Robots pose new challenges to markets

By Hong Liang (China Daily) Updated: 2012-09-03 08:12

Chinese mainland manufacturers having a handful in coping with dwindling orders and swelling inventories should spare a thought for a less immediate but more far-reaching threat lying ahead.

The fast pace of industrialization that has benefited so many people on the mainland in the past several decades was largely built on the plentiful supply of land and labor. Indeed, the contributions of many millions of hard-working and disciplined migrant workers to economic growth are widely recognized.

Despite rising competition from other emerging markets, the mainland has remained the manufacturing base of choice for many multinational enterprises. But even at the best of times before the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2008, economic planners were urging domestic manufacturers to move up the value-add ladder, warning that the existing model of growth could not last forever.

The initial impact of the downturn in overseas demand on the economy was largely grossed over by the government's heroic stimulation program, which provided an opportunity for factory owners in the industrial heartlands of the Yangtze River Delta region and Pearl River Delta region to make even bigger profits by investing their accumulated capitals in real estate and some other assets.

The resulting flood of money into the real estate markets around the country pushed property prices to levels that fewer and fewer prospective home buyers could afford, prompting the government to clamp down on speculative excesses.

Meanwhile, overseas demand has continued to slide, thanks to the nagging sovereign debt crisis in Europe and sputtering economic recovery in the United States. Some factory owners have simply shut down their operations to avoid further losses. Others are shifting their sales focus to the domestic market to run down inventories while waiting for better times to return.

Looking further ahead, there is a bigger potential challenge waiting. Thanks to the advance in robotic technology robots are becoming more cost-effective than humans in an increasing number of manufacturing jobs.

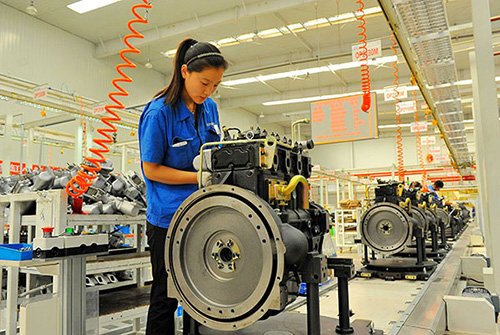

Robots are already widely used in auto factories, aircraft assembly plants and other heavy industry facilities. But only recently have they been successfully built and programmed to do more delicate and precise assembly jobs that are commonly done by young workers.

A story in The New York Times said Philips Electronics has built a factory in Drachten, the Netherlands, where 128 robots are doing the same work as efficiently as hundreds of young workers do in a sister factory in Zhuhai in China's Guangdong province. Robots, of course, don't need breaks nor do they have to make the long trek home for family reunion every year during Spring Festival.

To be sure, it will be some time before we see a large-scale replacement of humans by robots in the assembly lines. But many union leaders and economists in the West are already weighing the social cost of what is widely expected to be a new industrial revolution in terms of lost jobs.

The impact on the developed economies may not be that significant because most of the jobs that are likely to be taken over by robots have already been moved to the emerging markets in Asia and elsewhere. The wider use of robots may make it more economical for US and European companies to bring those jobs back to their home countries to save logistics and transportation costs.

This, in turn, could set off the irreversible decline in globalization, making it all the more important for mainland enterprises to strengthen their competitiveness in technology innovation and product design.

China enjoys the advantage of having a domestic market with a large potential for further development. The surest way of tapping it is to produce quality and well-designed products that domestic consumers want to buy.

- Top economic planner dismisses massive job loss fears

- State Grid pushes for 'global energy Internet'

- Foreign companies bet on China's consumers

- Chinese shares stage mixed performance, real estate gains

- ChemChina makes $43b takeover bid for Syngenta

- Shanghai Disneyland to offer cheaper entry

- Diageo's baijiu brand Shui Jing Fang helps lift its spirits in China

- ESPN joins hands with Tencent to offer sports