Society

The American dream of the Chinese rich

By Duan Yan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-06 08:23

|

Large Medium Small |

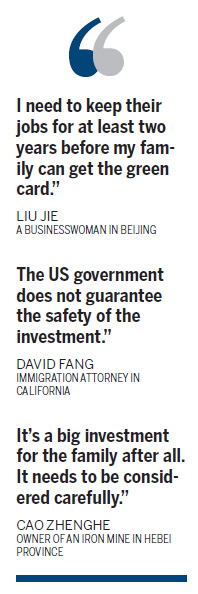

The first to notice the surge of Chinese applicants for investor green cards was the lawyers who specialize in visa applications. At his law office in City of Industry, California, immigration attorney David Fang took his first investment immigration case for a client from Taiwan when the program was authorized in 1992.

At that time, the investment was $1 million. Now the minimum is $500,000.

Ten years ago, 70 percent of his clients were from Taiwan and the rest were from Hong Kong. "Now, 70 percent of them are from the Chinese mainland," Fang said.

The US life

Adjusting to life in the US does not seem to be a problem for Lily Zhang and her husband, who can read and converse in basic English. "You don't need that much English for daily life," she said. And as for the business, she has hired a translator to help.

Now more than 1.1 million Chinese Americans live in California, according to the US Census Bureau's 2008 American Community Survey.

At her law office in Chinatown, New York, Yang Fuhao has seen a decline in H-1B work visa applications from Chinese, but has received more inquiries about investor visas. New to the business of investment immigration, she is now representing three clients in that capacity. "All of them are from the Chinese mainland," Yang said.

Contrary to the new boom in investment immigration for the Chinese mainlanders, many Chinese graduates of US universities faced difficulties finding a job in the US, and many decided to go back to China. The number of H-1B work visas for Chinese citizens dropped from 16,628 in fiscal year 2007 to 12,922 in fiscal year 2009, according to statistics from the US Department of Homeland Security.

For Zhang, that's exactly one of the reasons that she invested in the US for her daughter Yvonne. During the economic downturn, a green card for her daughter will make sure that she won't face the same job-hunting difficulties many of her classmates and friends faced.

"You just don't know what will happen to the immigration law if and when a new president is elected. And all the good jobs are saved for US citizens and green card holders," Zhang said.

Less pressure

Yvonne Liu is studying economics and business management at the University of Missouri at Columbia, and will graduate next summer. She liked her studies in the US because she has less pressure there.

"No one will keep their eyes on me or give me too much pressure. I can do whatever I want," she said.

She joined a popular music band in school with some of her friends. "And I don't need to worry about my parents when they grow old because the social welfare system here is better. "

She doesn't have to compete with more than 9 million Chinese students in the national college entrance exam.

"The US college application process is more personalized," she said.

Liu appreciates what her parents have done for her.

"Many of my (Chinese) friends in school wanted to stay in the United States, but there are many difficulties. I'm really lucky that I don't have the same worries because my parents are very capable."

Selling the program

In Beijing, wealthy parents like Cao Zhenghe went to information sessions and promotions for US investor immigration programs, looking for opportunities that can help their children have a better future in the United States.

"Are you also here for your kid?" Cao asked a middle-aged woman who sat next to him during an information session. She nodded yes. During two days of information sessions for investment immigration projects, Cao met several parents who had already sent their children to study in the United States.

"We don't chat a lot with each other, you know, because of privacy concerns," Cao said.

For many wealthy Chinese, investing $500,000 into a US government designated regional center program is one of the most convenient ways to reach their American dream, or for their kids.

Cao, 45, came to Beijing on June 10 and went to a session hosted by Beijing Worldway Immigration Service Co, to learn about a regional center program about a gold mine in Idaho. He flipped through the brochure and jotted down notes and questions as immigration consultants and representatives from regional centers continued to sell him on the project.

Although he was told that his money will be safe and he can buy out his investment after five years, Cao knows that many of these projects bear a certain risk. He is finding it difficult to choose the right one. "I'm getting tired of these meetings now," Cao said.