Cloud of hurting companies has a silver lining

By Siva Sankar (China Daily) Updated: 2016-03-23 07:48

|

|

A Chinese technician displays textile equipment at an international exhibition in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, which attracted 125 companies from Vietnam, China, Japan and South Korea. [Photo/Xinhua] |

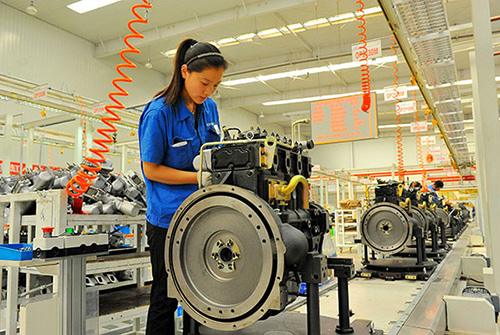

Tianneng's decision wouldn't surprise China's auto industry and ancillary players, many of whom are based south of the Yangtze River. Hurt by rising costs like wages, they are eager to either set up new plants in ASEAN countries, mainly Vietnam, or relocate altogether, by coasting on the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement.

According to one expert, the trend should not alarm China. It is, nevertheless, strong enough to warrant PowerPoint-backed talks over executive breakfasts at five-star hotels in Beijing.

I recently attended one such talk organized by the German, British, French and Swedish chambers of commerce. The audience included executives from small and medium-sized foreign firms, a contrast to mega corporations that rely on in-house experts like economists to make sense of the Western media's gloom-and-doom discourse on China's economic slowdown.

The ACFTA, as part of a larger "mess" of ever increasing, overlapping FTAs, is a hot topic.

The audience wanted to know: Is it time to relocate from China to ASEAN countries?

A female official of the Liuzhou New and High-Tech Industrial Development Zone in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, bemoaned that in spite of preferential policies, auto supplier companies are leaving in droves for Vietnam. Why? Can something be done to stop the exodus?

The speaker, Fabian Knopf, head of the German Desk at Dezan Shira & Associates, a global business consulting and financial advisory firm, didn't proffer facile answers. But he is convinced the China-ASEAN dynamic may not be a bad thing for Chinese businesses.

Regional division of labor, he said, could help all as each market will get to specialize in one business function - R&D, components or logistics. Other positives include an opportunity for China to pressure Chinese and foreign companies alike to shift light manufacturing away and make way for high-end manufacturing.

This shift has already happened in textiles, he said. "Perhaps countries like Vietnam and Cambodia might be interested in taking some of the old manufacturing from China. And companies in China, hurt by rising labor costs, could also use it as an opportunity to invest in staff development and improve productivity to reduce costs."

The rise of ASEAN as a cheaper manufacturing and services alternative should not cause concern to China, he assured. ASEAN countries may have lower costs and consumer markets larger than Europe and parts of the United States, but their infrastructure is not comparable to China's, not only in terms of "bridges, roads and railways" but "supplier networks, consumer networks, logistics", individuals' skills and industry's skills.

So, only certain sectors may feel compelled to leave China. "We are busier advising existing companies on compliance in China than bringing in new companies to China. That shows companies are hiring external experts on compliance. They want to be above board, they value being here, they want to be here and further develop."

Knopf's advice for businesses is simple: "Continue to understand China, which remains a very dynamic market. It's not enough if you understood yesterday's China. You need to be on your toes because it's not going to get easier."

Western and Central China, particularly provincial-level capitals in those regions, might further open up and present new opportunities for foreign companies in China, he said. "Smaller companies need to be nimble and flexible, and think in terms of not only five-year strategic plans but much shorter timeframes."

Both companies and the government could take some measures to ensure the situation would benefit all, he said.

Rising costs could spur companies to get engineers to develop new products and get higher margins. Instead of blindly assuming FTA benefits and tax incentives, companies must consider issues like factors of production, whether they would get the necessary staff, access to resources and customers in ASEAN countries, he said.

China should ensure young graduates from universities and vocational institutes meet the needs of industry. Transparency and clear guidelines could also help. "Companies don't really care about tax rates, which are just a variable. But uncertainty on applicable tax rates and customs rules is bad for business," Knopf said.

- Service industry displays its capabilities at intl fair

- Govt plans platforms to bring manufacturing and internet together

- China, Italy hold forum to promote cooperation

- Uruguay debuts first Chinese-built electric bus

- Shanghai index tumbles on liquidity withdrawal

- Canton Fair data fuels export optimism

- VW China's environmental program big hit in Urumqi

- Beijing puts restriction on property buyers in Tongzhou district