Tapping the potential of Africa's oil

By Zheng Yangpeng (China Daily) Updated: 2012-09-26 10:20Chinese oil companies such as CNPC are making the most of their technology, hard work and respect for local people to tap African oil reserves, as Zheng Yangpeng reports from Niger and Chad

After a two-and-a-half-hour flight from Niamey, the capital of Niger, the small plane landed at a small airport. The airport, Jaouro, is dubbed jiaorou (which means "tender" in Chinese) among Chinese workers here.

But conditions here are just the opposite of what its Chinese name implies. Lying in the heartland of the southern Sahara, the world's largest and roughest desert, the lonely base here is routinely subjected to scorching heat, sandstorms, scorpions, snakes, malaria and even robberies.

|

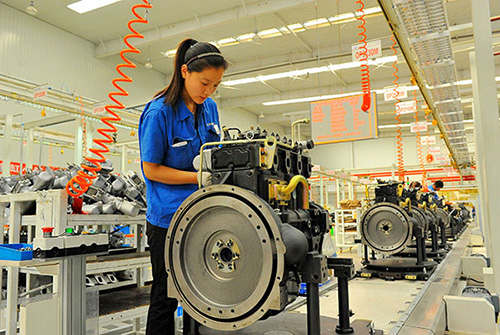

Niger's president Mahamadou Issoufou plugged his car with oil that was produced in his own country. [Photo/China Daily] |

None of this put off China National Petroleum Corporation, China's largest oil producer, which was determined to extract Niger's first barrel of oil from the desert.

For the past half-century, people in Niger, a former colony of France, were told there were oil reserves beneath the Sahara. Oil giants came and went, as they either failed to find oil or what they found was too little to justify commercial exploitation.

Then came the Chinese oil company, which is the fifth operator of Niger's Agadem block.

In June 2008, CNPC signed a production sharing agreement in Agadem with the Nigerien government, promising not only to build the oilfield, but also a pipeline and a refinery.

"Typically, oil giants are reluctant to build refineries as the profit is much lower than producing crude, let alone if highly productive reserves have not been found," said Fu Jilin, general manager of CNPC International in Niger.

The groundwork took place at a furious speed. A prospecting team set foot in Agadem less than a week after the agreement was signed.

Various engineering contracts were soon concluded. Jaouro airport, a critical project that would shorten the journey time between Niamey and Agadem from three days by car to less than three hours, was finished in 66 days. The speed was remarkable, given that all the earth the construction project needed had to be transported from outside the desert area.

"The sands of the Sahara are too fine to be used for construction purposes," said Fu.

The construction spree ended abruptly on Feb 18, 2010, one day before the then government was to grant the exploitation license to CNPC. On that day, the then government was replaced by a military commission. Suddenly, Fu found his company was confronted with mounting uncertainties.

In August 2010, the transitional government granted CNPC its long-awaited exploitation license. An agreement on the retail price of the refined oil was not settled until September 2011, after marathon negotiations with the elected government, led by President Mahamadou Issoufou.

"The Nigerien side had doubts about our price, and insisted that it was too high. But if we had agreed to the price they wanted, the refinery would certainly run at a huge loss," Fu said. "With a calculator in hand, I calculated the composition of the price in front of them, over and over again," he said.

"Please understand Niger's culture of suspicion. Nigeriens normally don't trust things done by others. It is not targeted specifically at CNPC," said Djibo Salamatou, former energy and petroleum minister, who had participated in the negotiations.

Nov 28, 2011 was a historic day for Niger. CNPC's refinery produced the first barrel of refined oil. Nigerien President Issoufou filled his car with fuel that was produced in his own country. It was an emotional moment for him, for the Nigerien people and CNPC employees.

"Fifty years ago, Niger embarked on the path of oil exploitation. Not until today did it produce the first barrel of oil. Niger has ushered in a new period of development," Issoufou said at the event.

The Agadem oilfield, from which the oil is transported through a 462.5 kilometer pipeline to the refinery in Zinder, now has an annual production capacity of 1 million tons.

Chinese spirit

The morning breeze of the Sahara brushed over houses, a basketball court and green plants that surround Jaouro airport. Standing there, it was difficult to imagine how tough the situation was four years ago when the base was first built, with no available equipment and no logistical support.

- Oil firms plan for Mideast turmoil

- Technical breakthrough in oil exploitation

- CNPC overseas equity oil output up 4.6% in H1

- PetroChina pipeline turns on gas supply

- Africa stands to gain from China's economic transition

- Entrepreneurs urged to boost Sino-African ties

- Nigerian envoy urges China to 'cut import tariffs'

- Niger eyes China's help in agricultural production

- Policies aimed at luring success back home

- HK martial arts movie in spotlight over box office fraud

- Turning passion for reading into profit

- Battery maker Tianneng plans base in Southeast Asia

- Action needed to address a burning issue due to smogs

- Launch of strategic emerging industries board in doubt

- Eslite bookstore story reads like a page-turner

- Auckland hails Fu Wah for building signature hotel