|

|

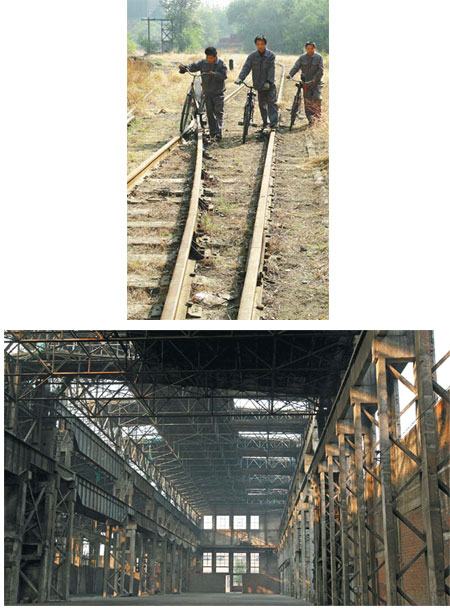

Top: Rail tracks were used to transport iron and steel at Shougang's old site. Above: The renovation of most of Shougang Corp's abandoned buildings is yet to start. Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily |

Shougang steel plant's 'iron rice bowl' was turned upside down by the factory's relocation, but the abandoned site's transformation into a cultural industry zone offers new opportunities. Zhang Yue and Pu Zhendong report in Beijing.

Liu Luguang didn't take a day off during the past National Day holiday. That's been the case for the past 20 years he has been an iron and steel worker.

But since the plant he worked in has been abandoned, he worked through this holiday at the Shougang Corp's vacated Beijing site as the electrician of the first annual Shougang Light Festival, which started in September.

It was the first time Liu had seen so many visitors since the factory shut down its last furnace in December 2010.

He says he has brought all of the passion of his old job to his new one.

"It's my first time to welcome hundreds of people to our factory," he says.

"It feels so good to see them enjoy their time here."

The 40-year-old joined the State-owned steel maker Shougang Corp in Beijing in 1990 at age 17. There was huge demand for iron and steel then, and the factory produced up to two-thirds of Shijingshan district's GDP.

"Shougang was one of Beijing's best State-owned factories," Liu says.

"A job in such a factory is what we call an 'iron rice bowl' (Chinese slang for a stable job). All we needed to do to keep it was to work hard."

Liu and most of his colleagues believed they'd work there until retirement.

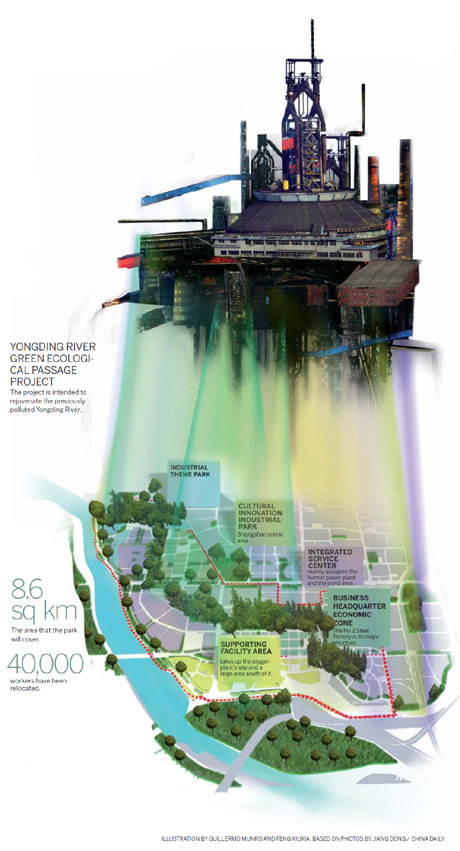

It was a massive plant - 8.6 square kilometers that spanned the corners of three districts: Mentougou, Fengtai and Shijingshan.

But discussions about relocating the plant because the pollution it created hampered the capital's development intensified in the following decades.

