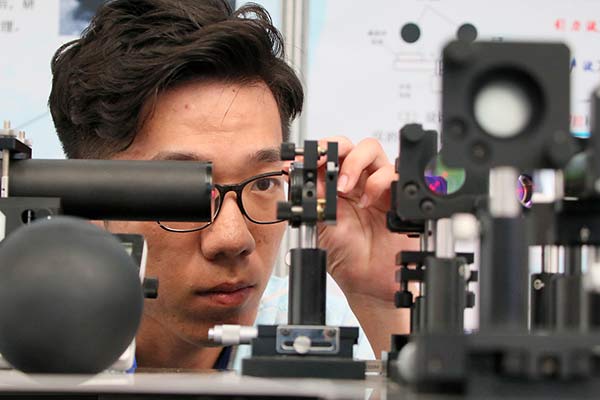

Job dilemma

|

|

|

Job seekers look around at a job fair at Nanchang University in Jiangxi province on May 23. |

Almost 7 million—this will be the number of college graduates in China in 2013, a year which promises to be the toughest job hunting season in Chinese history.

Never before has the nation had so many graduates competing for jobs, particularly when so few are available. The number of vacant positions offered by employers has shrunk by 15 percent. Without a doubt, the job market is white-hot.

As of April 19, less than 30 percent of graduating seniors in Beijing had signed contracts with employers. Shanghai faces a similar situation.

The title of "college student," once a shining halo for Chinese people in the 1980s and 1990s, is now virtually synonymous with "soon-to-be unemployed."

Harsh reality

"In the late 1990s, the number of college graduates just exceeded 1 million. Now we have almost 7 million," said Xiong Bingqi, vice president of the Beijing-based 21st Century Education Research Center.

The reason for such an increase lies in the expansion of college enrollment in the late 1990s as the government hoped to make more people have access to higher education. The expansion was also expected to boost consumer spending to fend off the impacts of the Asian Financial Crisis, as well as to ease immediate pressure on the labor market.

Expanded enrollment finally gave 70 to 80 percent of high school graduates the chance to enter college. Figures from the Ministry of Education show that the number of college graduates already exceeded 6 million in 2009 and since then the number has grown steadily.

The bleak employment situation for college students has been a problem for years and is just becoming more prominent in 2013.

"While at the same time, the majors in colleges haven't changed that much as many colleges are not market-oriented and set up majors en masse," said Xiong.

In first-tier cities including Shanghai, Beijing, as well as Guangzhou and Shenzhen in Guangdong province, where most graduates wish to make a living, young job hunters cluster in low-rent tenements in old parts of town or on the outskirts.

In 2009, Lian Si, a scholar at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing and then a post-doctoral fellow in Peking University, coined the term "ant tribe" based on three years of research of recent graduates.

"Now the living cost in such cities is even higher and with the displacement of such areas, it is much more difficult for the college graduates to find cheap accommodations," said Zhang Yi, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

For 25-year-old Fan Lihui, who just got his master in business administration, the situation is worse than previously imagined. "I lowered my salary expectation to 2,500 yuan ($407) a month, but I still couldn't get an interview," Fan told national broadcaster China Central Television.

In comparison, criteria drafted by netizens in early 2012 state that to be a white-collar worker in China, one needs to earn a monthly salary of no less than 20,000 yuan ($3,258), own an apartment with at least two bedrooms and a car worth around 150,000 yuan ($24,435).

The criteria, though lacking systematic social research and statistical analysis, to some extent, reflect China's public opinions on the financial requirements of leading a leisurely life amid soaring prices in everything from real estate to food. It also suggests that employability itself is closely tied to perceptions of socioeconomic status, said a report by Xinhua News Agency.

Yan Zhaolong, in charge of Nanjing Andemen Job Fair for Migrant Workers, is inundated with college students consulting him for opportunities as migrants. The job fair ended setting up a window specifically for graduates.

"I feel sad about this," said Yan, who is over 40 years old. "In my days, college students were people that we should admire. I never thought they could end up like this."