Through seating and watercolors, two Beijing shows illustrate the social connotations of the spaces where we live. Lin Qi reports.

East or West, home is best. Two parallel exhibitions at the Beijing World Art Museum show the similarities and differences in how Chinese and Western interior furnishing bring dwellers comfort and security.

On the museum's first floor, visitors can appreciate the crafts of classical Chinese woodworking, especially Ming-style furniture, through the simple yet graceful lines that shape a chair. Upstairs at another venue of time and culture, people get to see the changing home decoration styles depicted in watercolor drawings of 19th-century Europe.

|

|

Classical Chinese seats in various styles are displayed in the World Art Museum in Beijing. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

The displays not only celebrate the aesthetics of interior spaces in two cultures. They also attest to the rising demand of China's nouveau riche, who desperately seek inspiration when decorating their newly bought apartments and villas.

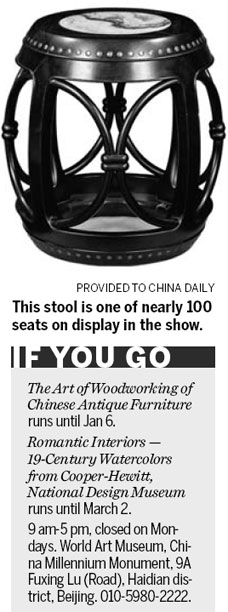

The Art of Woodworking of Chinese Antique Furniture presents its second show: nearly 100 seats in various styles spanning 1,000 years from the Liao Dynasty (916-1125) to the early 20th century. Its debut exhibition in 2012 centered around the evolution of beds.

According to its co-curator Lin Cunzhen, hidden behind the behavior of seating are profound social connotations; and seats provide the most vibrant examples of people's lives in different times and regions.

"Ancient Chinese kneeled on the ground, and with the infusion of nomadic and agricultural cultures and the introduction of Buddhism, foreign folding stools and high-legged chairs appeared in people's lives and formed the concept of 'eats'," Lin says. "The starting point of home furnishing, the seats influenced how desks, shelves, closets, beds and other furniture developed in history."

Meanwhile, seating divides a space into several areas of varying importance, and further constructs the hierarchy of ages and social statures. Lin adds that seats, which have a combination of material and spiritual meaning, have long had great cultural significance.

The folding chair stands out with mystic charms that people can get a sense of through a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) black-lacquered chair on display. Its structure is a marriage of the Han-style chair back and a campstool used by nomads of northern China at their bases. The smooth curves and delicate details are exuberant with noble touches - the folding chair was commonly used by emperors and nobles in outdoor activities and hence became a symbol of privilege.

Shanghai-based connoisseur of Chinese antique furniture Curtis Evarts devotes special attention to a well-preserved bamboo deck chair. It dates to the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and early Republic of China (1911-1949). The decorative patterns and complicated structure - a section can be stretched out and drawn back, allowing people to rest their legs - make the chair a fine example of elegance. Evarts says it could be from Guangdong province, where people rely on such chairs to avoid the summer heat, and the chairs were also found in Europe.

Indeed, people will find Chinese chairs and other Oriental-motif decorations were an important part of home furnishing in 19th-century Europe in several watercolor paintings at Romantic Interiors, the concurrent show. The exhibition displays 72 works from the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York.

Leaving their homeland, Chinese chairs and ceramics were placed in an utterly different style of interiors, which featured bold designs, flashy colors and extravagant feelings.

The Oriental-themed decoration is one of the 10 sections at the exhibition to give a glimpse into the development of the home furnishing of Europe's upper-middle class two centuries ago. The paintings demonstrate how people applied Neoclassicism, Gothic, so-called Chinese style (actually a mix of Chinese, Egyptian, Japanese and Moorish elements) and aestheticism to polish the look of their living rooms, studies, libraries and bedrooms. They were painted by professionals, amateurs and housewives, and were passed along as heirlooms and gifts.

"We want to introduce the unique brushwork and enriched contents of watercolors as a distinctive genre of art that people know little about," says World Art Museum's director Wang Limei.

The watercolors are part of a donation from Eugene V. Thaw, a US art dealer, and his wife, Clare. The exhibition is the first cooperation between a Chinese museum and a Smithsonian museum. The World Art Museum hopes to display more collections of other member museums of the Smithsonian, which is said to be the world's largest museum and research complex.

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn.