|

Giancarlo del Monaco's Otello is a tribute to Verdi's 200th birthday, produced by the National Center for the Performing Arts. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Review | Raymond Zhou

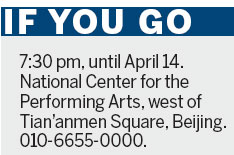

Otello is the first of two new productions the National Center for the Performing Arts is staging in Beijing to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi's birth. Nabucco will be staged in May.

NCPA has enlisted the services of Giancarlo del Monaco, whose Flying Dutchman last year wowed audiences but alienated some critics. He has again delivered a cinematic experience fit for popular sensibilities.

A stormy ocean is projected on a closed curtain, which disappears when the stage proper is lit. A turbulent sea serves as visual interlude to break up set changes and accentuate stage actions, such as the dramatic climax when Otello kills himself next to Desdemona's body and the two are engulfed by raging waters.

But there are also places this overarching motif needs to be adjusted, especially the transition into the bridal chamber duet that closes Act I, which should be amorous instead of choppy.

Del Monaco has a special affinity for Verdi's penultimate opera. His famous father, Mario del Monaco, used to sing the formidable title role.

Tenors who perform admirably in this role are a rare breed. American tenor Frank Porretta has the right baritonal timbre, but is a tad small in the size of his voice, which tends to be drowned out by the orchestra reaching a crescendo. But he is a committed actor, who throws himself into the topsy-turvy emotional state of the Lion of Venice with such conviction you soon stop nit-picking.

Like many of Verdi's works, the real star often shifts away from the title character to the opposite lead.

In this case, Zhang Liping, whose turn as Madame Butterfly in the Covent Garden production is now a 3-D tearjerker around the world, is a Desdemona to cherish - and weep for. There is not a single weak note in her performance, with limpid tone and lyrical tenderness that make victimhood achingly poignant and give relief to the evil of jealousy. Her portrayal is at once restrained and natural.

The biggest impact, both visually and emotionally, comes at the beginning of Act IV. Del Monaco stages the Willow Song under a luxuriant willow tree, which can be interpreted as either a touch of genius or a sign of insufficient imagination.

I would go for the former because so many productions of the opera simply set this act in the bedroom. The gently swinging willows are so emblematic of Desdemona's fate that it provides the perfect visual balance.

The swift scene change between the Willow Song and Ave Maria, with music uninterrupted, speaks of Del Monaco's cinematic flair and NCPA's technical wizardry.

But stagehands should take extra precaution not to make any stage noise as this is the juncture any sound of stage movements could be distracting and may jolt the audience from arguably the saddest moment in both Verdi's and Shakespeare's tragedies.

The use of two intermissions, after acts one and three, is a weird choice. A single intermission right in the middle would have done more justice to the tautness of the piece.

The set is designed by William Orlandi, with costumes by Jesus Ruiz, lighting by Vinicio Cheli and projections by Sergio Metalli.

Otello runs until April 14 and will surely come back by popular demand. Two casts in the four principal roles rotate on alternate nights.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

Giancarlo del Monaco stages the Willow Song under a luxuriant willow tree. |