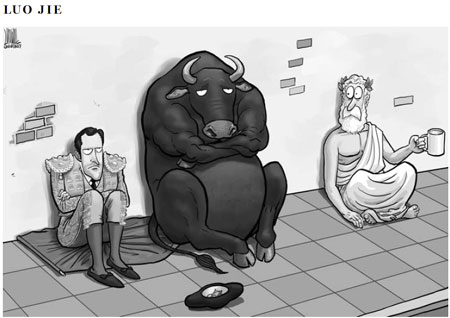

Breathing life into the euro

By Xiao Gang (China Daily) Updated: 2012-06-15 10:58

Eurozone countries should seek ways to avoid breakup and restructure to address the fundamental problems

The eurozone is at a crossroads and the euro is now in an extremely dangerous situation. Until final ways and means of resolving the crisis are found, rather than bailouts which simply buy time, the euro's survival is not guaranteed.

As the eurozone sovereign debt crisis worsens, investors worldwide have begun to flee to safe havens, without thought for the yields on their investments. The US 10-year yields fell to 1.62 percent by the end of May, a level last reached in 1946. German two-year bond yields fell to zero for the first time, and UK interest rates fell to 1.64 percent, the lowest since records for benchmark borrowing costs began in 1703. Financial market sentiment toward the euro shows little optimism.

Even after the European Central Bank pumped more than 1 trillion euros ($1.25 trillion) of cheap three-year loans into hundreds of banks, the continent's banking system remains vulnerable. The growing concern over the possibility of Greece leaving the eurozone has prompted depositors in some countries to withdraw their money from banks - a phenomenon which could bring about disastrous bank collapses.

Ultimately, politics will decide the fate of the euro. Given that the eurozone's problems are not simply economic or technical, it is crucial for the European Union to enhance a greater political union to save the monetary union. However, this is proving very painful and conditions are far from favorable.

The results in recent national elections in the EU show voters unlikely to accept commitment to a stronger political union, and it is hard to see that any useful resolutions and actions to mitigate the crisis being agreed by all 27 nations.

Elections in France, Spain and Greece have revealed deep popular hostility and frustration in the monetary union and the discussed fiscal union. Many voters believe that closer EU integration has left national economies weaker. Germany's industrial output rose in March unlike the rest of the eurozone where industrial production declined. It is estimated that the eurozone economy will contract this year, but Germany's GDP is expected to rise, becoming one of the world's best-performing advanced industrial economies. Unemployment in Germany is near the record lows of 1990, with high business confidence. These continuing divergences make it harder for politicians to reach a consensus on the next steps to solve the crisis.

A series of formal and informal international summits have come and gone without finding fully convincing measures to effectively cope with the crisis. While the G8 summit in May agreed that eurozone turmoil is posing a critical threat to the global economy, and more things must be done to promote growth and job creation and implement fiscal consolidation, there are still a lot of differences on exactly which policies should be implemented.

The ongoing discussions on a number of policies are meaningful. For example establishing a eurozone-wide deposit insurance scheme that can guarantee deposits will be repaid in euro even if the host country leaves the eurozone. Also the issuance of mutual eurozone government bonds aimed at financing for infrastructure and other investments. Rapid change in the European Central Bank's mandate can make it explicit that it enacts its role as the lender of the last resort in pursuit of financial stability.

But in essence, these measures require countries transfer part of their sovereign authority and budget to the European institutions; something that will be very difficult to achieve.

Just as a well-known saying, that is, a country can exist without a central bank, but a central bank would not survive without a country.

However, a Greek exit from the eurozone could tear the bloc apart and trigger unprecedented losses across the world. The contagion could be more severe than the Lehman collapse in 2008.

But at the same time, if Greece is allowed to remain in the eurozone, as most voters hope, without implementing the agreed austerity program, the cost of the total bailout or write-down will be too big to bear.

Therefore, the time has come for the eurozone to consider, though reluctantly, a compromise between avoiding an immediate breakup and restructuring its fundamental problems.

The better path might be to create a new form of euro. For example, the periphery countries could adopt a new joint currency, or a dual currency regime in which the new euro would be used for international transactions and the domestic currency for domestic payments. In this way, it may mitigate the radical impact of a complete exit from the eurozone, as well as increase resilience and flexibility in the monetary union.

Although few have made their contingency plans public, in reality, many governments, companies and banks are preparing for the worst. Multinationals have been sweeping the euro out of their accounts daily to limit their risk in the fear of an overnight devaluation of the currency. Banks are trying to match their assets and liabilities along national lines, seeking to cover loans to a country with funding from the same country. That is one of the reasons why banks shrink their lending to the real economy.

Evidently, the euro is really on the edge of the cliff. What history teaches us is that resolving debt problems is a responsibility of both debtors and creditors. They must be ready to address common challenges and make joint efforts.

The author is chairman of the Board of Directors, Bank of China

- China urges reform of government-linked trade associations

- Chinese yuan extends fall Thursday

- Lenovo sees 51% fall in profit, to slash 5% global jobs

- China mulls licensing non-depository lending business

- China to upgrade cash receiving machines for new bank note

- Pressure remains on Chinese economy as indicators fall short of expectations

- Intl investment fair to focus on Belt and Road

- China to tighten supervision over financing guarantee companies