|

|

|

|

30th Anniversary Celebrations

New Rural Reform Efforts

Political System Reform

Changing Lifestyle

In Foreigners' Eyes

Commentary

Enterprise Stories

Newsmakers

Photo Gallery

Video and Audio

Wang Wenlan Gallery

Slideshow

Key Meetings

Key Reform Theories

Development Blueprint

Hong Liang:

US should fix its own economic woes first Chen Weihua:

Need for medical privacy OP Rana:

This world dream can't be deferred Nanjie fights against all odds for a cause

By Hu Yinan (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-11-18 07:49

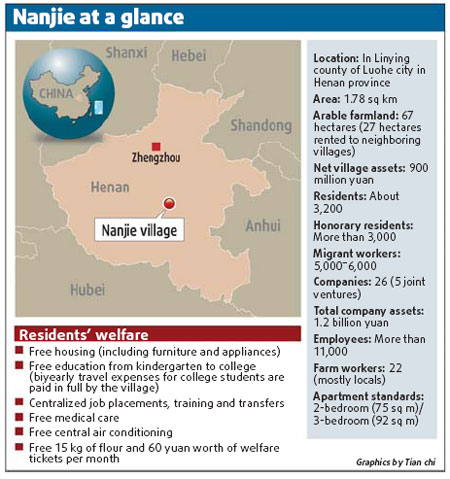

Farmers work on the land for a living, but Zhao Minsheng does so more or less for fun. He doesn't work for himself, and has no fixed land to work on or fall back upon. Despite that he has a steady monthly income of 400 yuan ($59). The 60-year-old leads a team of 22 co-workers in Nanjie, a village in the heart of Henan province. Agricultural output has soared in this village of re-collectivized farmland, though the 22 villagers, mostly men whose average age is 55, work on 600 mu (40 hectares) of land with just a pair each of corn and wheat harvesting equipment. They grow 900 kg of crop per mu and make 800,000 yuan a year. The farmers call themselves "farm workers" and work the land as a collective. The rest of the residents work in the village's 26 firms, mostly making and selling instant noodles, flour, spices, chocolate, beer, liquor and medicine. All of them give the income to the village and get free housing, healthcare, education, water, electricity and heating in return. All this makes the villagers proud, for they have "solved the problems still plaguing other villages", such as farmers' fear of lax supervision. While other villages debate how to apply the central government's new policy that encourages land-use transfer for collective farming and agricultural mechanization, Nanjie sits pretty with its successful experiment. "Collective economy is the inevitable path and the basis to solving sannong problems (farmers, villages and agriculture)," says Nanjie's Party chief Wang Hongbin. Nanjie is different from other villages. It wakes up to the tune of The East is Red at 6:15 am, greets its workers with Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman around noon and sends them home with Socialism is Good playing on the broadcast station at 5 pm. A 6-m-tall statue of Chairman Mao Zedong lords over the village center, flanked by portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, with local militia being on sentry duty round the clock. But the village embodies much more than utopian nostalgia. Thirty years into reforms, and at a time of crippling free market and rising number of rural cooperatives, Nanjie remains a leading name among the 7,000 to 10,000 Chinese villages that have held onto or readapted the collective model. Quite a few villages in Henan have copied Nanjie's model. Even leaders from Anhui province's Xiaogang village, the "birthplace of China's reform", have visited Nanjie and left words of appreciation and admiration in its museum guest book. This is what Xiaogang Party chief Shen Hao has written: "(We will) learn from Nanjie, strengthen the collective economy and proceed toward common prosperity." Nanjie is home to and provides free housing, healthcare and education to about 3,200 residents and more than 3,000 migrant workers who have been given "honorary resident" status.

