|

|

|

|

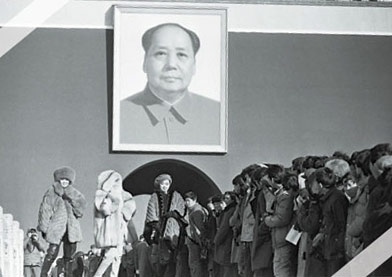

30th Anniversary Celebrations

New Rural Reform Efforts

Political System Reform

Changing Lifestyle

In Foreigners' Eyes

Commentary

Enterprise Stories

Newsmakers

Photo Gallery

Video and Audio

Wang Wenlan Gallery

Slideshow

Key Meetings

Key Reform Theories

Development Blueprint

Alexis Hooi:

How 30 years changed my view of the world Dan Steinbock:

US pushing world economy to redeflation Zhang Tuosheng:

Aso's positive signals on Sino-Japanese ties Hong Liang:

Doujhi, food of kings and commoners The way we were during past 30 years

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-12-18 08:04 How we dressed The Chinese word for "fashion" was in limbo 30 years ago, but the idea was being awakened - or reawakened. Young men liked the kind of trousers John Travolta wore in Saturday Night Fever even though nobody had heard of the movie. Bell-bottomed pants became a badge of youthful rebellion. The urge to break free of the tyrannical color scheme of blue, black and gray was palpable. Yet, like many other things, fashion liberation was achieved in fits and starts. In some cities, fashion police, armed with scissors, went on the street and cut the bell-bottoms off people's pants.

Before China's opening up and reform, Dacron and fake collars were the hallmarks of sartorial savoir-faire among the urban Chinese. Because cotton was dclass, the wrinkle-resistant polyester became the preferred fabric of a whole generation. Most people, even urbanites, could only buy new clothing once a year, usually before Chinese New Year. And like all basic commodities, fabric was rationed, which means, even if you had money you could buy only a limited amount. That gave rise to fake collars. Presumably in fashion-conscious Shanghai, where people could not stand to wear the same clothes weeks at a time, some genius invented a "fake collar". This was a misnomer because the collar was the only part of the shirt that was real. The rest of the shirt was non-existent. Since people wore it in winter, with a sweater over it, they could give the impression of more wardrobe changes without stealing their neighbors' ration coupons.

The collar went out of existence as soon as we crossed the threshold into material sufficiency. It's now become a collector's item. People born in the age of abundance can't imagine an invention like that, let alone as a "fashion item". Speaking of fashion, Pierre Cardin brought over a dozen models from Paris and staged a show in Beijing in 1979. The 1980s was marked by a sudden blossoming of bright colors, which, in retrospect, looked quite tacky as people back then had no sense of how to match colors. People just no longer wanted to be engulfed in a sea of dark colors. Surprisingly, jeans did not encounter the same ideological hurdle as bell-bottoms. My parents thought they were the same as China's "work cloth", looking sturdy and honest, instead of the fluffy and ubiquitous red and yellow. And when torn, they looked really working-class. The re-emergence of the Western suit in 1980s was another milestone. People, usually those taking official trips abroad, were given a special allowance to have suits tailor-made. When I spotted them in a crowd of hundreds in San Francisco, I could tell instantly which suit was made in China. It took a long time before those going abroad gave up these crummy suits. Nowadays, it is the trademark of a migrant worker. In the late 1980s, there was a burst of "culture shirts" - T-shirts with funny or sarcastic slogans printed on them. Its popularity ensured its demise through official pressure. Fashion trends usually start in metropolises like Shanghai and Guangzhou and then spread inland. You can gauge the distance by estimating which fashion was in vogue in the big cities. Things started to change in the 1990s. With growing migration and media penetration, the gap gradually vanished, and there's so much diversity now it's easier to guess, from what one wears, his profession rather than his background. What we listened to By any measure, Teresa Teng was a watershed, not just for pop music in China, but for cultural consciousness as a whole. Before the Taiwan chanteuse's albums became available, music on the mainland was mostly the kind you could march to. Teng showed us, more through the way she sang than through her words, that music could be about personal feelings, especially love, which had been forbidden territory.

