In the live music scenes of Beijing and beyond, expatriate rockers discover receptive audiences and a vibrant, anything-goes atmosphere that encourages originality and experimentation

Forget the Great Wall and forget the Forbidden City; if you really want to know what sets the Chinese capital apart, tune in now and get with the Beijing beat. If you do, you may well find that it has become one of the most exciting music scenes on the planet.

That at least is the way expatriate musicians who perform in the city are seeing and hearing things.

Maikel Liem, 36, laughs as he talks about a particularly memorable performance.

"It was in 2010 that the band the Amazing Insurance Salesmen competed in the Global Battle of the Bands in Malaysia," the Dutch bass player says.

"We represented China, and yet there was only one Chinese person in the band."

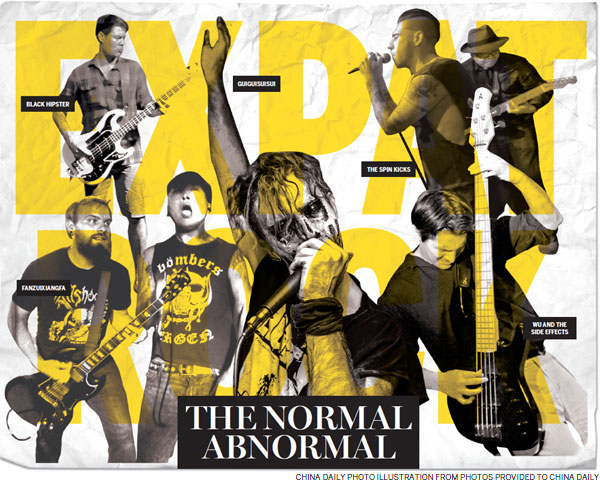

After playing at Temple Bar in Gulou, Beijing, a year ago, Amazing Insurance Salesmen disbanded, and Liem, whose day job is as a project manager at Pactera (an outsourcing company working with Microsoft), now plays in a group called Wu and the Side Effects.

Even as "the new normal" has become the cliche of choice for describing China's economic progress, "the normal abnormal" sums up his take on the local music scene.

For one thing, in the usual scheme of things, bassists take a backseat, playing second fiddle to prominent guitarists, whereas Liem is equal to the guitarist at Wu and the Side Effects.

"That's why I love making music here. You never know whether normal is normal."

So what exactly lies behind this buzzing excitement in the music scene in Beijing and elsewhere in China that has the likes of Liem so enthralled?

It may be that growing up in a cultural atmosphere that has lacked a rock music tradition, Chinese people are more readily receptive than others to rock music and the bands that play it. In addition, the lack of ground rules in the fledgling industry give it a distinctly free-and-easy, anarchic feel that seems to encourage artists to explore new types of music and to throw themselves into experimentation.

In recent years in China, as rock music has gradually seeped up from the underground into the mainstream, more and more young Chinese have formed bands that are dynamic, fresh, talented and eager to express their thoughts and channel their energy in performances in front of ever bigger audiences in bars, at music festivals and even on national television, rather than limiting themselves to the echo chamber of rehearsal studios.

Into this scene have stepped part-time musicians from the West who have come to work in China. They feel particularly free to let their creative juices flow, having come from places that demand higher standards because the rock music industry there is much more sophisticated and demanding, which tends to inhibit them and limit their opportunities to play to audiences.

Liem, who has lived in Beijing for six years, recalls the days when rock music in China was a distinctly marginal, underground pursuit. Not only was it virtually absent from national television, but this music form seemed to be almost taboo, and many of the venues that ventured to stage rock music gigs did so shrouded in secrecy. Two cases in point are Mao Live and 2kolegas, two Beijing venues widely known to early Chinese rock aficionados, the former being little more than a metal box without windows, and the latter being, for most people, out of sight, out of mind and out of earshot.

"But last year I saw a punk band, Brain Failure, on CCTV," Liem says, "It was awesome. Things really are changing."

Josh Feola's take on the changes in rock music in China is slightly different. Feola, 28, a drummer in several bands and a freelance writer for music magazines and websites, says many young bands are now piggybacking on Chinese bands that have preceded them, imitating their style and throwing their own stylistic touches into the mix.

"It's good because five to 10 years ago a Chinese band would imitate a band from the West. Now they're imitating older Chinese bands. Sometimes it's no good if it's complete imitation. But it's good that there is a local example. I think that's healthy in the long run for the music scene."

On a rainy night in mid July, Black Hipster, a blues band, debuted at the Temple Bar. The lead singer is half Spanish and half American, the bass player comes from Australia, the drummer from Azerbaijan and the guitarist from England.

"Today is the day for new bands," said Pink Li, 28, Temple Bar's manager, wearing a camisole, a black punk-style necklace and hot pants.

"That's what we have set Wednesday aside for. After all, all bands, no matter how successful they eventually become, need to start somewhere, and we want to give them a chance to play in front of audiences."

The members of Black Hipster, well out of their 20s and 30s, have played in a lot of bands over the years, and their latest group is less than nine months old. They jumped at the chance to play at the Temple Bar, having played in many other venues, after coming across Li's contact details on the Internet.

"I listened to a demo and felt OK, so I agreed. Why not? We make money from drink, not music. We don't charge bands to perform here. If they are good, they can come back. The Black Hipsters are good."

Dann Gaymer, 28, from Britain, and his girlfriend, have formed a duo called Guiguisuisui (which means sneaky) that plays zombie music.

Performing in China is a lot cheaper than it is in Britain, Gaymer says.

"In Britain you often have to bring all your own (equipment) such as amps and microphones. In some cases you might even need to pay to play."