Liu Gaimin's story mirrors most of her kind in the village. The 67-year-old was married into a Nanjie family in 1962, and suffered decades of hardship. She even regretted marrying there. "There was no decent thing to eat no decent water to drink and no decent place to live a heavy shower outside meant a little one inside the house," she recalls. Nanjie dismantled its communes, as did the rest of rural China, in 1983. It came under the household responsibility system, and set up two factories. But it wasn't long before the firms declared bankruptcy, and their bosses fled with the villagers' money. That's when the turning point for Nanjie came about. The village committee took over the companies' assets in 1984. Two years later, it asked people who could not use their allocated farmland to give them to the village collective so that others could work on it. Liu's family, who had one-third hectare of land, was among the first to do so. Others followed gradually. By 1990, the collective had received all of the village's 67 hectares of farmland. The village has rented out 27 hectares to neighboring villages. With the companies' assets and other property returned to the community, Nanjie began offering welfare to its residents. It started with free water and electricity, then came coal, natural gas, meat, eggs and flour, and finally education. By the early 1990s, the village had a complete welfare system, paying even agricultural taxes and medical expenses as a collective.

Work to build apartment buildings began in 1991. Liu moved into a three-bedroom apartment two years later, and worked in a factory till 2004. "I'm just an ordinary farmer. I'll be grateful all my life to the village cadre who have helped us get where we are now ... this happy life of ours didn't come easy," she says. Like all Nanjie villagers, Liu is entitled to 15 kg of flour and 60 yuan of welfare tickets a month. Though she doesn't work any more, she still earns 200-300 yuan a month for hosting field experience programs every day for the village tourism company. People began visiting Nanjie in the 1990s, but it wasn't until 2004 that the village leadership started a tourism company, charging visitors for random visits to houses and sightseeing tours. That was also the worst year for village economy. Almost every employee in the company is from outside the village. Ni Yandi, 22, from Linying county, is one of them. Long been attracted to Nanjie (the village is part of her county), she applied to work for the village after graduating from high school in 2004. The village has not only given her a job, but also allotted her a dormitory. "It's very nice working here. I don't have to think about a lot of things because most things are taken care of," she says. "Out there (outside the village), it's a messy world." To some extent, Nanjie's economy depends on the 6,000 migrant workers (excluding the 3,000 honorary residents) like Ni, many of who have settled down in the village. These migrant workers - an overwhelming number of them women - are employed mostly in the village's factories, restaurants, museum, hotel and the tourism firm. Non-Nanjie residents even hold some key posts. Sheng Ganyu, director of the weekly Nanjiecun News, is one. Having spent 12 years in Nanjie, Sheng is also responsible for dealing with the media and feels proud of his experience. "The amazing thing about Nanjie is it's home to about 600 people who have gone to or are still in college. Thirty of them have master's degrees, and one of them has a doctorate," Sheng says. "The village provides tuition fees and travel expenses for all of them, but has never forced any of them to return. People come back only if they want to; there's no obligation attached. Now, how many villages have that kind of confidence?" The Li siblings have returned for the most realistic reasons - a good pay with welfare and the comfort of staying at home. Li Chongyang graduated from Shenyang Pharmaceutical University this summer and works in the village's pharmaceutical firm for 800 yuan a month. The village paid all her tuition fees, more than 6,000 yuan in the first year and about 5,000 yuan each for the rest of the three years. "There's no place like home," Chongyang says. "All my classmates envied me the money the village gives you is like the money your parents give you And I don't feel much of a difference between here and Shenyang." Chongyang is one of the five Nanjie youths who went to Shenyang Pharmaceutical University in 2004, and all but one have returned. Her elder brother Li Yanfu, too, has returned after earning a diploma from the Beijing Printing Institute. An employee with the Sino-Japanese joint venture Naikeda color-printing firm, Yanfu got married at an annual group wedding on Oct 1. He has been allotted a new two-bedroom apartment, which he will move into soon. But unlike most senior residents, Yanfu says it depends whether he will live in the village all his life. "Right now, I'm here because there's not much pressure, and I can learn the things I would have outside the village. And I think it's time I paid something back to Nanjie." Nanjie villagers watch the standard 42 channels, including the Nanjie channel that telecasts a 30-minute program every Saturday night. Most of the villagers are Internet surfers, curious to know about the world outside as much as it is about them. Very few, though, know about the recent farmland reform. But then, the younger generation doesn't have the same sense about land as rural youngsters elsewhere. Unlike most other villages, farm workers in Nanjie aren't afraid that their children will sell the land one day if the policy allows it. Chongyang's instant reaction to the news is enlightening: "What, land? We've been working the land together forever."

(China Daily 11/18/2008 page6)

|