All this was made possible by a little gadget called the cassette tape recorder. Teng's songs were never allowed on air, but people copied them, one tape at a time, and passed them on to friends and neighbors. For several years, you couldn't walk through a residential area without hearing a Teng tune wafting from one of the buildings. If Teng put sugar in our music, Cui Jian added spice. When China's own rock star burst on the scene in the late 1980s, he created an outlet for frustration. I Have Nothing, his anthem, gave voice to a whole new "lost" generation. Rock has since gained some acceptance, if not mainstream status. Today, China's army of "angry youth" is growing by leaps and bounds, but they are venting in Internet forums rather than through rock music. Karaoke, which appeared in the late 1980s as an import from Japan, caught on here in a big way. Whereas people in the West tend to be more expressive, we Chinese are taught to be reserved. We don't have a tradition of partying. That made karaoke an instant sensation. People who were normally reserved had a platform to let their hair down, so to speak. Suddenly, singing became a form of socializing, as humor is to Americans. Hong Kong and Taiwan have spearheaded the Chinese mainland's pop industry, churning out a steady diet of pop idols. Beginning in 1987, pop singers from Hong Kong and Taiwan began to perform on the mainland, so fans could actually see their idols, including Hong Kong's "Four Heavenly Kings". The talented Jay Chou (left), whose music draws on everything from popular culture at one extreme to classical Chinese at the other, also enjoys a huge following. Today, music schools have incorporated pop music into their curricula. However, singing styles, from Western opera to Chinese opera (once known as "Chinese folk"), have not changed much in the past three decades. Some new styles are emerging, such as "primitive singing", usually by ethnic minority groups without academic training. Some call these "real Chinese folk songs", but even as a group, they have yet to match the commercial success of Jay Chou. What we watched Thirty years ago, the Academy Award winner for Best Picture was The Deer Hunter. Not only was it not shown on the Chinese mainland, but few Chinese even heard of it.

The next year, Kramer vs. Kramer won the Oscar and was mentioned in the Chinese press. Pundits discussed it as if they had seen the movie. They tried to analyze the sociological implications of the story - how marriage as an institution was breaking down in the "decadent and bourgeois society". Such was the state of China's exposure, or lack of it, to entertainment from abroad 30 years ago. When the door finally opened, Western classic literature poured in. But when it came to movies and television, the culture watchdogs seemed to be overwhelmed by the possibilities, new and old. Movies produced before the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976) came out in droves for re-release, and that included many imports. The most popular was not Hamlet by Lawrence Olivier, or Jane Eyre, a 1970 version starring George C. Scott, but Awaara, an Indian movie with a theme that struck a chord with Chinese audiences. In the 1951 film, a judge loses his son, who grows up to be a thief. In the end, the father has to face the fact that the son of a judge may not be a judge, which shatters everything he believes in. In China, during the age of class struggle, one's fate was determined mostly by the social class of his or her family, which created many tragedies. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, foreign movies were devoured as if every release was a major event. People did not know when the films were originally released or how they had been received in their home countries. Occasionally, there was a "contemporary" import, such as the first installment of Rambo. But overall, what mattered was not the artistry, but the relevance to Chinese filmgoers. The very first television imports were Man from Atlantis and Garrison's Gorrilas, both little-known drama series from the US. In the first one, people could not figure out how the underwater shots were done. In the second, the idea of bad guys having fun was so novel that censors pulled it off the screen lest youngsters imitate the anti-heroes. From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, the accessibility of foreign entertainment was haphazard. More foreign countries were represented. Japanese movies and television series became very popular - but there was no guarantee of quality. Starting in 1995, China began to import foreign movies using a profit-sharing scheme and a quota system. As many as 10 so-called "big pictures" are screened every year. Most of these "big pictures" are new releases from Hollywood with eye-popping production values. Some are artistically outstanding as well, but the choice usually leans toward box-office potential. In early 1998, Titanic was released in China, and the box-office record it set has yet to be topped. The quota system is still in operation, but disks of current releases, both movies and televisions, are readily obtainable on the street or online. Meanwhile, on Chinese television stations, foreign programming has disappeared entirely from primetime. What we ate Food rationing was still in place in 1978. One would get up in the wee hours and stand in line for a thin slice of pork. Even if you had tons of money, you still ate a mostly vegetarian diet because most food items, except vegetables, required coupons. That was in the urban areas. In the countryside, meat was available only on rare occasions, such as the Chinese New Year, when households would slaughter a pig they had raised and feast for a week.