The fast-changing nature of the industry, and its economic imperatives and pressures have been evident this month as Temple Bar celebrated the fourth anniversary of its opening even as an experimental music bar called XP shut down not long after celebrating its third anniversary. The venue 2kolegas and another called CD Blues suffered a similar fate in 2014.

XP, meaning experimental, opened on May Day in 2012 after the founder, Michael Pettis, closed the rock music club D-22 in Wudaokou, Beijing. XP's raison d'etre was to provide a space for interesting experimental music for local Chinese bands.

Nevin Domer, 34, XP's manager, is an experimental musician from the US who plays hardcore punk in several bands. Domer, a black stud on his left ear and two black rings on his lower lip, speaks quietly, slowly and deliberately, with a mellow American accent, but he will not reveal reasons for XP's closure.

There has been speculation that beyond financial problems, the bar, located in an ancient hutong, had few fans among its neighbors, who would have been captive audiences to the raucous music that experimental bands are wont to play, and many are likely to have been unimpressed by its patrons' after-show antics outside the venue.

Domer, who has lived in Beijing for 10 years, says that before XP opened, he worked at a club called D-22, and he now works for a music label called Maybe Mars, helps bands tour and runs a small music label called Genjing (rootstock) Records. In his time in Beijing, he says, changes in China's music scene have been exciting to watch.

"Even in just the past two years things have changed a lot in every respect."

In 2005 there were fewer venues to play in, and most were small bars, he says, and not only has the nature and size of the venues changed, but their numbers have increased greatly, too.

Record labels

In fact, the music industry in general has changed, more record labels having been set up, and with far more bands. However, China still greatly lags the United States, he says.

"In China it is much easier to put on a band because there are fewer of them," he says, sitting on a step near XP, where bands are checking sound for the venue's one of the final shows.

"In the US there are a lot of bands, and many are really good. If you want to play, you have to work really hard, and you have to be good.

"In China, especially in Beijing now, there are many venues that support bands. Even people who just start playing music or just start a band can find places to play.

XP was a little more picky, and musicians, whether Chinese or expats, had to be different and experimental. You can also find a lot of small venues in Gulou, like ... Temple Bar, where foreign musicians who play any sort of rock music can play easily."

For him, another exciting development is that local bands have improved markedly.

"Some are better than many bands around the world. The local scene of Chinese bands here now is as good as local band playing in New York, Berlin or Tokyo."

Other expatriate musicians in Beijing are just as upbeat as Domer about the industry.

Punk band

Feola, also from the US, says Beijing has become a world-class music city. Feola is a drummer in a punk band called Subs, which he joined last year. He has been in Beijing since 2009 and first joined a Chinese experimental psychedelic rock band called Chui Wan, one of his favorite local bands.

"Most music I listen to is Chinese, because I live here every day and there is enough good Chinese music about. I love a lot of music that has come from Zoomin' Night (an event XP had staged once a week.) ... Some of it is very interesting, and there are a lot of fresh ideas coming out of the Beijing music scene."

For many expatriate musicians there is great appeal in trying to fit into such a vibrant local music scene with so many distinctive bands.

Alexander Fong, 35, a page designer for China Daily, is a guitarist with a post-punk band, Zhilaohu, or Paper Tiger, that he started with an Australian workmate, Joseph Catanzaro, and a Chinese drummer.

Fong, an American-born-Chinese, says his band is trying to broaden their audience by playing original music and, on occasion, tackling Chinese music using the Western rock tradition.

"I think that's one way of being engaged with being in China in a real, respectful way."

Fong says that when he was a teenager he saw the Chinese kung fu movie Once Upon a Time in China in the US and liked the theme song Strength of Men. Now he is working on an arrangement of it for his band.

"When I heard the HK pop music version of the song I didn't think we could cover it. But when I heard a Chinese orchestra play it I realized I could arrange it for a rock band."

At the same time, Fong and his band mates name the band Paper Tiger to appeal not only to expatriates but Chinese as well.

"I am ABC (American-born Chinese). On the level, I feel like I shouldn't just be existing in an expat culture. I want to be part of what's happening broadly in China. Many bands I really admire are Chinese, so if you are just appealing to the expat audience, that's boring. A lot of great bands are operating in China now, and if you engage with music in a real way, you shouldn't be exposed to just a single audience group."

For many expatriate musicians there is great appeal in melding modern and local music traditions.

Liem says he likes the idea of playing outside in a hutong, particularly a cucurbit flute accompanied by drum and bass, or of playing the traditional Chinese two-string bowed instrument the erhu with a guitar.

"When you go to see a live show you can see a lot of mixes. It doesn't always sound good, but it's interesting and really enjoyable."

Competition

Gaymer says that in Britain competition among bands is fierce because many are trying to make a living from their music. In China it has generally been a lot easier to find venues at which to play, he says, even if in smaller cities audiences can unadventurous and are generally unschooled in the differences between different genres.

Feola says that in the US, bands play a specific style of music and there are a lot of fans of specific styles, such as hard-core punk.

"Bands can go to any city and there will be hard-core punk fans. But I haven't experienced that in China. It's more like if you make interesting music, it doesn't matter about the genre. You just find music fans.

"I found that really interesting. For me personally, it is more exciting to play in a band in China than in the US. There is more openness and more spontaneity."

Nevin Domer also brims with enthusiasm about the city that now plays venue to his music.

"For me it's enjoyable living in Beijing. The music community is different to that of other countries. ... In one way it is better because it's easier to play a show, and in one way it's not so good because the community is not developed. But in the end, it's still very interesting to do music here."

yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Fanzuixiangfa doing a vocal recording at XP. Provided to China Daily |