Migrants find it hard to keep their city jobs after age 40

By Zhang Zhouxiang (China Daily) Updated: 2012-07-14 08:02

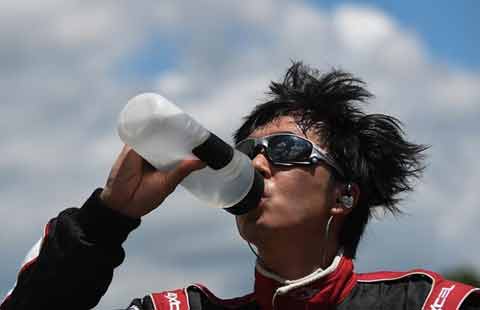

For labor-intensive enterprises in China, the shortage of labor, which has been noticeable for a few years, continues to be a headache. But at the same time many migrant workers in their 40s and 50s are finding it increasingly difficult to get a job.

A typical example is Zhao Zhongwei from Shandong province, who had to hide his real age to keep his job as a repairman.

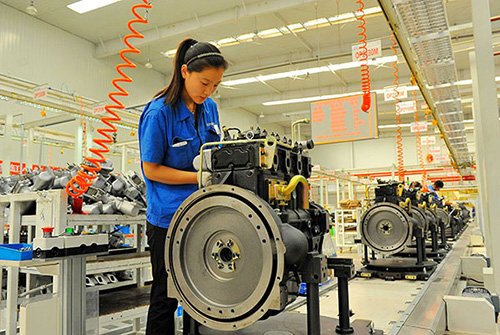

The problem is a high percentage of China's labor force has reached the middle age now, but manufacturing does not favor these migrant workers as the performance of manual laborers declines with age, said Zhang Zheng, a researcher with the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University.

Having analyzed official statistics, Zhang found that the number of migrant workers grew from 242.23 million in 2010 to 252.78 million in 2011, but those aged below 40 only increased by 2.59 million. Of those aged 40 and above, 6.83 million are "local workers", who have returned to work in their rural hometowns.

The majority of middle-aged migrant workers are the main breadwinners for their families, even though their pay tends to decrease as they grow older, said Zhang.

Many older workers from rural areas go back to their hometowns where they do lighter work for less pay, but where the living costs are lower and they can be with their families, said Zhang. In other words, migrant workers have contributed the prime of their lives to the cities, but cannot afford to stay there when they become middle aged. Having contributed much to the construction of cities, these migrant workers cannot enjoy the benefits and social welfare brought by urbanization.

China will face a more serious labor shortage if the practice of discarding migrant workers when they are past their "golden age" continues as the proportion of young migrant workers in the labor force is falling.

Zhang found that before 2004, when there was still a plentiful supply of labor, workers below 35 accounted for around 60 percent of the total migrant workforce. But the percentage had dropped to 58.4 in 2009.

"The number of workers aged 35 and below is declining, while the pool of older workers is growing," said Zhang. This tendency has raised the average age of migrant workers from 34 to 36, according to the 2011 Migrant Workers Monitor Report.

Yet instead of accepting older workers, many enterprises have moved their manufacturing plants into inland provinces or other countries in Southeast Asia in search of a younger labor force.

To solve this problem, Zhang thinks it necessary to raise migrant workers' wages, so that they can afford a home in the city when they grow old.

He cited an example to show how difficult it can be for migrant workers: During the 2008 financial crisis, many plants in Dongguan, Guangdong province, had to cut their workforce, but they did not dismiss their senior migrant workers so as to avoid paying them compensation. Instead they simply cut their overtime. Many migrant workers rely on working additional hours to earn enough money to make ends meet.

In the long run what China needs to do is improve the quality and skills of its workers, and upgrade its industry, Ye Tan, an economic commentator and columnist, wrote in her latest column. "China needs skilled workers, not basic laborers, so it doesn't remain a manufacturing plant forever."

As long as the workers have nothing but physical strength to offer, they will always face the risk of unemployment as they get older.

The author is a reporter with China Daily. E-mail: zhangzhouxiang@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 07/14/2012 page5)

- Chinese official calls for pragmatic cooperation in Belt and Road Initiative

- Asia medical tours pack in peace, fun for families seeking treatments

- Pros and cons of tapping specialists abroad

- Jinqiao denies MoU with Tesla

- Wal-Mart resets strategy with new partnership with JD.com

- The affluent Chinese cross seas for health

- E-industrial park links Poland to China's wares

- Schneider to invest in more Chinese high-tech SMEs