|

|

|

|

30th Anniversary Celebrations

Economic Development

New Rural Reform Efforts

Political System Reform

Changing Lifestyle

In Foreigners' Eyes

Commentary

Enterprise Stories

Newsmakers

Photo Gallery

Video and Audio

Wang Wenlan Gallery

Slideshow

Key Meetings

Key Reform Theories

Development Blueprint

Li Xing:

Teachers like Li need our support Alexis Hooi:

Going green in tough times Hong Liang:

Bold plan best option for economy Dialing a memory

By You Nuo (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-04-07 17:12

When did most Chinese have to use the public phones to contact each other, as what you can see in the black-and-white picture? Not too long ago. The picture was taken in 1988 at a fixed-line service with by roadside vendors in Beijing. About 10 years ago having a telephone line connected to one's home was a privilege comparable to driving a Mercedes Benz. At the time there were only a few such cases in a large neighborhood in Beijing.

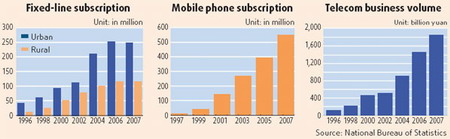

But one buys a car if they have the money, while a telephone privilege was not something one could purchase in the market, no matter what the cost. It was almost entirely dependant on one's political status and connections. One had to be an official of some sort to be entitled to a home phone. A young worker at the time might have never dreamed as a child that he'd be able to call his girlfriend from the roadside, without even getting off his bicycle. It was a remarkable convenience. That was why selling phone service was a thriving business. And a short long-distance call might earn a salesman the best sales money he could expect for the day. As late as in 1994, when a friend of mine in Hong Kong was dating his present wife in Shanghai, he said he would have to pay up to 5,000 Hong Kong dollars every month to call her, to "talk love" - as a Chinese saying goes. But he could only afford to start his talk-love session at midnight, when the charge was at its lowest rate. If history had somehow been frozen at that point, telephones, or a long distance call, could have become a financial privilege. Fortunately it has not because China has undergone enormous changes in its telecommunications industry. Long gone are the privileged phones and phone calls. Dwellers of large cities, as increasingly joined by their cousins in second- and third-tier cities and the countryside, are living in a mobile digital age. As seen in the color picture, of one of Beijing's main shopping streets, marketing campaigns for mobile handsets are among the most heated of all goods and services sectors. Nowadays, owners of the more sophisticated handsets are using their phones to play games and listen to music, to check e-mail or surf on the Web, and to read novels in bed if they suffer from insomnia. Or, in the morning, when commuting on subways or waiting for buses, some of them will start reading newspapers, or rather mobile e-papers, on their handsets. There have been a few dozen of mobile e-papers in China, the latest being the bilingual mobile e-paper launched by China Daily. Less than two months after its launch, China Daily's mobile phone edition has notched up 45,000 domestic subscribers.

|