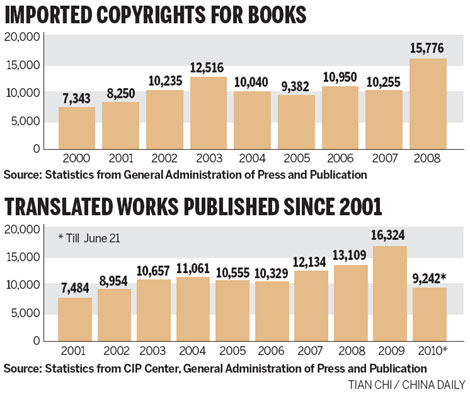

InfoGraphic

Word matters

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-06-25 10:17

|

Large Medium Small |

Translating foreign books was once like walking on egg shells with translators having to work around both 'decadent' sexual content and 'sensitive' issues. The scene is vastly changed now, Mei Jia reports

Liu Feng, editor-in-chief of Yilin Press, the country's leading publisher of translated works, recalls his senior's instructions regarding the translations of sexual descriptions in foreign books. "All descriptions of intimacy between the characters after the kiss, and reference to the human body below the neck, are to be kept out," he was told.

Novels such as Lady Chatterley's Lover and Lolita were, thus, a source of considerable headache to Liu and other editors of foreign literature.

But things are very different in the first decade of the new millennium. A complete version of Lady Chatterley's Lover in Chinese has been available since 2004, and of Lolita since 2006.

Full versions of other heavyweights, such as Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Jack Kerouac's On the Road, and some works by Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun are also now available.

Before the 1990s, foreign literature and books on social sciences could only appear on the mainland with their "sensitive" political, social and historical content exorcized.

It's a much more open environment now.

"There are fewer minefields as society develops and the government gains more confidence," says Tong Baomin, a veteran editor of 34 years at The People's Literature Publishing House. Tong and his colleagues have been involved in the publication of several translations of many significant German literary works.

"Chinese readers now have access to all kinds of books," says Gao Xing, deputy editor-in-chief of World Literature, a bimonthly magazine founded in 1953 which pioneered the introduction of foreign literature.

"Translators and publishers are now doing books whose Chinese versions were once unthinkable," Gao adds, citing Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time and Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow, as examples.

Publications of translated books in the 1950s and 60s were almost always confined to those from non-capitalist countries, with the majority coming from the former Soviet Union and East European countries. The political ideology prevalent then saw Western works as decadent and harmful, according to Zhao Wuping, vice-president of the Shanghai Translation Publishing House.

The criteria for choosing foreign works for translation were gradually relaxed with the country's opening-up and reform.

When Yilin magazine, now part of Yilin Press, published Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie in 1979, it caused a big stir, with some scholars complaining that the book failed to meet the mission of "educating the masses".

Things calmed down within a year and 400,000 copies of the book sold like hot cakes in just a few months.

Yilin's former president Li Jingrui discussed the phenomenon in an article: "Luckily, it happened at the start of the reform and opening-up, in a climate that was more open and liberated."

In the 1980s, many Western classics were introduced, Zhao Wuping says. They were classified in different series, one of which was named "Walking Toward the World", in an attempt to capture the nation's eagerness to make up for the losses of seclusion caused by political movements.

Since the 1990s, translated books from a wider range of sources have appeared, including more contemporary and popular ones.

"Now we translate and publish anything except for those threatening State interests," says Tong.

He says he recently abandoned the translation of a Korean novel that gave a false account of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Instead, he worked on a translation of how Shanghai sheltered Jews during World War II. The book includes a discussion of the military triumph of Chiang Kai-shek in the Northern Expedition War (1926-27), a mention of which, decades ago, would have been strictly forbidden.

Yilin Press' Editor-in-Chief Liu Feng also cites the publication of John Rawls's Political Liberalism in Chinese in 2000 as an example of official open-mindedness.

"Upon its publication, many people complained to the central government about the book's 'ideological inadequacy'. We prepared a written defense. However, the book survived and even became a market success," Liu recalls.

In 1992, China joined the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention.

"Translated books are now unlikely to be revised by translators or editors arbitrarily," Liu says. But he also argues that there is a case for legitimate revisions in translation to suit the reading habits of the target audience. "There shouldn't be too much fuss with unavoidable changes for better acceptance. I know that this happens with some English translations of books in other languages. Lulu Wang, the Netherlands' best-selling author, loses many segments in the English translation of her books in Dutch, after adjustments to the English readers' reading habits."

The increasing access to information worldwide has also given an impetus to the publishing of translated works.

Ouyang Tao, an editor of translated foreign books with The People's Literature Publishing House, says that with more people traveling abroad, books that might otherwise be overlooked, are getting translated.

Zhao, of the Shanghai Translation Publishing House, credits the Internet with making people more curious about the world, especially since 2000.

"Readers expect swifter action from publishers to introduce important works published abroad," Zhao says. "Besides, many Chinese read foreign works in their original languages. There's no point in hiding anything from readers in translation."

In 2003, Yilin Press took the hint from some informed readers and published Douglas Reeman's Band of Brothers months before its TV adaptation hit the mainland. This is just one of the successes Chinese publishers have had in capitalizing on the global market for popular works.

In 2006, the country's translators achieved a major triumph: They finished the full-text translation of the Mahabharata from Sanskrit. The ancient Indian epic has only one other full-text translation in English.

"It can only be achieved in a time like this," says Huang Yiting, a Sanskrit-literature research assistant with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, "when funding and translators are ready".

Tong, of The People's Literature Publishing House, recalls that when he first set out, typesetting techniques were very primitive. Each page of a book had to be typeset separately. It took months to print a collection of the Russian writer Maxim Gorky.

The technical advancements and the growing ranks of professional translators have both contributed to the appearance of many previously unthinkable foreign works in Chinese, Tong says.

Statistics from the National Library of China show that 107,500 kinds of foreign books were translated and published between 1995 and 2004. Yilin Press alone publishes more than 100 fresh translations on average each year, Liu says.

"Now we're in an unprecedented era of abundance and freedom, and face multiple choices in reading," says Ouyang.