children from migrant families were unable to adapt to the new environment smoothly. When children move to cities with their migrant worker parents, they need to blend in with urban life quickly," Zhang wrote in the report. "However, some children move to the city at a young age and their parents, busy with work, do not provide enough care and attention. Young people may adapt to city life blindly and in the wrong way. On the other hand, the city is not tolerant enough to cuddle these new residents and provide appropriate support."

A high price to pay

It took Yu Changmei three months to secure a job at an electronics factory in Chongqing at a monthly salary of 1,600 yuan, almost the same as she earned in Guizhou. Tao Yonghong has not yet found a job.

Still, they say being a family once again compensates for the drop in income. "It's been worth it," Yu said. "Separation from my family and community was too great a price to pay."

However, the couple didn't return home because they had been persuaded by preferential policies or government aid. Instead, the impetus came from their children's teacher, Peng Kaiqiang, who noticed that the children were often glum and didn't seem to enjoy school parties.

"Their uncle treated them well, and their foster family did not struggle for money. What they lacked was their parents' love," said Peng, who phoned Yu and Tao every week to talk them through the children's academic performances. Eventually, Yu realized the separation was not doing her children any good.

Soon after the couple returned home, Peng saw the Tao children coming out of their shells.

"They used to follow their uncle back home in silence, but now it's all hugs and laughs when their mum or dad picks them up," Peng said.

The parents of some of the other children in the class have also returned home, and the number of left-behind children in the school has fallen to 11 from more than 30 in 2012.

In the past three years, Chongqing's left-behind population has shrunk by 16.8 percent to 890,000.

While this may be good for the children's well-being, the scale of China's migrant worker population nationwide - 247 million at the end of last year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics - means the problem will not disappear altogether.

The authorities are now ready to act on the State Council's new guideline. "Given China's economic and social development, the phenomenon (left-behind children) will persist," said Li Yi, head of children's affairs at the Chongqing Women's Federation.

"We'll help the guardians of left-behind children get up to speed with parenting skills and raise their awareness of safety," Li said. "We've already got 200,000 volunteers ready to offer care and support."

Luo Wangshu contributed to this story.

- NGO to make short film on children of HIV-positive people

- Chongqing to build Women and Children’s Hospital

- Lack of parental care is the root problem for left-behind children

- Local children will greatly benefit from learning simplified Chinese

- China launches children's chorus to preserve Tibetan epic

- Chinese scientists create functional sperm from stem cells in lab

- 2nd-child plans vex female job seekers

- Court takes case of improper detention

- Projects opening to overseas researchers

- Streamlined processes to aid top talent

- Two smog hot spots identified in Beijing by think tank

- China-led gravitational wave venture seeks global talent

- Gated communities will open 'gradually', says ministry

- Watchdog pledges to intensify scrutiny

- Court says community road rule needs legislative support