Economic model must change

(China Daily) Updated: 2012-09-15 14:10Every five years, the National Congress of the Communist Party of China is held to review the past and to plan the future. China's change has been astonishing. The Chinese people today enjoy higher standards of living, greater freedom of all kinds, and a more vibrant, tolerant society. China's economy is now the world's second-largest; it will likely become the largest, doing in decades what elsewhere took centuries.

But dramatic change causes pervasive problems. Can China achieve its goal of becoming a "moderately well-off society" in a world of turbulent markets and limited resources and in a society of social disparities and structural faults?

This challenge is what China's new leaders face.

I'm co-producing with Shanghai Media Group (International Channel of Shanghai) a five-part documentary series, China's Challenges, which, coordinated with the Congress, explores critical grassroots issues. Included are episodes on the economy, society (education, healthcare, housing, retirement), science/innovation, political reform, and beliefs/values. I'm writing and hosting China's Challenges - which will be broadcast on ICS, Dragon TV and CCTV News; and PBS in the US. I'm seeing China's problems close up.

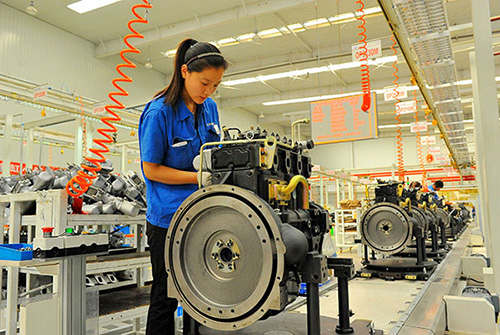

China's economic miracle has been driven by investment and exports, both made possible by millions of migrant workers who personify China's most divisive and intractable problem - the economic and social gap between rich and poor, urban and rural, coastal and inland. But must economic development exacerbate social disparities?

China's growth model - cheap labor, low-cost manufacturing, and energy-intense, high-polluting industry - has come to the end of its historic cycle. China's economy, built of the backs of poor workers, must be transformed. Workers no longer accept low wages, so China's economic model must change or China's economic miracle will end.

How can economic transformation work? Along China's east coast there are many enterprises that began as export engines, enabled by reform and fueled by cheap labor. When the financial crisis crippled overseas markets, many had to close.

The Newcomer Luggage factory in Zhejiang province made low-cost luggage for an international brand. It didn't make much profit and couldn't pay much to workers. But Newcomer changed its business model by creating its own innovative designs and branded products, increasing gross margins from 20-30 percent to 70-80 percent. Salaries of Newcomer workers doubled!

But making innovation work in the marketplace is complex, expensive, uncertain and unpredictable. In short, innovation is risky. Failure rates are very high. So failure must be accepted, or innovation is impossible.

In China, small and medium-sized enterprises, largely private companies, drive the economy, generating about 60 percent of GDP and 50 percent of tax revenues, and providing 80 percent of urban jobs. Nonetheless, policies continue to favor State-owned enterprises, particularly with respect to financing. Less than 15 percent of bank loans go to SMEs.

How can SMEs finance their business cycles? Driven by necessity, an informal system of mutual local financing developed - a private capital chain, not legal, but not quite illegal either. The government didn't much like the gray-market financing scheme, but didn't stop it.

Henglong Small-loan Company in Wenzhou, the center of entrepreneurship in China, lends to small and micro agricultural enterprises - in total, more than 4 billion yuan ($630 million, 480 million euros). Henglong can set market-driven interest rates up to three times higher than what banks offer. (But to SMEs, "what banks offer" doesn't mean much because banks won't lend much.)

In 2012, China's State Council set up a pilot financial zone in Wenzhou, legalizing small loan companies.

If financial reform in Wenzhou affects private business, financial reform in Shanghai affects China's entire economy. Can Shanghai become a world financial center? I ask Fang Xinghai, director of the Shanghai Finance Office. "Shanghai serves a continental-sized economy, and we want to be New York and London," he says. "Let's imagine China's economy reaching the size of the US economy, the yuan becoming a fully convertible currency, and China's domestic financial market becoming fully open, then Shanghai can be at the same level as New York."

- Vice-Premier Wang urges capital market reform

- China's reform, opening-up contributes to world economy

- China's economic growth slowly stabilizing

- Let reform and opening-up be the guide

- On right track for growth model change

- China can avoid hard landing: Singapore deputy PM

- Innovation transformation

- Growth model shift should go 'full speed ahead'

- More pro-growth policies expected for China's economy

- RRR cut boosts property stocks

- Wenzhou whizzes take it easy in realty market

- China Life to buy 23.7% stake in China Guangfa Bank

- Beijing Utour acquires Huayuan MNB for 2.6b yuan

- Companies can profit from serving foreigners as expat arrivals rise

- Individual taxpayers can expect only minor changes from reform

- Yidao eyes IPO to take on Didi Kuaidi, Uber