Society

Students' way to schools turned into journey of perils

By He Na (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-07-01 07:50

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

The only difference was that no one was laughing.

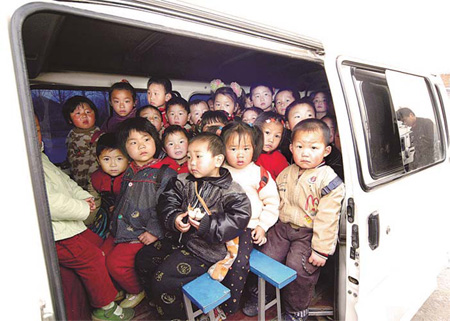

When police pulled over the 4-meter-long coach on June 12 in downtown Panjin, a city in Liaoning province, they found it literally full of primary school and kindergarten students.

Four or five children were sharing one seat, while others were sprawled across their classmates' laps.

"Many of them had to sit with their faces pressed firmly against the window," said Hou, an officer with the city's traffic division. "There would have been a catastrophe if this bus had even a minor accident."

Wang Qiangqiang, 7, had been crammed into the front passenger seat with four other boys. "It was so hot," he said. "I found it hard to breathe with two others sitting on my legs. They were so heavy."

Hou said the case was the worst example of cramped conditions on buses that he and his colleagues had seen for a long time. A subsequent investigation found the vehicle, which was labeled one side with "Hope Kindergarten", was not even put through the annual check required under the Law on Road Traffic Safety.

The driver, who was hired by the school, was later fined 2,000 yuan ($290) and had his license revoked.

Thanks to Panjin traffic police, children on the Hope Kindergarten bus escaped a potential disaster. Others have not been so lucky.

On June 4, an illegal minivan taking more than 10 students to school flipped over on a road in Bishan county, Chongqing. One youngster died, while the others were left with serious injuries.

Just one month earlier, a girl surnamed Chen was also killed in downtown Chongqing when a bus carrying 12 children careened off the road.

More than 46,454 road traffic accidents occurred during the first three months of this year, killing 13,289 people and injuring more than 55,000, according to figures from the Ministry of Public Security. Crashes involving school buses, however, make up a worrying proportion of that statistic, with such incidents increasing 8.2 percent over the same period last year.

The figures show that 4,423 students died and 20,917 were injured in traffic accidents in 2008, with most involving vehicles transporting children to or from school.

In an effort to tackle the worsening trend, traffic police in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, launched a clampdown on unsafe coaches at the end of April. Within a day, officers found that just more than one-third of the city's 3,450 registered school buses were unfit for driving on the road.

"Shenzhen is considered to be one of the most developed cities in China but the situation there is still grave," said Yuan Guilin, a professor at Beijing Normal University who has studied school bus safety for more than five years.

"The number (of unsafe buses) is probably much higher as there are so many unregistered school buses," he said.

Ministry of Public Security officials attempted to address the poor management of school buses and the growing number of accidents in 2006 through a nationwide campaign. However, four years on, the problems remain a real danger to China's children.

|

|

"School bus safety affects thousands of families," said Yuan. "But even though it is one of the most important factors in the development of education in China, the issue is being neglected."

Although the blame lies firmly with irresponsible drivers and the administrative departments that are failing to guard against overcrowding and poor standards on school transport, "the key point is the issue of who actually owns the bus", he said.

Li Luxin, deputy secretary-general of China Youth and Children Research Association, agreed and said that efforts by some education departments to farm out school bus runs to individuals or private companies have only made things worse.

"In a few cases, government departments invest only a small proportion of the running capital, while most comes from the families of students who use the buses," he said, adding that when profits are involved, overcrowding, high prices and lower quality service are inevitable.

"Some schools choose to manage the bus runs on their own but they need strong financial support," he explained. "Although some charity organizations and funds donate money to schools, once the support from the government and others stops, few can afford the maintenance costs."

In some areas, parents pay private vehicle owners to transport their children "but this too has huge safety risks and it can be hard to get compensation after accidents," added Li.

Experts are now calling for the governments to foot the bill by setting up a system that would allow school buses to be part of well-regulated and integrated public transportation networks.

In some countries, like the United States, special laws set clear terms guaranteeing the standards of school buses. Yet China has none - even in the Law on Road Traffic Safety - meaning that the nation is sorely lacking in a firm management and supervision system, said Yuan.

"Some local governments have set rules to make school buses uniform, such as demanding they all be painted the same color, but these are rarely compulsory measures," said the professor. "It's time China worked out a law just on school bus management, which will ensure officials to change their attitude from passive management to active supervision."

Rural struggle

A pilot program that will offer free school transportation is to be launched in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, this year and will cover not just urban areas, but also villages on the outskirts and further into the countryside.

"If the experiment goes well, it could be spread to more cities," added Yuan.

School buses operating in rural areas are arguably the most in need of greater supervision.

Analysis carried out by Yuan and his students on 74 school bus accidents over the last five years showed almost 75 percent of the victims were rural children - 49 percent primary and middle school pupils and 50 percent kindergarten.

"When we did the research in the countryside of provinces like Yunnan, Henan and Jilin, we often saw a dozen or so children standing on the back of tractors or crammed into minivans," said the Beijing professor. "We also saw people using tricycles, four-wheeled farm vehicles and even scrapped cars to transport students."

Unlike in many urban areas, students in rural areas often have to travel many kilometers from their village to get to class every day. Although some schools provide dormitory beds for pupils, not all village families can afford the fees, while the accommodation itself can be poor.

"It means these families have no choice but to rely on low-quality vehicles to solve the transportation problem," said Yuan. According to a study by Huazhong Normal University in Wuhan, Hubei province, the long distances that rural students must travel has now surpassed poverty and study difficulties as the No 1 reason why village children drop out of school.

As other countries have proven, the best solution is either to improve school transportation services or school accommodation. The former is likely to be the cheaper and more flexible option.

"Rural schools need to focus on two aspects," said Yuan. "The government needs to update the conditions in school dormitories and hire more management staff and teachers.

"Meanwhile, free buses need to be introduced in the countryside as soon as possible."