Rethinking innovation for a recovery

Updated: 2011-07-15 10:51

By Eden Yin and Peter J. Williamson (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||||

|

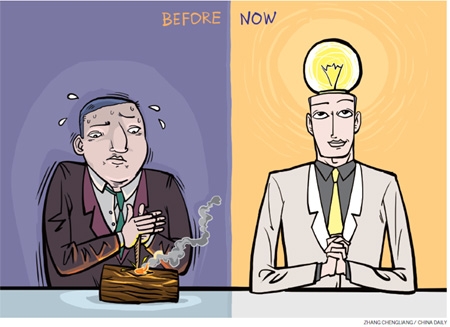

As we look at growing out of recession, innovation is more important than ever. However, the types of innovation companies pursue need to change. Managers wanting to learn how to make this change will find that China is a good place to look.

This may seem paradoxical given that, in the minds of many, China stands for imitation rather than innovation. And it is true that few cutting-edge, break-through technologies have emerged from China in recent decades. But that is exactly the point: faced with scarce resources and a highly competitive market of ruthlessly value-conscious consumers, Chinese firms have, by necessity, become adept at the kinds of innovation well-attuned to the next round of global competition, in which "value-for-money" segments will be key to driving growth.

To thrive in a prolonged, severe recession we have to broaden our definition of innovation beyond one of delivering novelty that sees the customer pay more. In this regard, we observed the three most common types of innovation in Chinese firms.

First was cost innovation: reengineering the cost structure in novel ways to offer customers adequate quality and similar or higher value for less cost. Second was application innovation: finding innovative applications for existing technologies or products. Third was business model innovation: the well-worn idea of changing one of the four core components of the business model (customer value proposition, profit formula, key resources or new processes) but with a twist - adjusting those aspects that can be changed quickly and at minimal cost.

Cost innovation involves creative ways of re-engineering products or processes to eliminate things that don't add value (or value that consumers are willing to pay for).

Take the example of Chinese battery maker, BYD. Seeing that the high cost of lithium ion (Li-Ion) batteries (at the time costing $40 a piece) was preventing their use in mainstream products, they focused their innovation efforts on reducing costs. Their R&D tried to find a way to replace some of the most expensive materials used in Li-Ion rechargeable batteries with cheaper substitutes, without compromising performance.

BYD also worked on re-engineering the production process. It figured out how to make batteries at ambient temperature and humidity, avoiding the necessity to construct and maintain expensive "dry rooms" in the plant. These moves resulted in costs falling 45 percent, taking the cost for each battery down to just $12.

These advances resulted in a value-for-money revolution that saw Li-Ion batteries replace their lower-performance nickel cadmium (NiCad) predecessors in volume applications. As BYD hopped from volume segment to segment, costs fell further, allowing it to notch up global battery market shares of 75 percent in cordless phones, 38 percent in toys, 30 percent in power tools, and 28 percent in mobile phones.

Guangzhou Cranes Corporation (GCC) followed a similar path, focusing its innovation this time on eliminating redundancy in its products and removing unnecessary steps from the production process. Prevailing industry practice, for example, was to secure metal joints by welding both sides of adjoining plates. GCC focused its R&D and engineering staff on redesigning the joints so that equivalent strength could be achieved with a single weld, thereby cutting both cost and production time (a critical consideration for buyers often faced with tight construction schedules).

Application innovation refers to innovation that is new in terms of its application, but not its technology. In other words, it involves creating a new application for an existing product or technology.

The classic example is the humble sandwich: neither the bread, nor the meat filling was new. Instead, the great innovation, credited to John Montagu 4th Earl of Sandwich back in the 18th century, was in combining the bread and the meat. In many companies, such re-purposing wouldn't be graced with the term "innovation" at all. But let's not forget that, because they rely on proven technology, application innovations often require less investment and generate faster payoffs compared with entirely new inventions.

By contrast, lateral thinking seemed to come naturally to many of the Chinese companies we studied - perhaps because Chinese philosophy starts from a view of the world as an interconnected whole, focusing more on similarities, connections and relations rather than on differences, division and the idiosyncrasies of its component parts. As a result, application innovation was more common and more highly valued among Chinese corporate innovators.

This kind of thinking was behind the application innovation that has helped Antas Chemical Company in China's Guangdong province rapidly win share in the market for sealants used in the construction industry. Builders have traditionally used acrylic acid-based products to seal the frames of exterior doors and windows. These products are reliable once dry, but if rain hits the construction site within the first 24 hours after acrylics have been applied their performance is substantially impaired. Using an alternative, high-cost silicone, in critical applications, typically solved this problem.

Antas wasn't a supplier to the building industry but it was well established in the business of selling the sealants used in shipping containers - a highly demanding environment for waterproofing. Its butane-based sealants not only offered better long-term performance and were waterproof the instant they were applied, but they also had lower production costs.

Their innovative idea of reformulating and repackaging the butane-technology sealants for easy use in the construction industry may look obvious, but it only looks so in hindsight. But because the supply chains for these user industries had remained as proverbial silos, no one had seen the potential before Antas made the leap.

Some of the world's most profitable innovations have stemmed from novel ideas that didn't involve changes in the underlying technologies, products or services at all. Instead, they involved innovative redesign of the business model, which created value and delivered it to customers.

Our research in China reminded us that rather than turning an organization upside down, fewer simple and well-targeted innovations in the way things are done can actually revolutionize a company's business model, and with it, profitability.

Take the case of Tencent, the Chinese company that runs the country's largest social networking and instant messaging service. Over the past decade Tencent built its core business with the simple idea of allowing subscribers to route short messages from their computers directly to the mobile phones of China Mobile's customers for a fee of 10 yuan (1.1 euros) per month. The service was immensely popular: Tencent's customer base grew to almost 500 million active accounts. Then came Tencent's next business model innovation: it used its links between PC's and the mobile network to allow its customers to play online games for free. By eliminating the need to download the software onto a gaming console, the problem of counterfeiting that had dissuaded many of its US and Japanese rivals from entering the market simply disappeared. And the profit model?

Tencent collected revenue from exploding number of gamers by selling them digital add-ons such as virtual weapons. It now sells virtual extras ranging from digital wallpaper to picture frames to augment all its base services. Tencent's revenue is growing at 60 percent per annum and its market capitalization now exceeds $37 billion.

It's not only in hot digital businesses, however, that a focus on coming up with simple but powerful business-model innovations is transforming profitability. We also observed this phenomenon in the more mundane business of industrial paint. Recall the application innovator, Antas Chemical, which deployed waterproof adhesive technology from shipping containers in the building industry.

The paints division of Antas has also been an innovator - this time by introducing a novel business model. When they visited industrial customers, the company's sales representatives started regularly receiving requests to set up a recycling system to remove the mounting piles of empty cans taking up valuable space at the end of their production lines. The problem was that Antas could not see how to make the recycling of cans pay. Their solution turned out to be even simpler: re-engineer the business model by installing tanks at the customers' sites, take over the responsibility for their timely cleaning, and re-supply with new colors to satisfy customers' changing production runs.

Eden Yin is university lecturer in marketing at the Judge Business School, University of Cambridge. Peter Williamson is professor of International Management at the Judge Business School, University of Cambridge.

- China to change foreign trade growth pattern

- Riches from Russia with love

- Milk price hikes leave many feeling sour

- Auction to boost China's shale gas exploration

- CSRC calls for 'rational investment'

- Ceramic makers seek legal aid

- NPLs will continue to rise in 2012: Analysts

- Housing prices continue to decline