Supermarkets did not exist back then. Instead, we had farmers' markets. In the small town where I grew up, the main street doubled as a farmers' market for a few hours every morning. If you got there at 10 am there would be only rubbish left. There were still traces of the old thinking that buying and selling between individuals was "bourgeois". I remember when I was in my early teens, an egg cost 7 fen (Chinese cents) or could be exchanged for a small bag of salt. You could not find beef or bananas in my hometown in Zhejiang before I left it in 1978. In northern China, the main diet was the so-called "coarse food", meaning anything except fine-grade rice and wheat. Steamed buns made from high-quality flour were available only on special holidays. In cities, they were still rationed but available more frequently. Moreover, before the era of greenhouses, fresh vegetables were hard to come by during the barren winter season. In cities like Beijing, residents would stack heads of cabbage like wooden logs along stairways and corridors, which would become so cluttered it would be difficult to walk by with a bicycle. Dining out was often a nightmare. The wait for a table was so long even the worst food would whet your appetite. You had to pay for the meal beforehand, so you could not back out. Service was an alien concept, but the few restaurants there were would post a notice of Do's and Don'ts for service on the wall. When Coca-Cola came to China, the reaction of local youth to the taste of this soft drink was captured in the 1986 movie A Great Wall, made by Chinese-American director Peter Wang: "Yuck, it has the tang of herbal medicine!" That was exactly what many of us said. Coke was an acquired taste, to say the least. The emergence of supermarkets in the mid-1980s was something of a black comedy. Although customers were allowed to touch the merchandise before purchasing, there would be shop clerks guarding every aisle lest you ran away without paying. By the 1990s, the age of scarcity had given way to the age of abundance. Ration coupons had been phased out completely. The big irony is, what used to be considered poor man's food is now considered a healthy diet, and being fat is no longer a sign of wealth, but rather, of a lack of exercise. Regional cuisine is not regional any more because you can savor any type of food in a sizeable city, not only from different parts of China, but from the rest of the world. There is both diversity and abundance. Now that China has turned into a paradise for epicureans, fashionable young women are boasting about how little they eat! How we dated Thirty years ago, a good-looking guy would most likely sport an army jacket, sunglasses with the label still on them, and a Sanyo cassette tape recorder playing Hong Kong pop songs. To meet a girl, however, he would need a matchmaker. If he simply walked up to a girl and asked for her name - few homes had phones then - he would probably be considered a "hooligan". The dating ritual was complicated. Though marriages were no longer arranged by parents (at least not in urban areas), they still came under the jurisdiction of enthusiastic amateurs. Matchmakers - usually middle-aged women - took it upon themselves to bring their single relatives or colleagues together. A recent graduate assigned to a workplace would soon be visited by such a colleague. Typically, she would ask what qualities you were looking for in a spouse, and would then go through her mental database. Often, she would share that "database" with like-minded, female friends. Soon a candidate would pop up and a meeting would be arranged. The most likely locale for a first date would be a park, a movie theater, or a public library. The matchmaker might tag along on the first date. In any case, you would be expected to report the "result" to her. If you were satisfied, she would be happy for you; if not, she would pester you for a "reason". The most baffling answer for a matchmaker was "She's very nice, but I don't want to go out with her again." That made her job difficult. If you gave this explanation a couple of times, you would be blacklisted and would not be given any more dates. The matchmakers were good Samaritans, or busy-bodies, depending on your perspective. They were not in it for the money - a happy couple might give her a gift, but this was hardly compensation for all her effort and anxiety. Matchmakers were like Disney; they wanted to ensure "happily ever after" for everyone they knew. In those days, there were few chances to meet new people. Many people dated colleagues from work. Long-distance relationships were common, because it was hard to relocate or change jobs. The art of writing love letters flourished. Once two people clicked, they would spend years developing their relationship. A walk in the park, a chat in the living room, meeting their future in-laws and buying gifts for them dating was governed by strict rules, with little room for spontaneity. Premarital sex was taboo, and if discovered could have terrible consequences, such as losing your job. In the mid-1980s, cities like Guangzhou began to see young lovers hugging or even kissing while sitting on their bikes. In smaller places, holding hands in public still drew frowns. But Guangzhou had dance clubs and "music teahouses", a predecessor to cafes and bars. Today, all that is ancient history. With the Internet and vastly increased mobility, dating has grown much more spontaneous and efficient. The sphere of potential dates is as limitless as your MSN or QQ circle. Dating has jumped from antiquity to post-modern in just one generation.

|