Reducing social security burden not an easy job

By Zheng Yangpeng (China Daily) Updated: 2016-03-31 07:43

|

|

An elder shows her social security card in Nantong city, Jiangsu province, March 30, 2016. [Photo/IC] |

State Council approves regulation allowing national fund to manage local surpluses

In response to the central government's call to reduce the burden on businesses, 12 provinces and municipalities have cut social security payment requirements for employers and employees.

But analysts said the pension fund, the largest of all government programs, is unlikely to see cuts in payouts.

China Daily's compilation of information shows that the reductions mostly concentrate on smaller programs dealing with such things as workplace injuries, unemployment and childbirth insurance.

For example, in Tianjin, employers had to disburse 2 percent of an employee's monthly payroll to the unemployment insurance fund and 0.8 percent to the childbirth insurance fund. Now the ratios have been cut to 1 percent and 0.5 percent.

In a related move, the State Council, China's Cabinet, approved a regulation on Monday that applies to the National Social Security Fund. It allows the fund to take over management of local governments' social security surpluses.

Established in 2000, the NSSF supplements the numerous social security funds run by local governments. Unlike those funds, which mostly rely on payments from employees and employers, the 1.51-trillion-yuan ($233 billion) NSSF is mostly funded by fiscal revenues. Run by a professional council of investment experts, it earned 15.14 percent in returns in 2015.

Currently, only Guangdong and Shandong have entrusted their surpluses to the NSSF. Under the new regulation, more are expected to follow suit.

The cuts in social security contribution requirements by the 12 provinces and municipalities-while welcomed by companies and individuals-represent only a small fraction of the total pie. Employers' combined payments for unemployment, work injuries and childbirth insurance accounted for just 3.3 percent of payroll, while 20 percent of payroll goes to the pension fund and 8 percent for medical insurance. Without a drop in those two categories, the payment burden is only slightly reduced.

Of the places adopting the cuts, only Shanghai reduced its pension fund requirement (from 21 to 20 percent), which basically returned the city to the national norm. Xiamen in Fujian province, cut its medical insurance ratio to 7 percent.

Nationwide, employers and employees still pay about 39 percent of payroll to the five social insurance programs-among the highest in the world, despite a decrease from 39.6 percent.

Deeper cuts to the pension fund and medical insurance ratio are needed, experts say, but simply cutting the nominal ratio might miss the bigger picture.

Dong Keyong, a social security expert at Renmin University of China, said in most Chinese companies, particularly in the private sector, actual payments are lower than the 39.6 percent ratio often reported because the definition of "payroll" is not the same everywhere.

"Every local government sets a theoretical base for calculation-which is lower than an employee's actual salary in most cases. So, the actual payment is much lower," Dong said. "It is misleading to focus on the payroll ratio."

The right approach, Dong said, is to overhaul the pension system so employees not only rely on the basic pension fund scheme mandated by the State but on commercial pillars.

"Under the current system, it is unlikely that the pension fund payment ratio can be lowered" from the current 20 percent, Dong said, citing several localities that are struggling with deficits in their pension fund accounts.

- Denmark ready for China's new growth model: ambassador

- Chinese shares close slightly higher - March 31

- Gree agrees to pay $15m penalty to US safety authority

- Bank of China plans to officially open Prague branch in April

- McDonald's looks for strategic partners as it eyes bigger bite

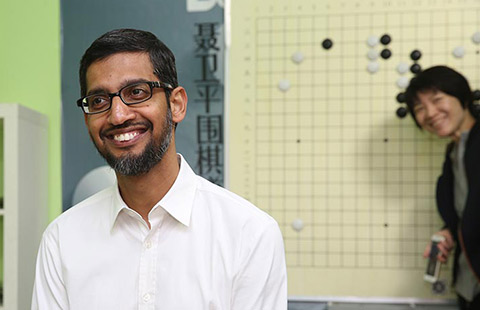

- Google CEO Sundar Pichai visits China's Go school

- Wanda mulls taking property unit in HK private

- Central bank pumps more money into market