Hot on the Web

Donors kept in the dark on where money goes

By Zhang Yuchen (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-05-27 07:47

|

Large Medium Small |

|

A group of children at Sun Village, a charity to help the children of convicts in Beijing, relax after getting a share of the food donated to the charity. [China Daily] |

Is a lack of transparency driving a wedge between charities and donors, and undermining the charitable spirit? Zhang Yuchen in Beijing reports.

Do you know where your money goes when you donate to charity?

Studies show that many people who support worthy causes in China admit they have absolutely no idea how or where the money is being spent.

As the country has no law requiring aid groups to publish monthly or even annual accounts, experts say the vast majority of donors are in the dark about where funds go due to basic lack of transparency in the sector.

"Charitable organizations seldom respond to donors' requests for information about financial reports so few donors have a clear understanding of what their money is used for and what effects it brings about," said Deng Guosheng, an associate professor at Tsinghua University's school of public policy and management.

The situation has resulted in serious problems when it comes to supervising grassroots charities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and threatens to undermine the growing charitable spirit among the Chinese, he said.

Following the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province, the nation raised record amounts of money to help survivors. Those records have since been broken following the disaster in Qinghai province in April. So amazing was the response that media analysts suggest the disaster triggered an explosion in compassion, which has continued to spread throughout the country.

The amounts being donated have also steadily increased year on year over the last decade, official figures show.

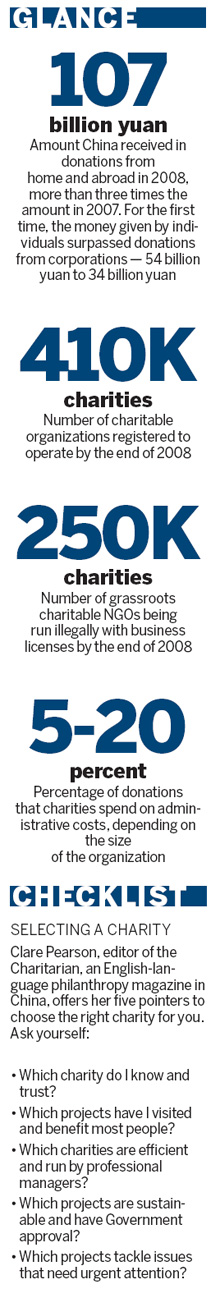

China received 107 billion yuan in donations from home and abroad in 2008, more than three times the amount in 2007, according to the Blue Book on Charity Donation Development in China (2003-07), an independent report sponsored by China Philanthropy Times. For the first time, the money given by individuals on the mainland surpassed donations from corporations - 54 billion yuan ($7.9 billion) given by individuals, compared to 34 billion yuan by corporations.

However, in a recent survey of people who donated to the Sichuan relief efforts, Deng found that less than 5 percent of the 1,684 who responded know exactly how the money is being spent, while more than 60 percent had little or no idea. (Authorities have published financial accounts during the ongoing reconstruction of Sichuan.)

The trend is also typical among people who give regularly to many Chinese charities, said the professor, who added that although the public is growing more aware of how they work, the overall disclosure of information is far from sufficient.

Trust is fundamental to how most charities are run in other nations but "getting all charities in China to be 100-percent transparent has proved virtually impossible", said Deng, who also works in the university's NGO Research Center.

About 410,000 charitable organizations were registered to operate by the end of 2008, while another 760,000 were running but still waiting for official documentation, said a report in the Blue Book of Philanthropy 2009, an independent academic evaluation of China's charity sector.

Very few publish any kind of annual progress or spending reports, and donors rarely think to ask for them, say analysts.

"A lack of professional management, transparency and trust are major problems facing the charity sector in China," said Yang Tuan, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' institute of sociology, who co-authored the Blue Book of Philanthropy 2009. "The fact that there is no charity association is the biggest problem, though. There is simply no co-operation that allows these groups to confront and overcome common obstacles, as well as provide mutual supervision."

Fund-raising problems

China's first and, as yet, only regulations for charitable NGOs were implemented in 2004 and apply just to the administration of foundations. A draft of the new Charity Law, which is expected to contain stricter legislation over fund management, was submitted to the State Council last year.

|

|

Under the current rules, NGOs have to be affiliated with a government department before they can register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Finding one is no easy task, however, and there are some 250,000 grassroots groups that are instead being run illegally with business licenses, the Blue Book of Philanthropy 2009 says.

"Also, only foundations that are affiliated with a government department or have ties with an authority enjoy the luxury of being allowed to raise money in public," said Deng. "Grassroots organizations always suffer a chronic shortage in donations."

Of the 943 foundations registered in China that can legally raise funds in public, 83 are government-owned NGOs (otherwise known as GONGOs), said the professor.

Collecting money from the public without the proper authority is illegal and can lead to serious consequences for charity organizers, and the groups will automatically be shut down.

"This is a concern for many of my friends who work for grassroots NGOs," said Guang Pu, the 30-year-old director of One Heart, a legally registered non-profit orphanage in Xiamen, Fujian province, that publishes monthly financial reports for donors. "The rules effectively stop a lot of grassroots charities from raising awareness of their cause and soliciting public donations."

|

The lack of clear governance has led to conflicts between charity organizers and donors.

Sun Village, one of China's first charities for children of convicts in Beijing, has been well supported for many years, including by several multinational companies.

However, complaints in recent years by donors over its opaque spending habits have cast doubts over its reputation.

The village director, Zhang Shuqin, denied the claims and feels she was unfairly criticized in press. She blamed the charity's difficulties on the fact that it lost its affiliation with the government in 2003.

When Sun Village lost its link to the local authority, "I begged more than 10 other departments to help us", said Zhang, who launched Beijing Sun Village Children Education Consultancy in 2003. As none agreed, she opted to register the organization as a business with the capital's administration for industry and commerce - make it illegal for the village to raise funds publicly.

"My company got involved (with Sun Village) years ago but we've started to feel more and more uncomfortable (about its management) in recent years," said a Beijing-based communications director for a multinational corporation who did not want to be identified. "We've usually helped by donating food for the children but recently we've continually received calls asking the cash donations, without any explanation of how the money will be used."

However, the school's director argues that her critics do not understand how hard it is to run a charity in China.

"Why do (the people criticizing me) not recognize the hardship I've been through?" said Zhang, a fast-talking woman who has also been accused of being too aggressive. "I don't think they have any right to say anything about me or Sun Village.

"We cannot get (affiliated), so why do (donors) think I should publicize our financial records?" she added, before offering to show China Daily the charity's accounts. "The privacy of the convicts' children is the only reason why I am reluctant to make my financial report transparent to the public. Issues related to people in jail is very sensitive in China and I don't want the children to be hurt to any extent."

Most charities do not offer detailed information about donations and spending unless donors specifically ask to see some, say analysts. The Beijing communications director admitted her company had never formally requested any financial reports from Sun Village.

Regularly publishing accounts can actually be a heavy financial burden for charity minnows.

Dandelion School, a charitable education project targeting the children of migrant workers in Beijing, is consistently praised for its transparency. Yet due to the extra cost of distributing its accounts, the group can only keep donors updated on the specific projects they contribute to.

"That costs less than posting the whole package, such as how the money was spent and what kind of effects it has had," said Clare Pearson, chief editor of Charitarian, the only English-language philanthropy magazine published in China.

The accounting can also be complicated by the fact charitable NGOs also rely on donations to cover running costs. This can be difficult to break down for people not working in the charity sector, explained Deng.

"The public in China isn't really familiar with how NGOs are managed and often don't recognize that the costs of running a charity - people's wages, transport, etc - often comes from donations," said the professor. He estimated that, depending on the size of the charity, about 5 to 20 percent of the money raised goes towards administrative costs.

However, grassroots NGOs often do not allocate enough funds towards its management, which can also contribute to the slow disclosure of information to donors, said Li Dajun, program manager for the China Social Research Center affiliated with Peking University.

"They are so busy looking for fund-raising opportunities (to support their cause) that they leave little room for their own development as a charity," said Li, who worked with several NGOs between 2003 and 2007.

"Ultimately, if trust is built (between a charity and its donors), few will doubt how the money is spent," added Pearson, who is also a corporate social responsibility manager for the international law firm DLA Piper.

Selection process

Carefully selecting a charity that is run by professionals is key to ensuring any donation will be spent correctly and efficiently.

|

Traders buy donated clothes from Sun Village, which they will resell them at a Beijing market. [China Daily] |

"Sometimes, when people decide to find a charity to support, their eyes are always caught by the famous or popular ones, although neither of these qualities guarantee professionalism or qualifications," said Deng at Tsinghua University.

As the charity sector continues to develop, so too does the experience of those working in it. However, the current demand for human resources at NGOs far outweighs supply.

"The first generation of China's NGO founders knows less about managing charities, so they have stuck to the tradition of being family run and giving relatives jobs in the organization, which creates more suspicion," said a publicity expert who has studied the development of NGOs in China for more than a decade ago but did not want to be identified.

Sun Village is one of those organizations that have been accused of being "family run" and media reports claimed Zhang employs two daughters and a son-in-law to manage the school.

However, the under-fire director fiercely rejected the allegation, saying: "I have hired professional personnel to work at the village."

To increase the level of trust in charities, many experts argue they should be made independent of government departments.

"Charity should be independent from authority, while transparency should be realized through social supervision, not regulations," said Deng, who added that many of the problems charitable NGOs face are caused by the complex registration process.

"The easiest way (to boost the sector and ensure transparency) is to allow more room for these organizations to register. Only by doing this can more charities get the chance to impact society."