Ideal drivers of progress

By ED Zhang (China Daily) Updated: 2015-03-23 08:00

What people saw from the National People's Congress annual session in Beijing in the first couple of weeks of March was clearly a picture of transition, as a perfect reflection of China's transitional economy.

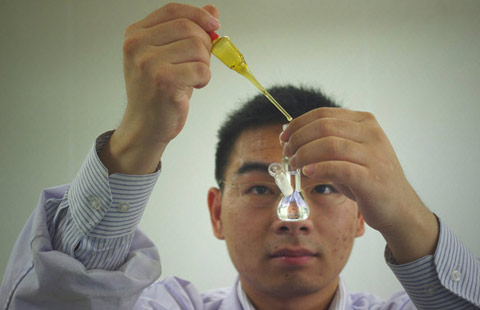

If transition is defined as a process that starts from the past and drives through the present to reach the future, then one could discern all of that from what recently transpired at the Great Hall of the People. When Premier Li Keqiang was talking about "mass innovation" - or a society flourishing with thousands, if not millions, of small companies driven by digitally powered leading technologies - he represented a country that is not today's China, but the vision of his colleagues at the top level.

In sharp contrast, officials from some provinces that are behind the rest of the country in economic growth (and in public services) continued to raise their hackneyed appeal - heard by China observers in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s - for bailout money from the central government for their mining companies (which are apparently running out of resources), for their workers stuck in low-paid jobs, and for their cities that are saddled with dilapidated public services. They are, as it were, the shadow of a China that is fading from public memory.

In fact, from many of the places featuring poor government reform and weak market vitality, like the old industrial cities of the 1950s in the rust belt of Northeast China, there has been a continuous drain of population. Young people don't want to wait for the government handout and they have been attracted by the opportunities and services in coastal cities.

Of course, one may look at this or that chart to determine the country's state of health. Recently there have been many of them, floating about in general investment reviews, but they just carry the average numbers. None of them tell where change, if it ever happens, is coming from.

This is a country of great diversity, and a country whose annual economic growth, in absolute numbers, would be close to a country like Sweden. When times are good, its cities can't all be exciting in the same way, and they can't be all boring to the same degree when times are bad. There must be people who are trying to do something different somewhere.

In reality, there are about two dozen or so cities that host most of the country's realistic activities and, perhaps, opportunities. They are also where the country's most highly educated people gather and build their companies. To a great extent, how China's transition evolves and succeeds depends on these cities continuing to flourish. Chinese officials tend to present them in four or five so-called city clusters. But the city clusters just belong to a government plan. Not much action has been taken so far to make them real.

The key is, however, to look at what people are doing in those few cities to decide how the country's transition progresses.

They will be the cities that:

Have a longer history of reform and opening to the global market, and with a high mixture of local and international enterprises.

Have a smart and business-friendly local government that is not plagued by corruption scandals, mass protests and wasteful public projects. It must particularly have a lower ratio of local government debt to GDP.

Have a large migrant labor force, joined by workers from impoverished rural areas and engineers and managers trained from abroad.

Have a large base of competition and collaboration and many privately owned small companies.

Have a good base of education, represented by a multitude of technical schools suitable to the current stage of development and able to meet the demand from newly emerging industries and services.

Have a relatively good state of public infrastructure but not so much of an imbalance in the housing market, which must have relatively low residential housing prices, a good supply of not-so expensive office space. The city must also have a relatively good environment (hopefully with less smog than Beijing).

Most of these types of cities are near China's coast. Others are large regional business hubs in the nation's interior. If these cities can grow stronger in both their economy and government services in one to two years, they can be leaders of real progress. But if they fail, that would be a totally different story.

The author is editor-at-large of China Daily.

- Israel requests to join Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

- Chinese stocks rebound on April 1

- China, the West in Africa: more room for cooperation than competition

- Nanjing cuts taxi franchise fees

- Air China increases flights to Milan, Paris

- JD.com raises delivery charges

- Veteran corporate strategist upbeat about China economy

- L'Oreal China sales revenue up 7.7% in 2014