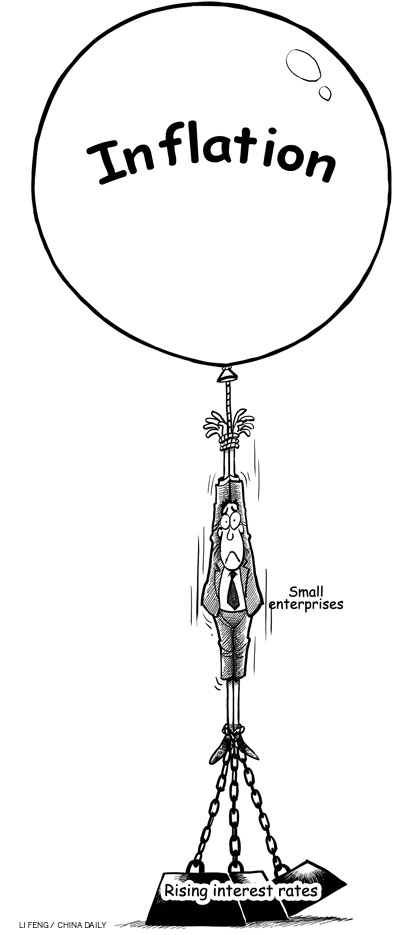

Interest rates stifle small firms

Updated: 2011-07-19 13:57

By Mark Williams (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

China's inflation escalated to the highest level in three years, with the consumer price index (CPI), the main gauge of inflation, jumping 6.4 percent year-on-year in June. Chinese leaders have vowed to give priority to combating inflation. To contain China's stubbornly high inflation, the central bank has raised the benchmark interest rates three times this year, including the latest rate hike of 25 basis points announced on July 6.

However, the bold moves to tame inflation are driving small companies out of business. Companies that were successful and profitable are struggling as their costs of borrowing soar. To help them survive, as strange as it may seem, benchmark interest rates should be raised much higher.

Companies wanting to borrow money in China currently operate in a two-tier system. Those that can borrow from commercial banks are typically large scale and well connected, and include most State-owned enterprises (SOEs). Their cost of borrowing has been low - consistently lower than in India or Brazil - for example, over most of the past decade, even when differences in inflation are taken into account.

But the government rations the amount that banks can lend to keep a lid on monetary growth, so the companies that are left out have to turn elsewhere, to trust companies, informal networks or underground banks.

This second tier of companies faces much higher costs for borrowing. Medium-sized companies can expect to pay annual rates of about 20 percent and small companies can face interest rates double that.

When the government forces banks to limit lending, pushing some companies from the first tier to the second, interest rates for the latter group rise, and it is the smaller companies that come off worst.

Small companies everywhere are more vulnerable to economic shocks. But the difficulty they face borrowing from banks means their position is particularly precarious in China. This has broad implications. Small companies are often the source of innovation, particularly in services. On the whole, smaller companies create more jobs relative to output than larger ones. Accordingly, if China's small companies struggle, so will the government in its efforts to boost the growth of both the service sector and consumption. If China's up-and-coming innovators are starved of funds, the economy's long-run rate of growth is likely to be lower too.

There are other losers in addition to the companies that are beaten in the competition for scarce bank loans. The companies that come out on top are able to borrow cheaply. But this is only possible because banks offer miserly rates of interest to depositors. Chinese families are effectively subsidizing the country's SOEs.

A better system would see loans going to the companies that can invest most profitably, regardless of their size or political connections. The best way to achieve that end would be to ration credit not by quantity but by price, by allowing interest rates to be set by the market. Benchmark interest rates would rise, but the cost of borrowing for many of China's most dynamic companies would fall.

Unfortunately, this is unlikely to happen any time soon. Indeed, benchmark interest rates have probably risen as far as they will in the current cycle.

The liberalization of interest rates is officially a long-term goal, but the government has good reasons for dragging its feet. For one thing, it is not certain that freeing interest rates would lead to significant changes in how loans are allocated today. No bank manager is likely to get into too much trouble for agreeing to a local SOE's request for funds, but China should be moving toward a system in which loan applications are assessed on their financial merits alone. Unfortunately, the banks have been moving the wrong way, with the recent loan-fuelled stimulus response making them appear more than ever like instruments of government policy.

Bank managers have other reasons for preferring to lend to big, well-connected companies, because all things being equal, big companies are less likely to fail. It helps if lenders have the ability to sort the good from the bad. That is true today, but it would be even more important if interest rates were higher.

After all, if one company is willing to pay a higher rate of interest than another for a loan, that might be because it has a profitable investment in mind, but, then again, it could be because the company is in such a bad way that it feels it has nothing to lose from one more roll of the dice. Similarly, charging higher interest rates could tempt otherwise prudent borrowers to take bigger risks in order to earn a return.

Today, the skills needed to identify profitable investment opportunities are in short supply. This is why financial sector liberalization, much disparaged in the rest of the world since the financial crisis, is still essential in China. But progress remains slow, and that probably will not change until the repercussions of the wave of stimulus lending have been worked through. In the short term, a major increase in benchmark lending rates could threaten the viability of any number of ongoing projects.

Simmering concerns that many stimulus borrowers will default, even at current interest rates, also holds back reform. A further reason both lending and deposit rates are still fixed today, with a wide spread between them, is to ensure that banks remain profitable, in anticipation that some of those profits will be needed to clean up a future increase in bad debt.

In these circumstances the slow speed of financial sector reform is understandable.

But the costs are real nonetheless, as the owners of any number of small and innovative but struggling businesses will confirm.

The author is a senior China economist at Capital Economics, a London-based independent macroeconomic research consultancy.