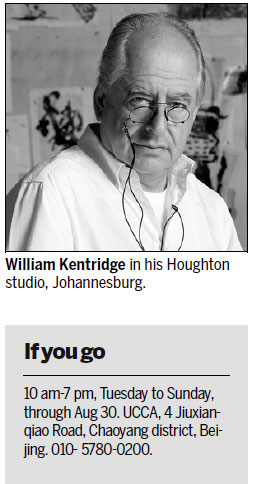

A peek into an artist's studio offers an insight into a creator's mind. In William Kentridge's Beijing exhibition, his most personal space is on display. Lin Qi reports.

The studio is an artist's castle - a place where he can play king or buffoon.

It's a safe space for "stupidity", for fun and experimentation, 60-year-old South African artist William Kentridge believes.

|

South African artist William Kentridge is holding a retrospective in Beijing, where the exhibition hall is designed like a studio (right). Highlights include Drawing for Felix in Exile (left) and Rebus (top). Photos Provided to China Daily |

"It's a place where you can become different characters and watch your different selves," he says.

"When you leave the studio, you edit yourself to go into the world."

His retrospective at Beijing's Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, William Kentridge: Notes Towards a Model Opera, reveals how he approaches artistic conjuration in his Johannesburg studio. A display of his drawings, prints and animations reveal his creative process.

Kentridge's work debuted in China halfway through his three-decade career. His film, Shadow Procession, was shown at the Shanghai Biennale 2000.

"Although Kentridge makes artworks that are intrigued by, and reflect upon, his surroundings in South Africa, his creations touch upon these issues that (people) are universally concerned with," says Philip Tinari, UCCA director and the curator of Kentridge's exhibition.

The show starts with Kentridge's charcoal and pastel drawings from the late 1980s, when he invested more energy in pure art. He had previously been active in theatrical art and television production.

The show reflects upon Kentridge's ponderings of modernization, colonialism and the passage of time. Twenty-two projectors screen the hand-drawn animated films he became internationally acclaimed for, including the Soho Eckstein series, Shadow Procession and I Am Not Me, the Horse Is Not Mine.

Kentridge also shows his video, Notes Towards a Model Opera, which he specially produced for the Beijing exhibition. He rearranges the visual elements of Chinese maps, revolutionary slogans and the "Red classic" ballet The Red Detachment of Women, in which he presents a third-party observation of modern Chinese history.

Kentridge visited Chinese cities last year to work.

"I have three different senses of China to put together," he says.

"One is of the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76), that the Party was very present in everyday life. The second is the older, rural China that had been there for centuries. The third is the contemporary China, with Beijing and Shanghai much like European cities but also unlike them in some other ways."

Viewers witness imaginative journeys through Kentridge's studio and are invited to experience the different chambers of his mind.

Some of his charcoal drawings are simply pinned on large paperboards that stand on the ground and lean against the wall. The wooden boxes for transporting his works were dissembled and used as screens upon which his noted video work The Refusal of Time is projected.

Kentridge says he is interested in the way in which people build knowledge from fragments, and he enjoys reconstructing the process in his studio.

"The studio is a miniature world. You can think of it as a physical space in which the world comes in the forms of paper cuttings, postcards, prints, e-mails, last night's dreams and a phone conversation.

"They are remade into something that becomes a drawing, a film, a lecture or a piece of theater. The studio also looks like the inside of one's head. You walk across the studio from this photograph on a wall to the letters over there to a drawing in process, and this journey looks like a sorted move from your ideas to your head.

"That process of working in the studio and making artworks becomes a demonstration of how we make sense of ourselves. It doesn't really matter what specific subject (is touched upon) but (rather) the process to show how we make our own meaning and why we can't stop making meaning."

Kentridge's works address sentiments before and after apartheid. His parents were lawyers reputed for defending apartheid victims.

On the other hand, Kentridge believes that while his parents' professions relied on logic, his requires untethering from rationality.

"Being in a studio is a way of not being logical and of resisting the demand for logic," he says.

Kentridge shared this methodology with Colombian architect-turned-artist Mateo Lopez, when they worked together as mentor and protege in Kentridge's studio. It was a yearlong program funded by the Rolex Arts Initiative.

They reflected upon the experience in a dialogue along with the Beijing exhibition.

Kentridge guided Lopez to walk out of his comfort zone of drawing with precision, and to be messy and to work with his hands, not his head.

"What I understand from our conversations is that I should try not to control things too much, try to create something from chaos," Lopez was quoted as saying.

"That is interesting."

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn