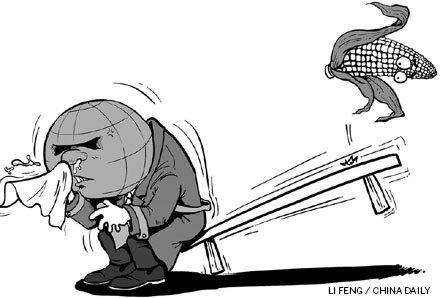

Rising food prices haunt our future

By Derk Byvanck (China Daily) Updated: 2012-10-16 08:05

Food prices in China may be relatively insulated from the volatile global food market and thus the country can ensure food security. But the country could become vulnerable to outside shocks in the future.

Oxfam's research on extreme weather and extreme food prices shows how a drought in the United States (similar to one this year) in 2030 could temporarily raise the prices of corn and wheat in China by 76 and 55 percent.

Mindful of this year's drought in the US, the most severe in more than half a century and the kind of event predicted to occur more frequently, the Oxfam research, based on modeling by the reputable Institute of Development Studies, forecasts a similar US drought in 2030 and calculates temporary price fluctuations. It has found that even under a conservative situation, a drought in the US in 2030 could temporarily raise the price of corn by as much as 140 percent above average, which is already likely to be double today's prices.

These fluctuations would occur in addition to predicted average price increases because of the impact of climate change on agriculture productivity. China will be a significant grain importer by 2030. Food prices in China will become increasingly vulnerable to price shocks driven by extreme weather in major crop exporting regions. More extreme weather is projected for regions exporting wheat (that is, the US) and rice (that is, East Asia, the US and India).

Food prices more often than not determine whether people get enough to eat, especially the poorest who spend 75 percent of their income on food. After decades of success of the global fight against hunger, the global food crisis of 2007-08 pushed back tens, even hundreds of millions of people into hunger and poverty. Since the 2007-08 crisis, the global number of chronically undernourished people has not been decreasing.

Now, almost 870 million people go hungry every day across the world according to revised UN figures published last week. China has been very successful in its fight against hunger, but it still has about 130 million undernourished people, according to a report of the UN Food and Agricultural Organization of 2011.

Hunger is a complex issue. Globally, most people who don't have enough to eat are small farmers, the very people who produce our food. On average one in every eight people went hungry for over a year in the period 2010-2012, although the world produces enough food to feed all. These people don't get enough to eat while global food companies make huge profits. Worse, one-third of the food produced is lost or wasted, according to another FAO report.

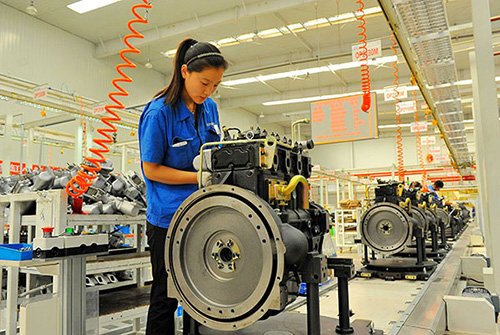

Current food production uses water, land and the ecosystem irresponsibly. As population grows and our diets change, the Earth's natural resources become scarce. Some countries already face a dangerous dearth of resources. China, for example, feeds 20 percent of the world's population with just 6.5 percent of the planet's fresh water and 7.9 percent of its arable land.

Last year, Oxfam forecast that global corn prices would double in 20 years, half of which would be a consequence of climate change. It is happening.

As greenhouse gas emissions continue to soar, extreme weather across the world provides a glimpse of our future food system in a warming world. Our planet is heading for average global warming of 2.5 - 5 degrees this century. It is time to face up to what this means to feeding millions of people on our planet. Governments must act now to slash rising greenhouse gas emissions, reverse decades of under-investment in small-scale agriculture, especially in poor countries, and provide the additional funds needed to help poor farmers adapt to climate change.

The author is economic justice manager of Policy and Campaign Unit, Oxfam Hong Kong.

- Top European e-commerce sites take part in Chinese expo

- GA8 slated as milestone, for China's self-developed cars

- February inflation lower than market expectation

- China's rail freight volume down 9.4%

- Jack Ma toasts wine with Italy's prime minister

- GAC Motor sales jump 63%, outperforming peers

- COSCO buys stake in big Greek port

- Transparency issue cited in Anbang's Starwood exit