Shougang's publicity chief Wu Jianxin says the plant officials heard people's complaints and had been trying to reduce its environmental impact since the 1990s.

Despite Shougang's efforts, the calls for its relocation intensified. And Beijing's successful bid to host the 2008 Olympics determined the proposal's fate.

"As an iron and steel enterprise that consumes a lot of energy and produces a lot of pollution, Shougang didn't fit into Beijing's development plan," says Lu Bing, director of Peking University's Department of Urban and Regional Planning.

"Relocation and transformation had to happen."

In February 2005, the State Council approved plans to move the factory to Hebei province's Caofeidian island and reinvent the old site as a cultural industry zone.

Moving the plant to an island offered the advantage of the natural harbor that can accommodate cargo ships carrying 200,000 tons of freight.

"The factory had thought about expanding to the island during its best years in the 1990s," Wu says.

"So, Caofeidian was the best choice."

Caofeidian was then constructing new economic zones and attracting investment, which made the relocation a win-win move.

But it was challenging to relocate the plant's 40,000 workers.

Workers had three options.

"It was simple," Liu recalls.

"We could stay in iron and steel and move to Hebei, remain in Shijingshan and work at the cultural industry zone or quit and take compensation based on how many years you'd worked for Shougang."

Liu wanted to stay with his family in Shijingshan and use his skills to assist the corporation's transition.

He started his own transition by undertaking three months of cultural and creative industry training.

But it took him longer to make the shift, he says.

For decades, Liu had worn his work uniform everywhere he went, on or off duty. But he felt this was improper after completing the training.

He still feels like a steelworker, even though he hasn't done that kind of work in the nearly two years since the plant moved.

Liu still always speaks loudly and clearly, as if machines were grumbling beside him.

"It was strange to hear silence in the factory after the four major steel boilers stopped production," Liu recalls.

"I've gotten used to yelling over the machines that roared day and night over the years."

Liu takes joy in the light festival's success as the first cultural program at the plant since production ended in 2010.

Beijing resident Li Xiaolei says she was impressed by the colorful lights on the water cooling tower, impounding reservoir and steel boiler.

"It was grand and gorgeous," she says.

"I thought the iron and steel site would be ugly and gray, but it was indeed beautiful."

But while the festival marks a milestone in the plant's transformation, it still has a long way to go.

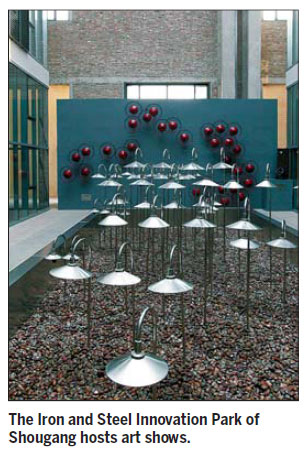

The Beijing Municipal Planning Commission's latest blueprint calls for the dissection of the plant into five functional areas, including an industrial theme park, a cultural innovation industrial park, an integrated service center, a business headquarter economic zone and a supporting facility area.

The area alongside Yongding River is set to become Beijing's largest waterfront eco-entertainment zone.

The entire zone should be completed by 2020. The first phase from 2012-15 will involve the initial land development, basic infrastructure construction and arrival of leading industry enterprises. The second phase, from 2016-20, will build the modern industrial system of Shougang's transformation.

"Reconstructing the whole site is a big project, and we've visited several old industrial areas to learn about their experiences," Liu says.

"But, personally, all I hope to do is welcome people to enjoy and appreciate Shougang. It is a historical memory for me and for the country."

Shougang remains home in the heart of Liu Chunli, who started at the plant in 1983 and has moved to work in the new factory. Many former plant workers feel the same way, he says.

"However the reconstruction goes, Shougang's east gate will hopefully stay as it is," he says.

"It has long been Shougang's signature landmark. Even though I don't work inside that gate anymore, it's still home."

Contact the writers through

zhangyue@chinadaily.com.cn.