ADB focusing as know-how provider

(China Daily) Updated: 2016-06-03 08:08

|

|

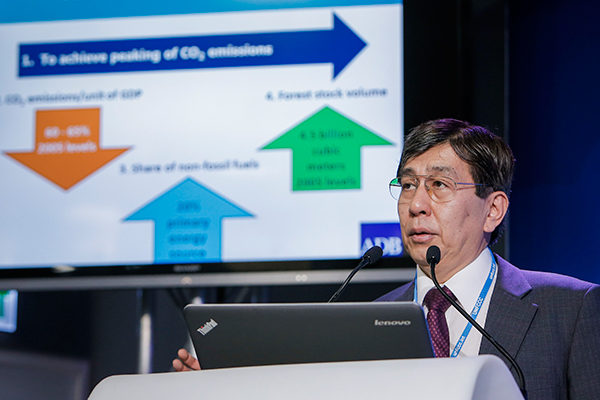

Ayumi Konishi, director-general of ADB's East Asia department. [Photo/Xinhua] |

Bank points to successful partnership with Hebei in reforming its energy policies

How can an international organization with limited resources stay relevant in a vast country awash with money, such as China? Asian Development Bank's experience might offer an answer to that question.

The Manila-based multilateral development bank, under President Takehiko Nakao's leadership, has crafted a strategy named "finance++": the first "plus" standing for "knowledge" and the second for "leverage".

In China, its strategy has been further revised to "knowledge++", according to Ayumi Konishi, director-general of ADB's East Asia department.

"For us working in China, we say knowledge++. Money really doesn't come first. Our main business in China is knowledge," he told China Daily in an exclusive interview.

The bank's strategy was formed in the context of ADB's lending to China, which with around $1.7 billion approved in 2015, equates to less than 0.2% of the $1 trillion of total loans at China Development Bank, a domestic policy bank. To remain relevant, said Konishi, it has to offer more than just capital.

To get a sense of what "knowledge" means, the ADB executive said take a look at the greater Beijing clean air program, for which the bank in late 2015 granted a $300 million policy-based loan. Together with another 150 million euros ($168 million) from an European agency, the funds only accounted for 10% of the total investment. But, Konishi said, ADB managed to play a key role in providing technical know-how.

With ADB's support, Hebei province, which contributes most of the pollutants in the region, is making fundamental reforms of its energy policies, switching from coal to cleaner energy, promoting public transport in urban areas, and increasing the use of biomass for energy in rural areas.

ADB also helped develop a monitoring and analysis system and helped strengthen environmental regulatory enforcement.

In addition, employee retraining and social protection will be provided for workers affected by the industrial transformation.

Konishi said some of the actions are follow-through efforts initiated by Hebei earlier, but the problem was that many targets were left unimplemented.

For example, 11 cities in Heibei set themselves emission control targets, but some didn't even have the necessary monitoring stations.

Besides designing new policies, much of ADB's work has been working with Hebei to oversee their actual implementation, review the policy, and discuss the next steps, Konishi said.

"I don't know how many times our staff come to China to discuss with different government departments the policy details," he said. He added he had himself flown to China twice in a month, spending most of the time in discussions with heads of different departments.

Konishi acknowledged that working through the myriads of Chinese departments was "not easy". However with ADB's presence, officials from different departments were able to "pool together" to meet his bank's team, facilitating a coordination that could otherwise be difficult to achieve.

Konishi said ADB's expertise is reflected in various facets of one program. Although having a simple theme, the greater Beijing clear air program actually involved many different aspects, ranging from energy policies, public transport, urban development, institutional strength and even social policies, he said.

From project design to implementation to review, ADB not only mobilized its China office staff but a major workforce in Manila. At least half of ADB's knowledge department staff have been involved in projects in China, Konishi said.

- AIIB to co-finance projects with World Bank and ADB

- China's growth target achievable, risks manageable: ADB economist

- Nepal should attract investment from China to achieve economic growth: ADB

- ADB to fund $250m to support China's treatment of industrial wastewater

- ADB raises annual lending to China to $2 billion mark

- State Grid ready for ultra-high-voltage tech exports

- Singapore's Temasek, GIC buy $1b stake in Alibaba

- Pushing for change with passion

- COFCO on the hunt for M&As

- Go against the grain to reap investment dividends

- CNPC to prioritize natural gas over next five years

- In China, Wal-Mart meets its match: Sun Art Retail

- Lenovo shares hit hard on Google exit