Ancient irrigation system stands test of time - and quake

(Agencies)

Updated: 2008-05-23 15:23

Updated: 2008-05-23 15:23

Dujiangyan - High above the world's oldest operating irrigation system, Zhang Shuanggun, a local villager, stands on an observation platform cracked by China's massive earthquake last week.

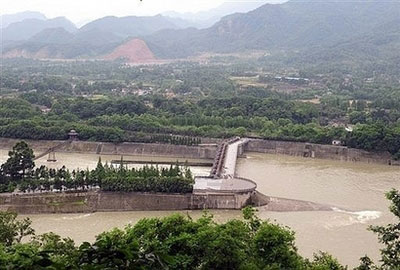

An overview of Dujiangyan's ancient irrrigation system on May 21, 2008 in southwest China's quake-stricken Sichuan province. Despite its close proximity to the quake, the irrigation system suffered only minor damage and was not compromised, according to the government. [Agencies] |

She has a simple answer for why the ancient, bamboo-based Dujiangyan irrigation system sustained only minor damage, while nearby modern dams and their vast amounts of concrete are now under 24-hour watch for signs of collapse.

"This ancient project is perfection," Zhang said.

From the hillside platform, the workings of the ingenious irrigation project that is now a UNESCO World Heritage-listed site are clearly visible.

Built from 256 BC, the system involved diverting the Minjiang River's flow using man-made islands built on bamboo frames that allowed water and fish to flow freely underneath.

UNESCO, the United Nations cultural organisation, says the system "controls the waters of the Minjiang River and distributes it to the fertile farmland" of the plains.

It is "a major landmark in the development of water management and technology and is still discharging its functions perfectly."

The irrigation system is at the foot of mountains on the edge of Dujiangyan, about 50 kilometres (32 miles) from the epicentre of the May 12 quake which measured 8.0 on the Richter scale and killed more than 40,000 people.

Yet despite its close proximity to the quake, the system suffered only minor damage and was not compromised, according to the government.

At the same time, several dams were damaged by the earthquake and are now under constant watch for signs of collapse amid concerns they may not be able to withstand strong aftershocks or flooding.

"The earthquake this time has caused damage at various levels to reservoirs and dams," Gu Junyaun, the chief engineer at the State Electricity Regulatory Commission said this week.

"Dam safety experts have been put in place to monitor the operation of the dams 24 hours a day."

Thousands of people have been evacuated in various areas of quake-hit Sichuan province due to fears of bursting dams.

Qushan, a major town that suffered major damage in the quake, is being relocated altogether partly because of the threat that a dam above it will collapse and send torrents of water through the area.

The contrasting fates of the ancient irrigation system and the modern dams offer a cautionary tale for China as it continues its love affair with trying to tame its vast rivers.

Hundreds of dams have been built, or are being constructed, across the country, and environmentalists have repeatedly warned of the folly of doing so in quake-prone areas such as Sichuan.

But no one has such fears about the Dujiangyan irrigation project.

"The irrigation system is reliable and solid," said He Quyun, 66, a woman who lives above the project in hills which are prone to rock falls since the quake.

"The skills of the ancient people, the architect, were so high," said another area resident, a former village Communist Party secretary who declined to give his name.

He was resting outside the now-closed ornamental gate through which tourists would normally visit the irrigation project.

From above, the project looks deceptively simple.

The river splits around a heavily forested and slightly curved island about one kilometre (0.62 miles) long.

At the top of the island, a protrusion which residents call the "fish mouth" pokes into the river and helps it divide. On one side is a modern dam with flood gates through which the river passes.

On the other is a narrower channel which flows towards the plain where it waters the fields of Xu Shifu and other farmers.

"Yes, it comes from there," Xu, 52, said, leaning on a hoe beside his brown fields of wheat almost ready for harvest. "It's a small tributary... it's originally from the fish mouth."

While his wife planted corn seedlings along the edge of the wheat field, Xu explained that if his paddy needs extra water, it could be directed into his fields through a system linked to the ancient water works.

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|