Global value chains in the world economy

By Pascal Lamy (China Daily) Updated: 2012-09-19 08:09

Global value or supply chains are not new. For decades companies have been importing parts and components for the finished goods they manufacture. Technology has reduced the cost of distance spurring multilocalization. What is new is how pervasive they have become and the degree of complexity they have attained.

What is also new is the public debate about what these intricate systems mean for the world economy, for individual economies and for development. This debate takes place against a backdrop of constantly shifting circumstances and evolving technology which raise challenges for policymakers who must ensure that any conclusions drawn or actions contemplated are in line with the realities on the ground.

This means viewing trade from a different perspective. Measuring trade in gross value terms no longer makes sense in a world where trade in intermediate goods - a reasonable proxy for global value chain activity - constitutes more than half of world merchandise trade. Trade flows must be measured today in terms of the value added by each production link along a supply chain to the final value of goods and services.

When viewed through the value-added prism trade balances are not what they appear to be when measured as gross flows. Subtracting imported inputs of goods and services from the total value of production provides a truer picture of the national contribution. This measure of trade also gives a more accurate picture of true bilateral trade balances.

Measuring trade in value-added also offers a much clearer understanding of the size and nature of each national contribution to a final product. Under current arrangements, exports of iPads from China to the United States, for instance, contain a small fraction of Chinese value-added and little Chinese technology. Yet from a gross trade flow perspective, an iPad imported from China into the United States looks like an expensive high-technology product made in China, when in truth it is "made in the world", with components from many Asian economies.

Thirdly, value-added statistics are important because they tell the true story of the interdependence that has been forged over the years among countries through trade. We live less and less in a world of "them" and "us" when it comes to the international economy. Countries are increasingly fused together by joint production arrangements manifested in global value chains.

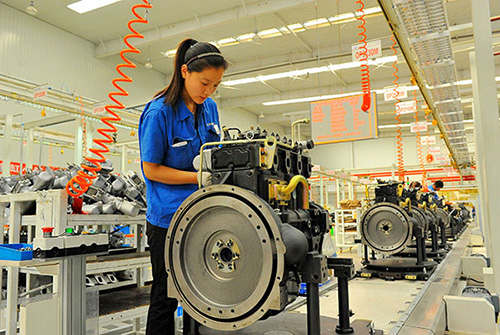

What do global value chains portend for individual economies? Governments are interested in securing a profitable place on global supply chains and deriving as much as possible of total value-added. As consumption levels increase in China, supply chains will more frequently end within its borders. That means that branding, marketing and retail margins - often a significant part of value added and job creation along a chain - will be done in China.

Similarly, as its economy diversifies, China will become a growing source of physical components and services used in the production process. These inputs may be supplied locally or they may be exported to foreign locations along the value chains. This process is likely to more than offset any relocation of assembly operations moving away from China as production may be less expensive elsewhere.

Involvement in global value chains allows incremental specialization through the production and trading of tasks and components rather than entire products. This is the contribution that participation in global value chains brings to a nation's growth, economic diversification and development. If countries are to participate effectively in global value chains and in the progressive upgrading of this participation governments must provide an appropriate policy environment.

Non-tariff measures, whether purely administrative in nature or designed to meet public policy objectives, can be applied in such a way as to frustrate trade, rendering vital imports of parts and services scarce and costly. Hidden protectionism through these measures can occur both in the design and the application of measures and will frustrate the effective operation of supply chains. When components and services cross national frontiers several times the cost impact of such policies multiplies.

Such measures can however be designed in ways that are less restrictive of trade. This applies not only to trade policy but to investment policy and intellectual property protection regimes as well. Of course other factors are vital too, such as physical and human capital, the macroeconomic environment and policy stability.

Staying ahead of the curve in this complex environment is a major challenge for producers, customers and policymakers. But for those who wish to be competitive in the marketplace of the 21st century, there is no alternative.

The author is director-general of the World Trade Organization.

(China Daily 09/19/2012 page8)

- China's deficit increase boon for growth, reform: official

- China sets deadline for VAT reform

- Ministries give hope to ride-sharing services

- China to well handle bad loans: finance minister

- NDRC Minister: China can absorb laid-off labor

- Finance Minister takes questions from the press

- Steamed bun brand expands to US

- BMW quickens pace of localization strategy in China