Rise of health startups powers nation's innovation

(Agencies) Updated: 2016-06-27 11:22

|

|

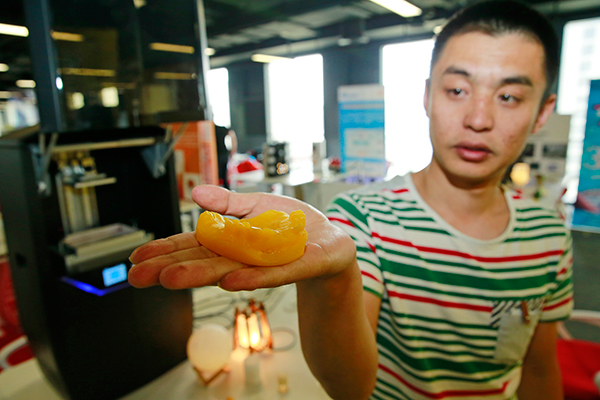

A man shows a set of artificial teeth made with 3D printing technology in Tianjin. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Holed up in a shiny glass building in the Chinese city of Chengdu, Y. James Kang spends his days researching ways to repair damaged hearts, livers and brains-with the help of stem cells and 3D printers.

The Chinese-born and US-trained biologist set up his healthcare startup, Revotek, in this southwestern city in 2014. At the time, he was attracted by the region's rich local supply of monkeys that were ideal for testing human treatments. In Chengdu, the company has drawn 215 million yuan ($33 million) in funding from a local real-estate company seeking to diversify.

A few miles from Kang's lab, AllTech Medical Systems has developed and is selling MRI systems intended to compete with multinational giants such as General Electric Co, Royal Philips NV and Siemens AG, which have dominated the market. Its MIT-trained founder, Zou Xueming, chose Chengdu to start his second company after selling his Cleveland-based startup to GE in 2002. AllTech hopes to submit an application to go public by the end of next year, with Zou planning to raise $50 million to $100 million.

They are among a string of local businesses that stand to benefit from a push by the Chinese city to attract researchers and venture capital investors. Known for its spicy cuisine and leisurely lifestyle, Chengdu has in recent years attracted the likes of Intel Corp. and IBM, which have set up research and manufacturing bases there. More recently, the flurry of investment activity is in response to Chinese Premier Li Keqiang's call for innovation and entrepreneurship.

China's leaders are seeking new engines of growth as the country's economic expansion hits its slowest pace in 25 years. That's encouraged provinces across the country to create special zones where new ventures can tap funding opportunities and other incentives. While technology startups have been some of the biggest beneficiaries, medical research firms are also getting a boost-giving new life to a Chinese industry that lagged the West for years.

In Chengdu, the local government has set up seven startup-focused funds backed by private capital totaling 700 million yuan to promote industries like telecommunications, health and biotech. The science and technology bureau has a dedicated team to help banks assess start-ups based on the value of their technology and patents. It also has incubators that provide office space and training to new businesses. "There are strong driving forces," in Chengdu, said AllTech founder Zou. "Policies to attract talent and land and tax policies are very favorable."

Like Kang's firm, most of Chengdu's startups are many years away from making big profits off their businesses. That means Chengdu's government also has a long wait before it sees major benefits to the local economy.

Dozens of Chinese cities are launching similar programs, and these new ventures also offer a window into the rising ambitions of Chinese researchers, many of whom have trained overseas. Kang was among the first batch of Chinese to go back to college in 1977 after the Cultural Revolution, eventually earning his PhD at Iowa State University. His primary research focus now is 3D bioprinting, a new frontier of medicine aimed at creating replicas of human organs.

His team has been developing techniques to repair damaged skin, hearts, livers and brains in animals including pigs and monkeys through regeneration-a process that involves creating 3D printed structures that can replicate, for example, a layer of skin or a blood vessels. For organs like a damaged heart, a specialized catheter is used to deliver "bio-ink" or stem cells mixed with nutrients and other growth factors.

Globally, scientists have already succeeded in recreating body parts like bones, but functioning organs are still some way off. In general, 3D printing of tissue is still relatively unsophisticated at this stage and many groups around the world are working on the science, said Anthony Weiss, a biochemistry professor at the University of Sydney.

Although Chengdu has pushed to develop its tech industry for years, "the weight of conventional sectors and high-tech sectors have not changed significantly," said Wei Yuangang, an official with the city's Development and Reform Commission. "But after we implement this new innovation development strategy, we believe the trend will change significantly."

If the city wants to have the same dynamic culture as Silicon Valley, it needs to create vibrant communities where people can easily work, live and find entertainment while avoiding the mistake many other Chinese cities have made in building sterile office blocks around massive streets, said Katrina Lv, an associate partner at consultancy McKinsey & Co.

On a recent Wednesday, on the northwestern outskirts of Chengdu, Bill Li, founder of another startup, demonstrated a small device that can be used to track a baby's diaper and remind parents when a change is needed. Li received 200,000 yuan from the local university and rent-free office space for his 13-member team. Business is taking off, he said-they've sold 6,000 pieces to diaper-makers and consumers.

- China's start-up boom lures talent away from traditional path

- Geely opts to sell interests in micro carmaker

- What they said during Summer Davos Forum

- China decarbonizes for greener growth

- China's economy on alert for multiple shocks

- China's industrial profit growth slows further in May

- PBOC pumps 100 billion yuan into market

- VW to cough up $10.2b in US cheating scandal