New doors open for the visually impaired

Millions have wider range of products to choose from

During a break from her work in the afternoon, Yin Menglan stands up and walks slowly to a window. She cannot see the view outside, but can feel the sun's warmth.

Yin, 33, who has been a proofreader at the China Braille Press, or CBP, for 11 years, works by touching a Braille pad linked to a computer.

The computer converts regular text on her pad into Braille. Yin reads out the text, while Zhang Chuyi, a sighted person, compares what Yin has read with the text for a book, correcting any errors by using the computer.

Yin is one of more than a dozen proofreaders at CBP who help with publishing books in Braille.

In May, China officially joined the Marrakesh Treaty to Facilitate Access to Published Works for Persons Who Are Blind, Visually Impaired or Otherwise Print Disabled, or the Marrakesh Treaty in short.

The treaty requires nations that sign up to it to create limitations and exceptions to copyright law to make it easier for those with poor or no sight to access printed works in formats such as Braille.

The treaty is extremely good news for the 17 million visually impaired people in China, who now have a much wider range of products to choose from.

According to China's copyright law, Braille presses are empowered to produce Braille versions of any published book. They have to credit authors, but do not have to pay them or even inform them that such versions are being produced.

Editors have been making careful choices. Wo Shuping, deputy editor-in-chief of CBP, said: "Every year we select thousands of books from those on the market before finally deciding to publish about 1,000 of them in Braille. These books cover a wide range of topics, including politics, economics, music, health and literature."

Wo said the books editors choose are often not bestsellers, but those that help people gain a positive attitude toward life and which promote good values. "We hope our books are still worth reading decades after they are published," Wo added.

CBP's list of such publications includes National Geography for Children, which introduces China's landscape and basic geographical features; The White Seal, a short story by British author Rudyard Kipling; and China in Museums: Decoding Fossils, a book for children that explains fossils.

"We have high standards for books aimed at visually impaired people," Wo said.

Invented by blind Frenchman Louis Braille in 1824, Braille featured the 26 letters of the Roman alphabet, each represented by six dots formed in a unique way to enable blind people to read text in French by touch.

The idea was adopted by other European nations which drafted their own versions of Braille, with some minor changes.

In 1952, Huang Nai, the youngest son of China's revolutionary leader Huang Xing, drafted the country's first national Braille plan three years after losing his sight.

Combining a number of earlier local plans, Huang Nai's is based on pinyin, which enables Chinese to be spelled out in the Roman alphabet.

Wang Lili, senior publishing expert at CBP, said, "Chinese Braille is still based on Huang Nai's version, with a few changes."

In the CBP printing house, special machines click on the paper to form the Braille dots before the paper is inserted into the books.

Wang said the spaces between the six dots are important features of Braille. "The Braille characters are the same size, and space is an essential feature for blind people to recognize the character. To contain sufficient information, Braille text is extremely large," she said.

Cheng Donghao, 23, who has been reading and writing in Braille since losing his sight when he was 3, cited Blind People Monthly, a magazine affiliated to CBP.

Cheng, who lives in Beijing but whose hometown is in Henan province, said the pages in this magazine are more than 30 centimeters long, 25 cm wide, and each has about 500 Braille characters.

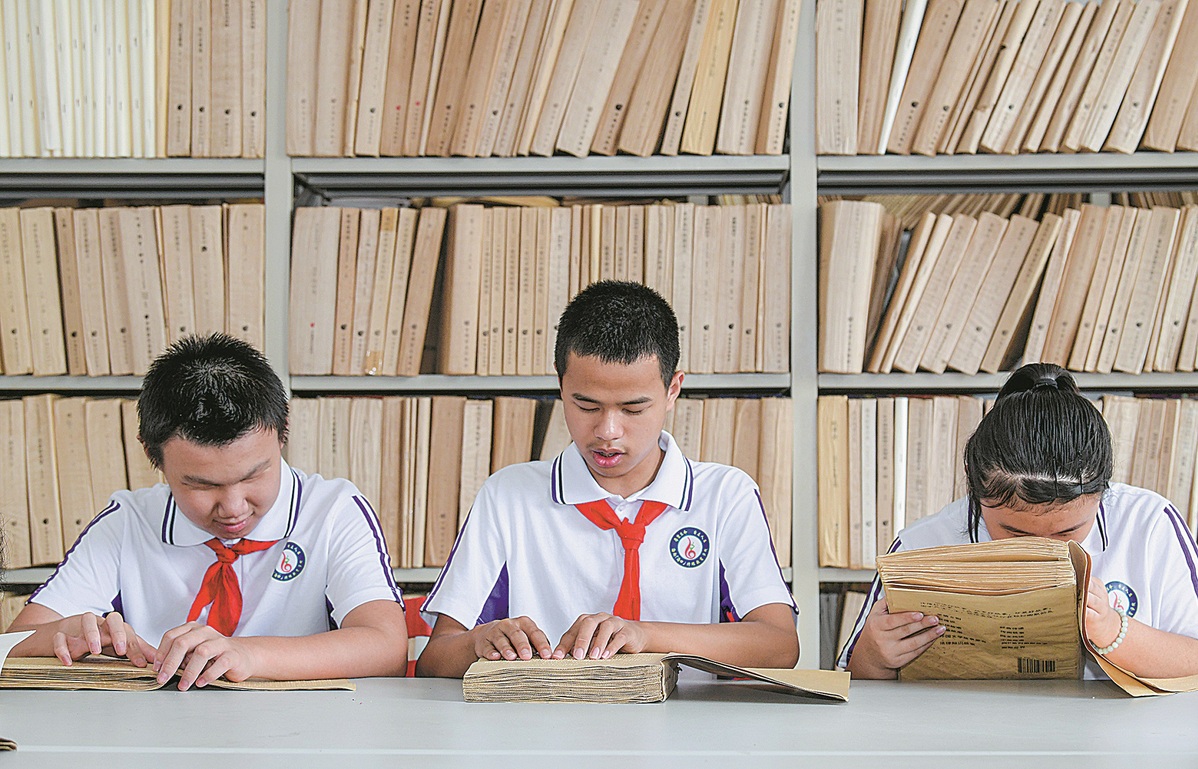

Braille text is not printed with ink, as blunt needles are used to make the dots. As a result, the pages of a Braille book are thick and they have to be bound together carefully to safeguard the dots. At the China Braille Library, some books printed in the 1960s can still be read today.

When Cheng became blind, his mother decided he should learn Braille after she first taught herself to use it. She recycled paper from a calendar, using a needle to make dots on it to form Chinese characters.

In this way, Cheng learned some 100 Chinese characters as a child. "I am deeply grateful to my mother. She made it possible for me to learn characters, and Braille turned out to be an essential channel for me to get to know the world," he said.

"Braille is our systemic language and grants us a sense of belonging."